Beyond a request to attend the Arangetram, what do these invitations tell us?

Introduction

Power of paper and a few words

The power of paper and a few words is immense in being able to illuminate the social and cultural aspects of a time bygone. Quite contradictory, but you read that right! Ephemera, such as posters, tickets, invitations, brochures, etc. are an important source through which the readers becomes an audience—it enables them to visualize a performance again. Moreover, ephemera transports the reader into “the experience of those […] who once tasted those intensities, and for whom those moments were the warp and weft of their deepest personal and collective selves.” (Schofield, 1).

The term ‘ephemera’ is derived from the Greek word, ‘ephemeros’ meaning, ‘lasting only a day’. During the sixteenth century, it was used in the context of plants or insects that had a short life span but now it denotes a subculture within print media that is intended for a glance by the reader.

Sunil Kothari and his Collection

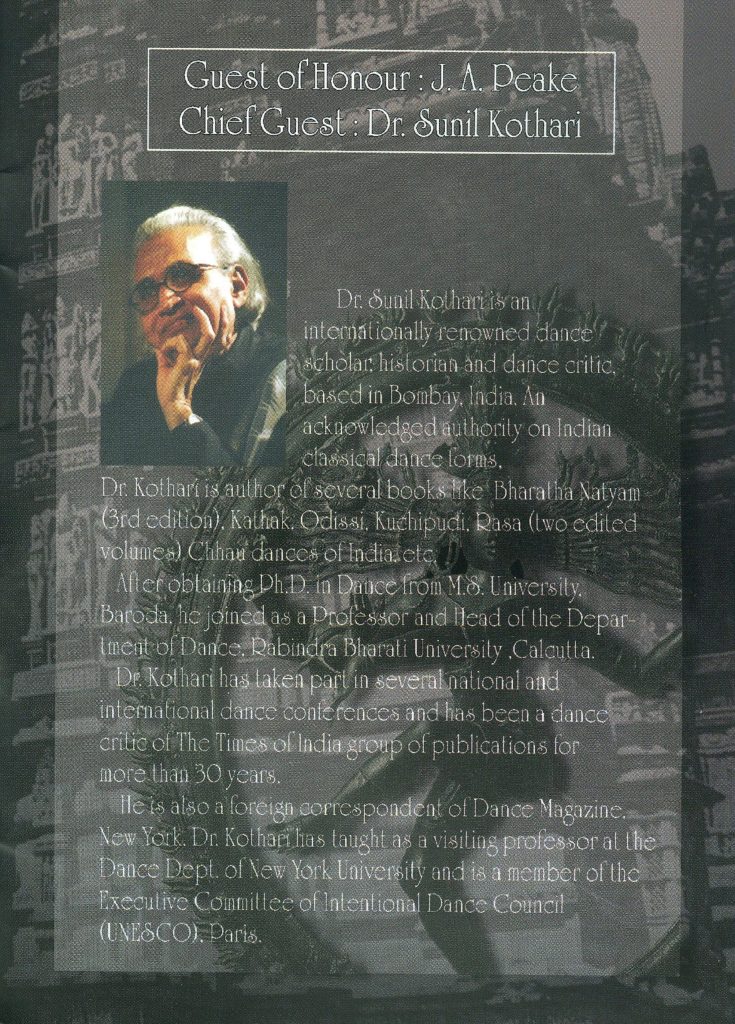

Ephemera, as a category in the archive is born out of a collector’s lifelong passion about a subject. One such person was Sunil Kothari, whose practice of saving everything from seemingly trivial pieces of paper to important documents is now a gift to the field of Dance Studies in India. Kothari was a well-known critic and a scholar of dance.

One of the limitations of any collection is that it only reflects the collector and their field of interests. Therefore, this exhibit, in no way attempts to generalize the theme of Arangetram in Bharatnatyam. Rather, it should be seen as an analysis of a collection, by a particular collector.

This digital exhibition, Eternalizing the Ephemeral, is based on the Performing Arts Ephemera Collection of Sunil Kothari housed at the American Institute of Indian Studies’ Archives and Research Center for Ethnomusicology (ARCE), in Gurugram, India. In addition to Ephemera, the Sunil Kothari Collection at ARCE includes photographs, manuscripts, documents, correspondence, books, and recordings.

The Performing Arts Ephemera Collection of Sunil Kothari has over 4,000 documents in total, neatly categorized in folders covering genres like, Bharatnatyam, Kathak, Kuchipudi, Odissi, and more. This collection also contains folders on individual figures from the performing arts such as, Chandralekha and Uday Shankar to name a few. Interestingly, this collection also has folders named after the collector himself, containing over 250 documents in total.

The folders have been created not using standard classification systems but creating categories which may be relevant for research.

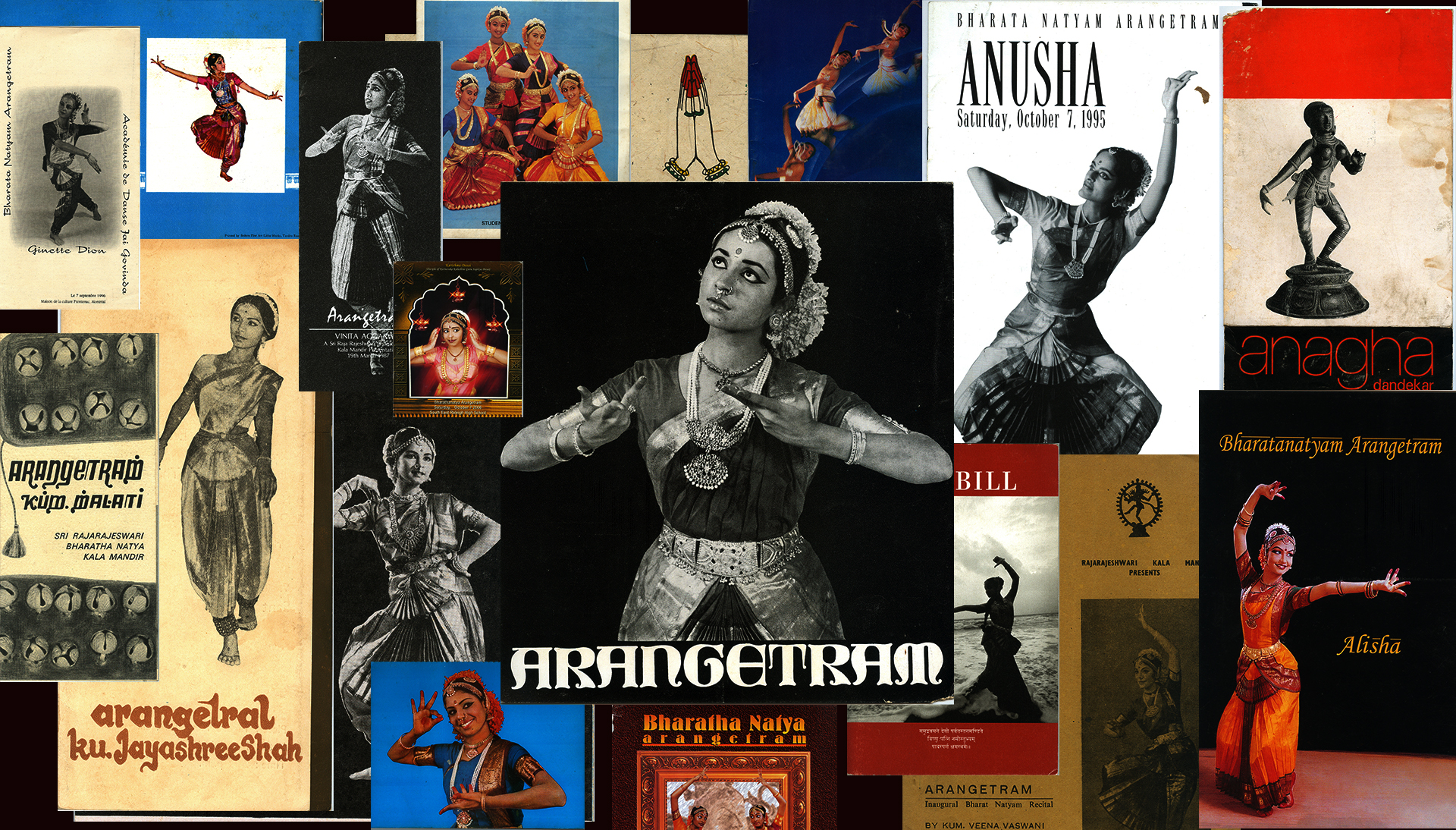

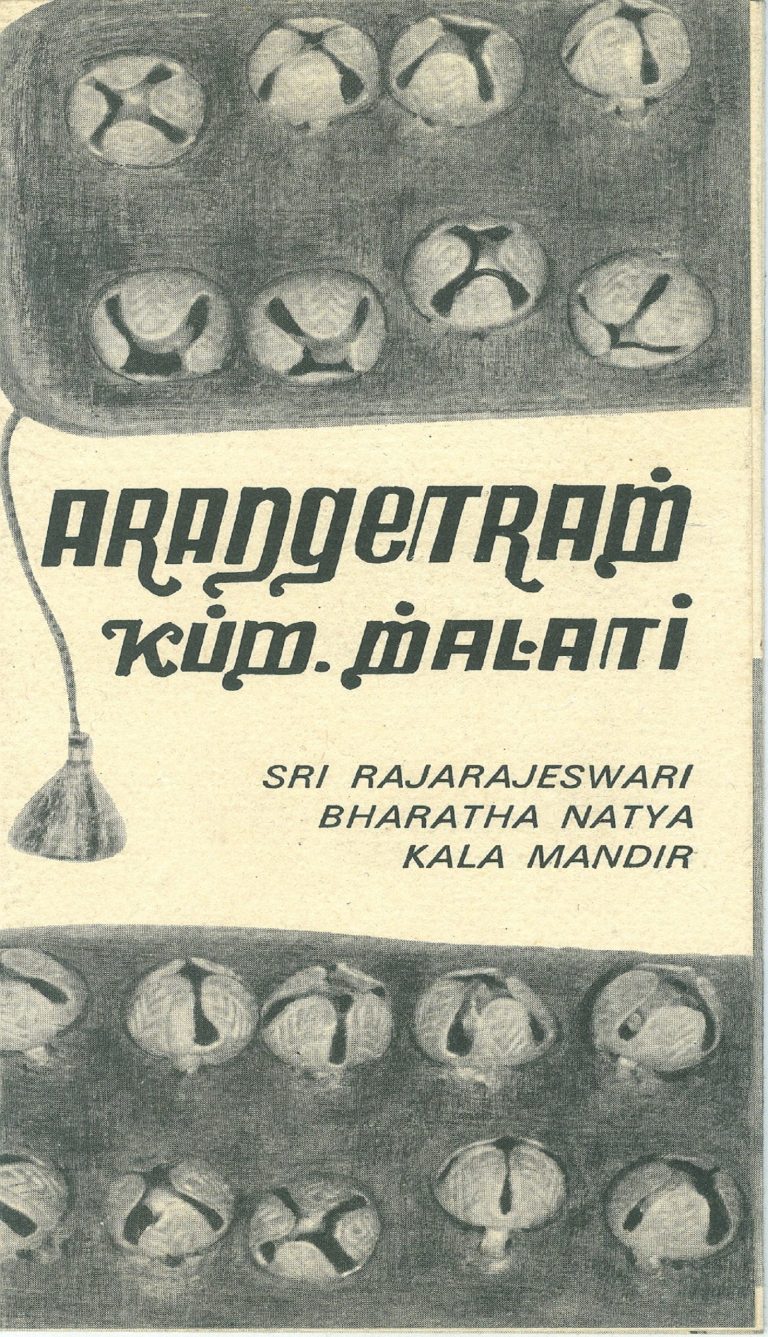

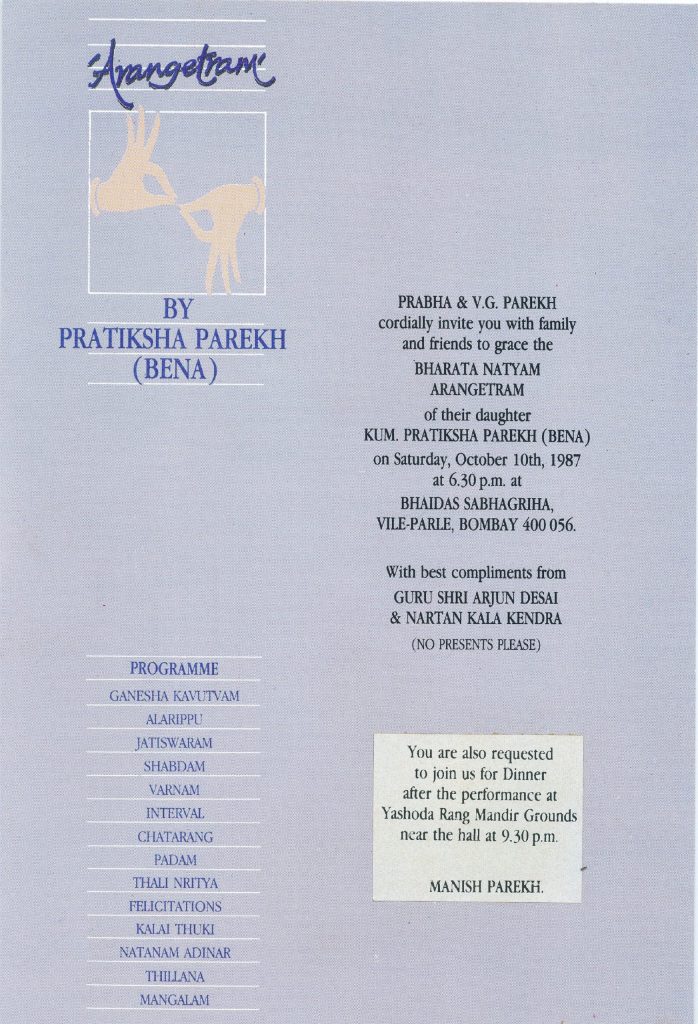

‘Arangetram’ appears as a separate category in the collection though being related to the classical dance form of Bharatnatyam, because of its potential as an area of research. The Arangetram folder contains principally invitations from India and abroad.

Arangetram as a Rite of Passage

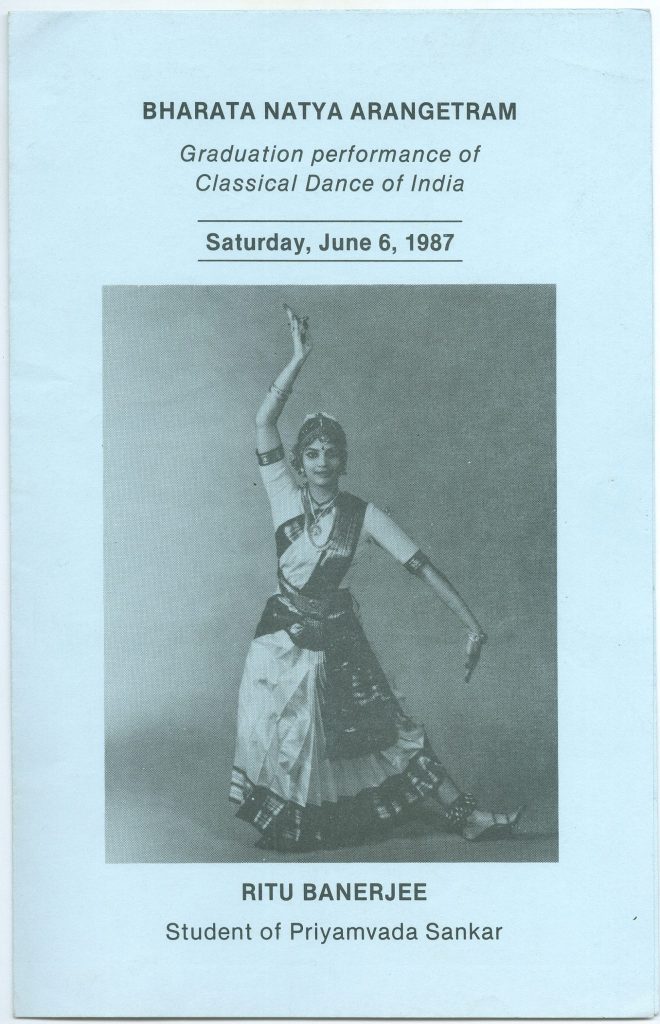

Believed to be about 2000 years old, Bharatnatyam is perhaps today one of the most iconic classical dance traditions in the world. Arangetram literally means, ascending the stage and signifies a moment of transference from being a student to a professional dancer after years of rigorous Bharatnatyam training. The focus of this exhibition is on Arangetram, a ritual performance, wherein the teacher presents her student in a public ceremony, who is now accomplished to perform independently.

This exhibition takes you through the corporeal remnants of these debut dance performances through an analysis of Arangetram invitations. We see how they help us in understanding the role of Arangetram in Bharatnatyam and society at large through a variety of lenses. These invitations enlighten us about the trajectories of several dance teachers and the dance schools that are otherwise difficult to find in libraries. So, they prove an important sources to access information about the Bharatnatyam dance form from years which are now lost to time.

The Arangetram invitations were sorted by me into two categories: India and the Indian Diasporic Community. This decision was made to highlight not only the special characteristics but also to point to the similarities between invitations from different geographies. There were a large numbers of invitations from diasporic communities which reflect Kothari’s connection not just with India but also with overseas communities.

o Total Arangetram invitations from Indian cities – 53

Mumbai – 22

Chennai – 10

Ahmedabad – 7

Bengaluru – 8

New Delhi – 5

Assam – 2

Baroda, Hyderabad, Tiruvanmiyur, Tiruchirappalli, and Chidambaram – 1 (each).

The Indian city-wise distribution tells us how much Bharatnatyam has moved out of Tamil Nadu, where it originated. It also reflects on the network of the collector, Sunil Kothari. He was born in Mumbai and lived there for the most of his life–which explains why Mumbai has the highest count of invitations. He was also well connected within Gujarati artistic and literary circles that supports the presence of Ahmedabad in his collection.

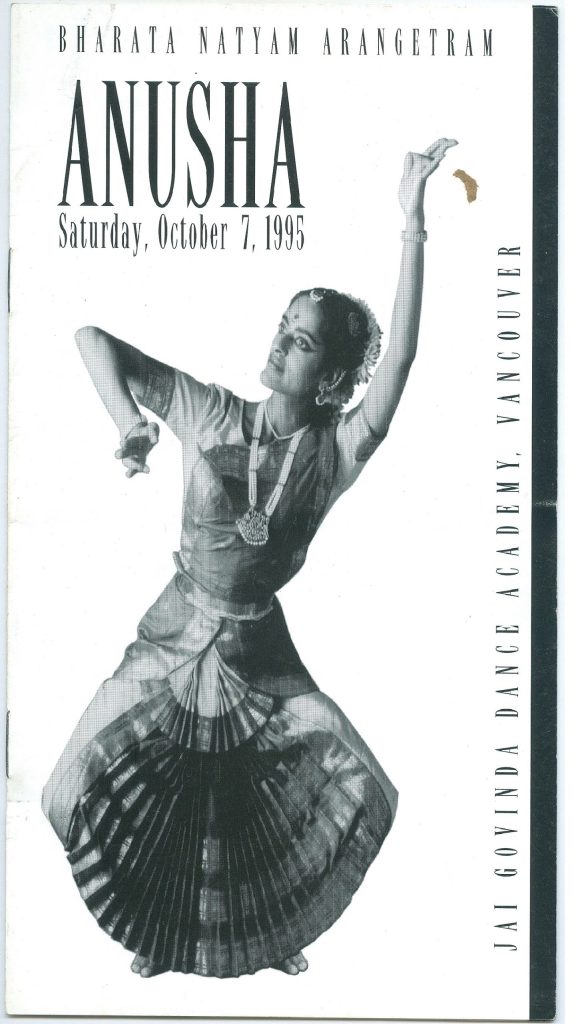

o Total Arangetram invitations from the Indian diasporic community – 24

Canada and USA – 10 (each)

South Africa – 5

United Kingdom – 3,

Kenya – 2

Malaysia – 1

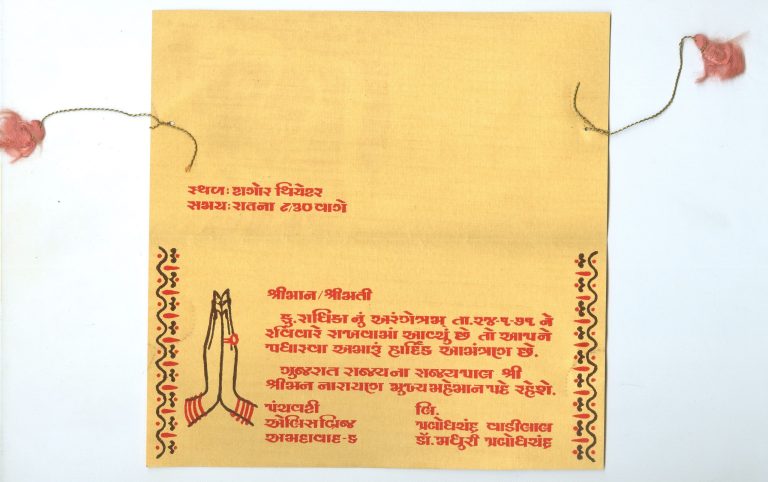

What is intriguing about these invitations is that besides English, languages like Sanskrit, Gujarati, Kannada, Tamil and even French have been used.

A note on exhibition concept

Beyond a request to attend the ceremony, what do these Arangetram invitations tell us?

This exhibition attempts to analyze Arangetram invitations from the year 1960 to 2019, from both India and abroad. The intention is to understand how the key players involved in an Arangetram ceremony i.e. the dancer, the teacher, and the parents wanted themselves to be presented to the world–and why. This is done through an exploration of social and cultural themes such as, the Teacher-Disciple Tradition (guru-shishya parampara), social capital of the dancer, and the degree to which theoretical information is incorporated in an invitation.

This exhibition also intends to analyse the imagery and rhetoric used in the Arangetram invitations to understand how the dancer was presented to the world. Beyond all this, Arangetram invitations also acted as souvenirs to be kept as keepsakes by the teacher, parents, and important from our exhibition’s perspective– the collectors. Arangetram invitations, thus, become a crucial site of enquiry which offer us a glimpse of how the dance composition would have looked like—on paper.

Garnering Authenticity

Guru of Guru of Guru of Guru (Guru-Shishya Parampara)

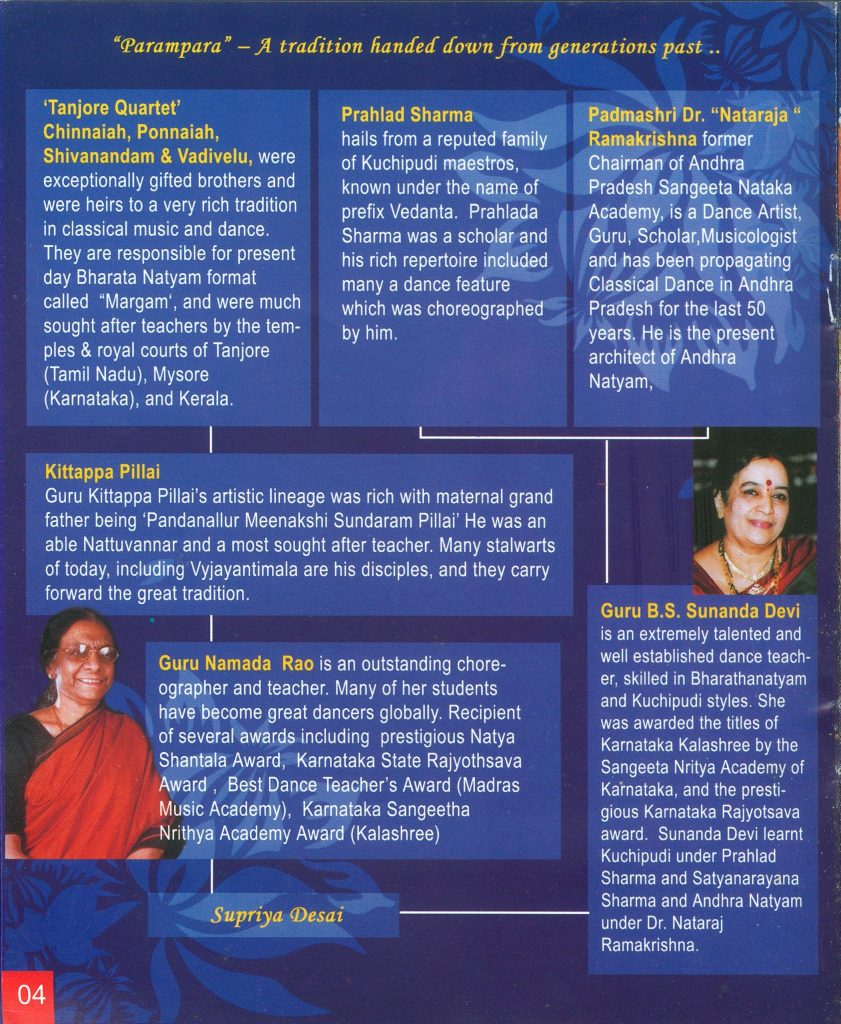

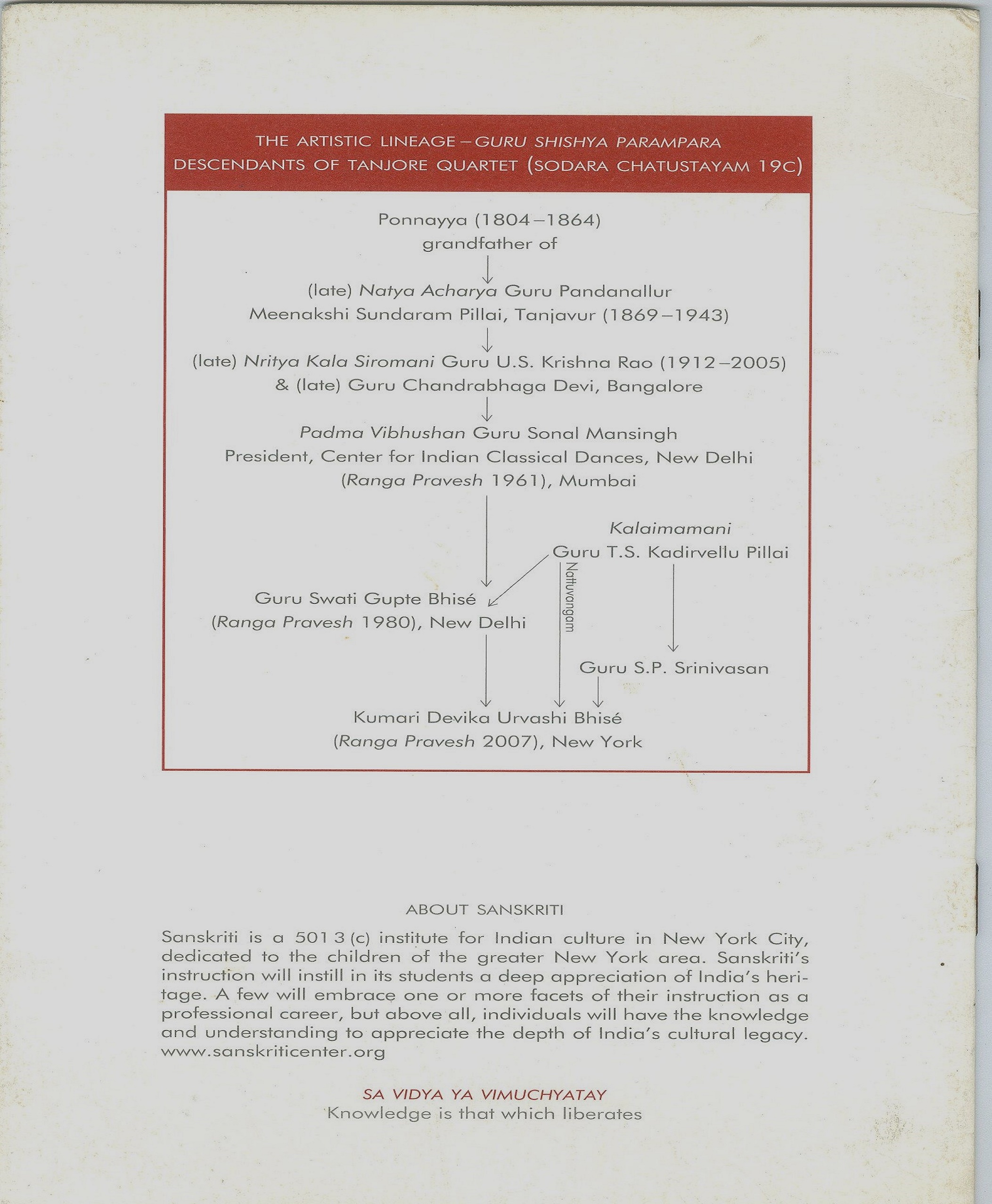

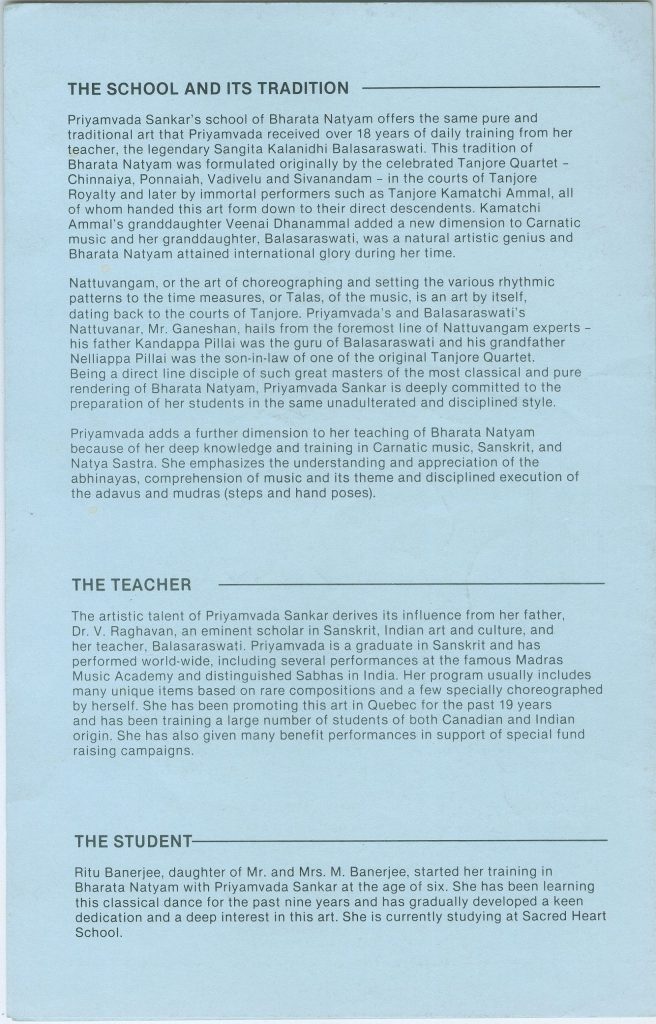

The guru-shishya parampara or the tradition of teacher-disciple, connects the guru to their previous generation of gurus–much like any geneology. But more practically speaking, it involves passing down of skills and knowledge about the dance form and tradition from the teacher to student. Lineage-tracing is one of the prominent elements of Arangetram invitations from India but more so in invitations from abroad. It presents the teacher as the rightful and authentic offshoot of the larger Bharatnatyam tradition of dance.

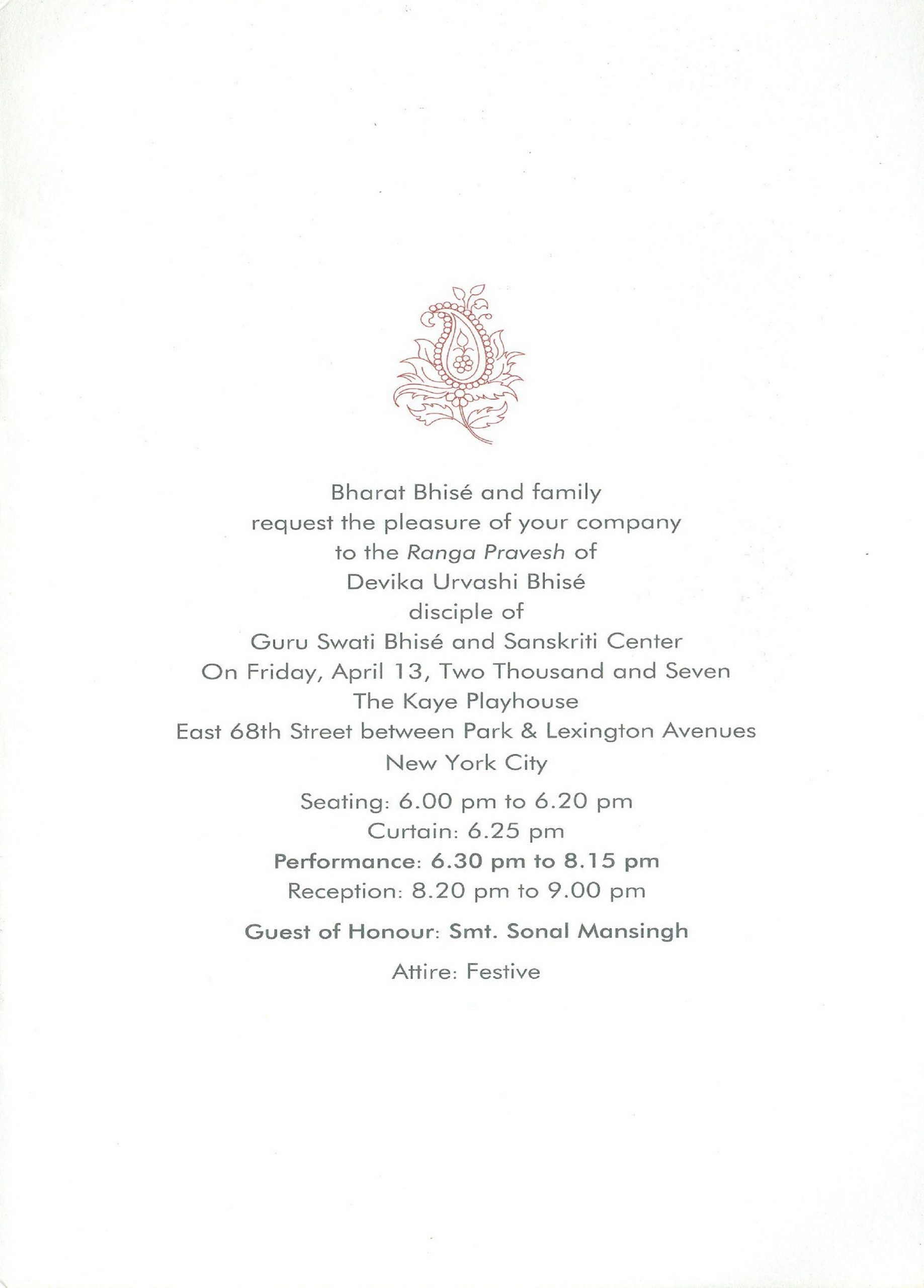

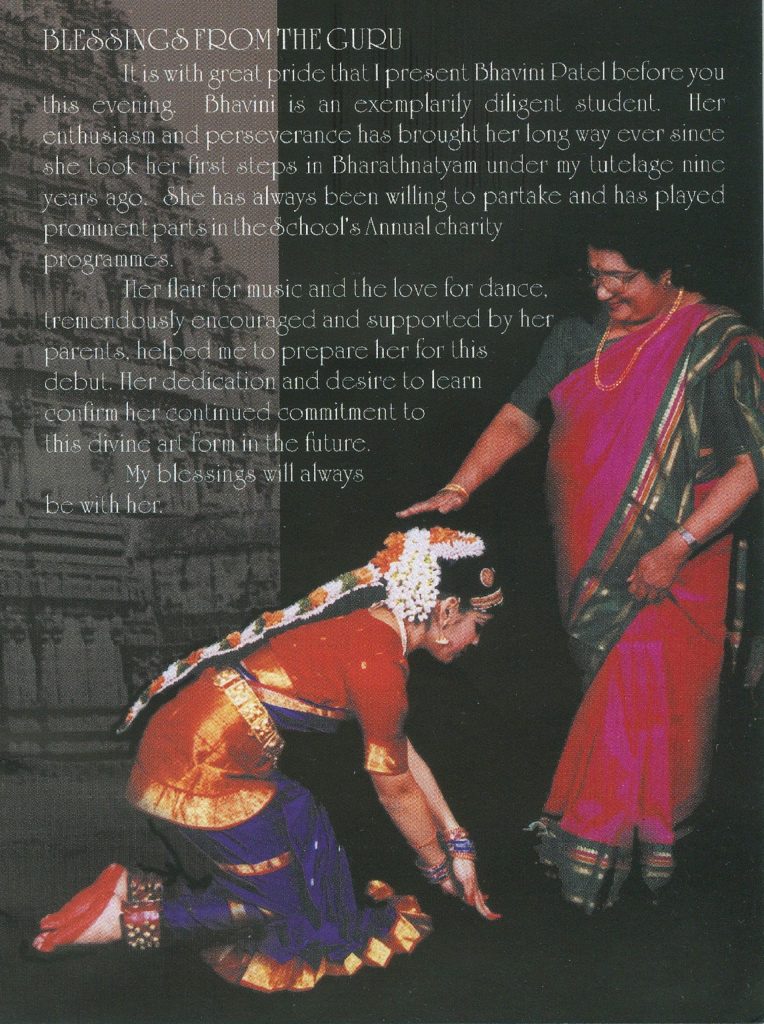

A glace at the Indian diasporic community’s Arangetram invitations shows that they trace the teacher’s lineage as further back as possible until it reaches an established Indian guru. This is done to bridge the ‘faraway-ness’ of the debutant student to their homeland, India. Moreover, it enables the gurus of diasporic communities to present an Indian classical dance, in a non-Indian distant land with credibility and autheticity. Describing a lineage links the guru to the heritage of ‘pure’ or authentic style of Bharatnatyam. A large number of Arangetram invitations reveal that dance schools and institutions organize these ceremonies and promote the institutions. The linkages of the school and the teacher benefit the dancer who is being launched. In fact, occasionally the focus in the Arangetram invitation is so much more on the teacher that the dancer whose Arangetram it is, receives a passing mention. As illustrated in the example below:

But there are exceptions too. For instance, this invitation from Ahmedabad, India, of a dancer named Radhika (see below) mentions neither the teacher nor the school–one wonders why?

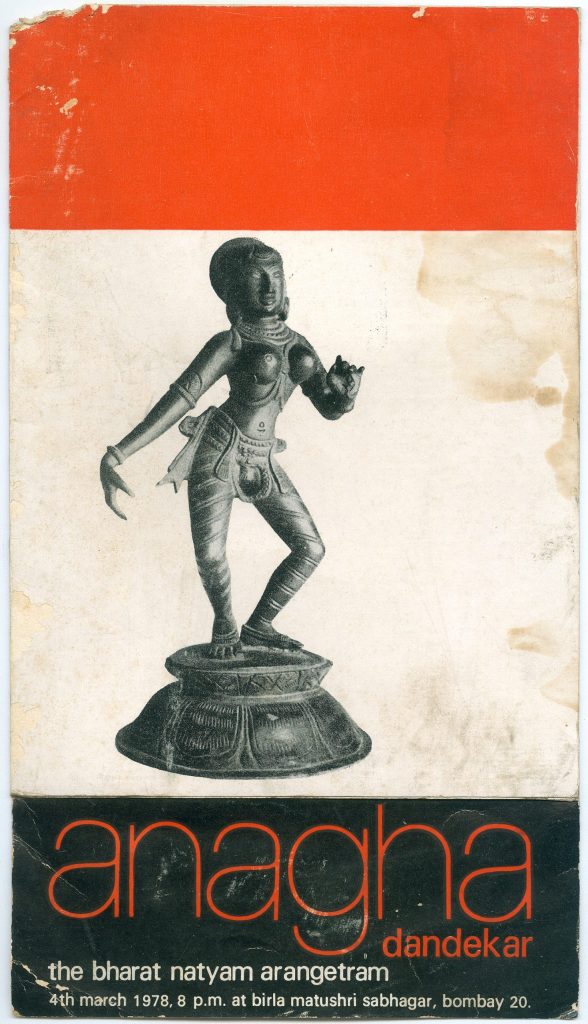

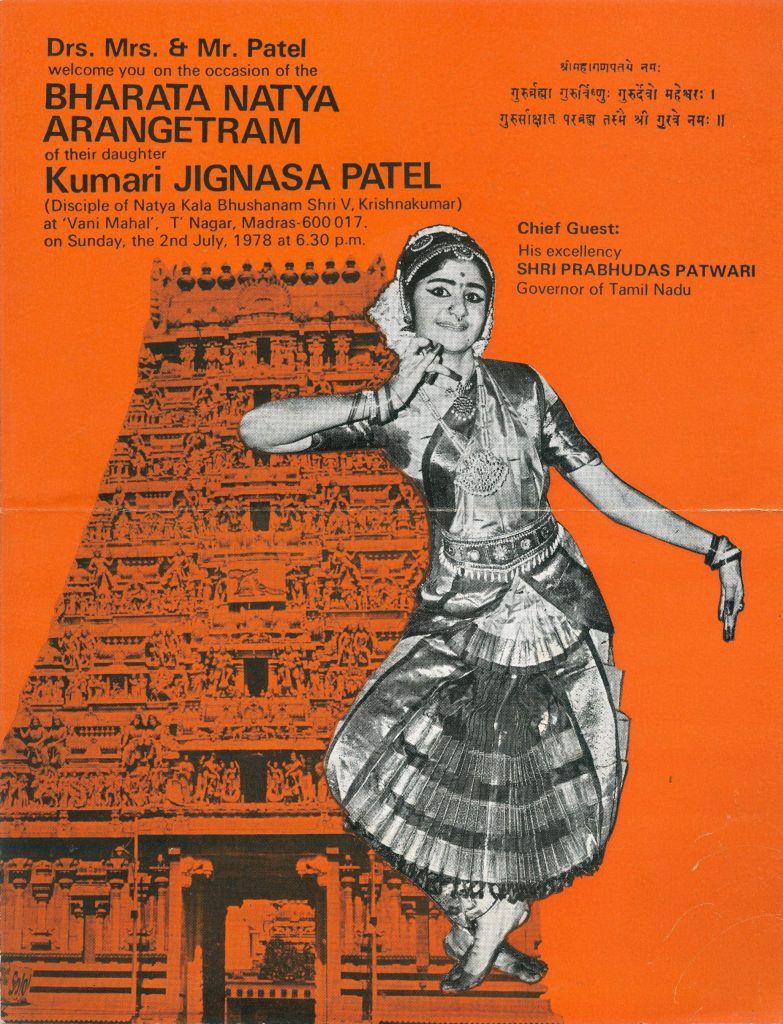

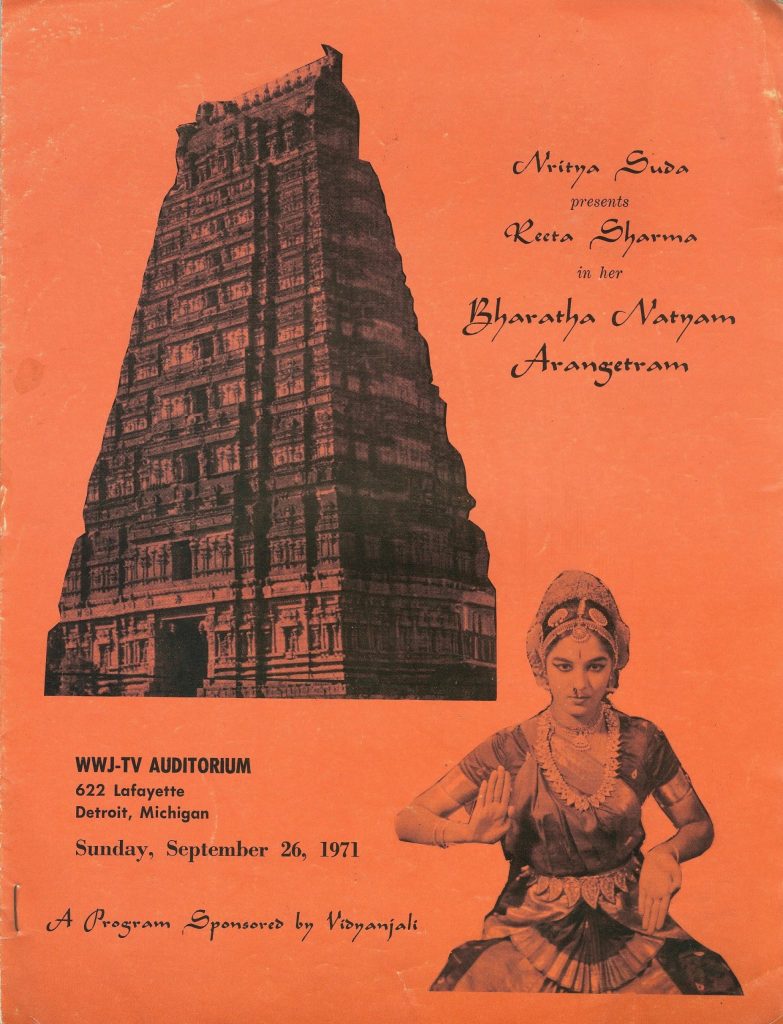

Temple Imagery – a link to the past

Arangetram invitations, both in India and in the Indian diasporic community, make an effort to link to the 2000-year old tradition of Bharatnatyam with their present. One of the ways of doing this is through imagery. A common way of evoking the historical links of Bharatnatyam is through temples on the cover of Arangetram invitations. The origins of Bharatnatyam with temples are well established.

Therefore, by using the temple imagery in their Arangetram invitations, the dancer, irrespective of the geography, try to place a claim in this long rich history of Bharatnatyam.

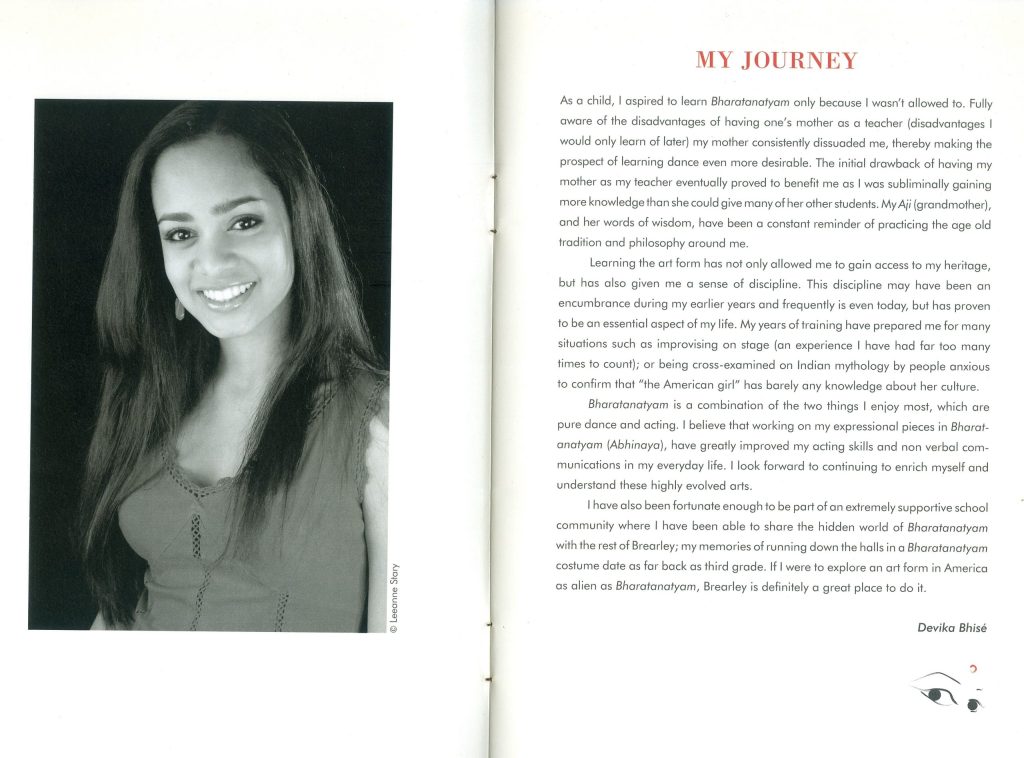

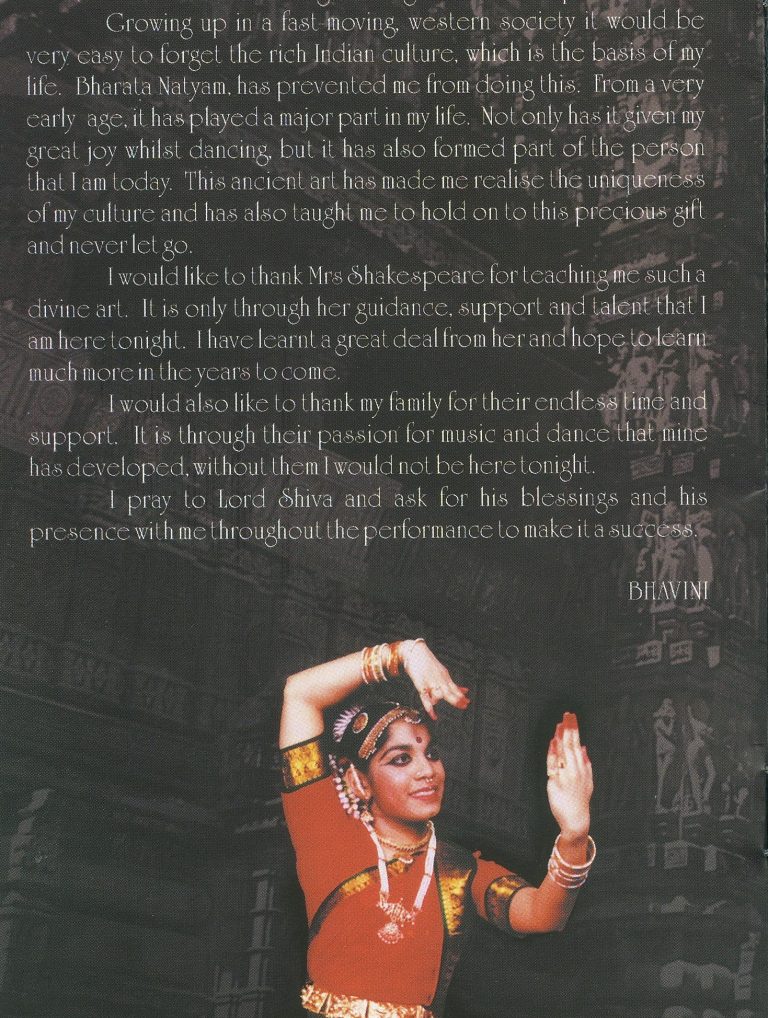

Indian Enough?

One of the ways of garnering authenticity in Arangetram invitations by the Indian diasporic community is the use of rhetoric in dancer biographies. For example, the recurring use of words and phrases like “eastern roots”, “devotion”, “understanding Indian culture”, “access to heritage” establishes links between the dancer and their Indian background. Thus, the rhetoric used in dancer profiles evoke a sense of home or connection with it, which aids the display of authenticity in a faraway land.

Social Profile of a Dancer

Arangetram is an equally important affair for the debutant’s parents as well. Ostentatious expenses on a live “orchestra”, costume and jewelry, production, glossy invitations, refreshments and lavish dinners, and sometimes even a week-long program in a different city; all add to the cost of organizing an Arangetram. The expenses are borne by the parents–both in India and abroad.

What is in a Name?: Influence of the Family and Dancer

However, beyond ostentatious displays, social influence acquired over years and even generations help raise the status of the Arangetram. This exclusive social capital includes connection with influential figures from different fields.

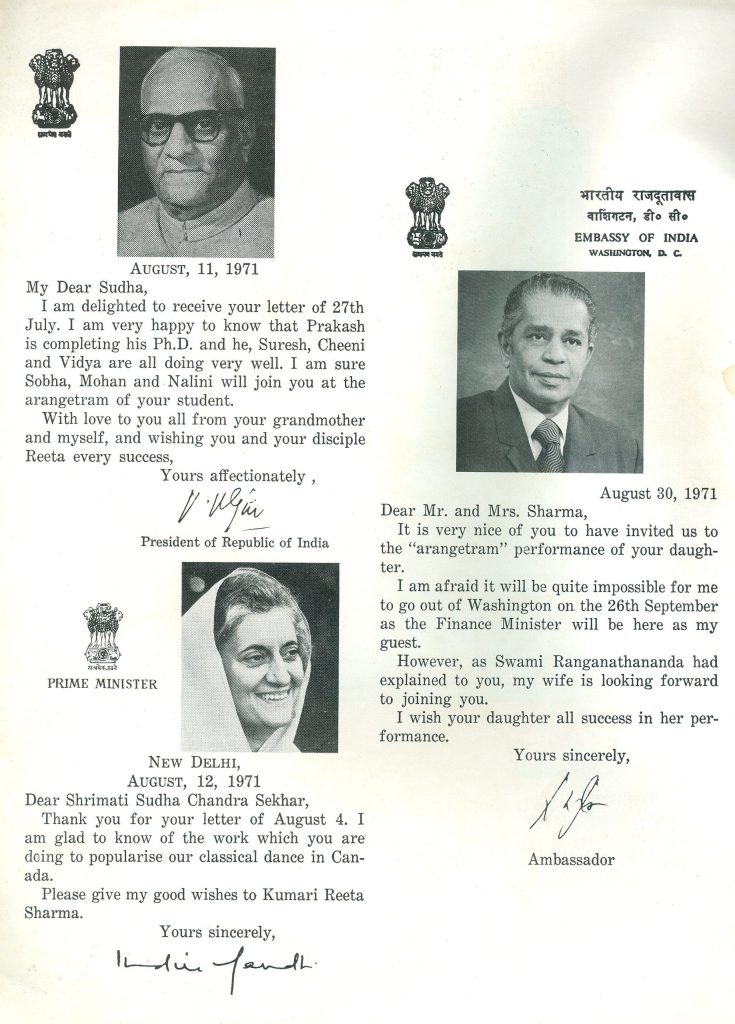

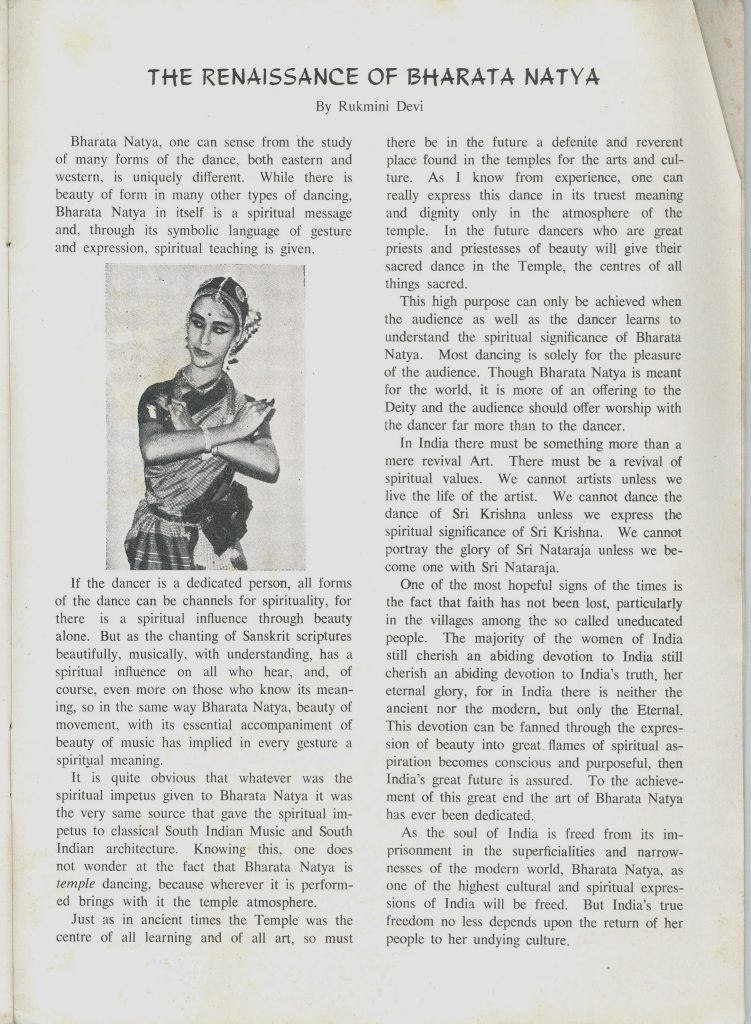

For instance, inclusion of letters of support from political figures like, the former Prime Minister of India, Smt. Indira Gandhi, former President of India, Varahagiri Venkata Giri add to the influence of family in society. Furthermore, inviting renowned Bharatnatyam dancers like, Rukmini Devi Arundale and Sonal Mansingh add to the prestige and artistic standing of the dancer and their teacher. Lastly, the presence of a dance critic like Sunil Kothari gives gravitas to the dancer; and his review after the ceremony, raises the profile of the dancer in the Indian performing arts scene.

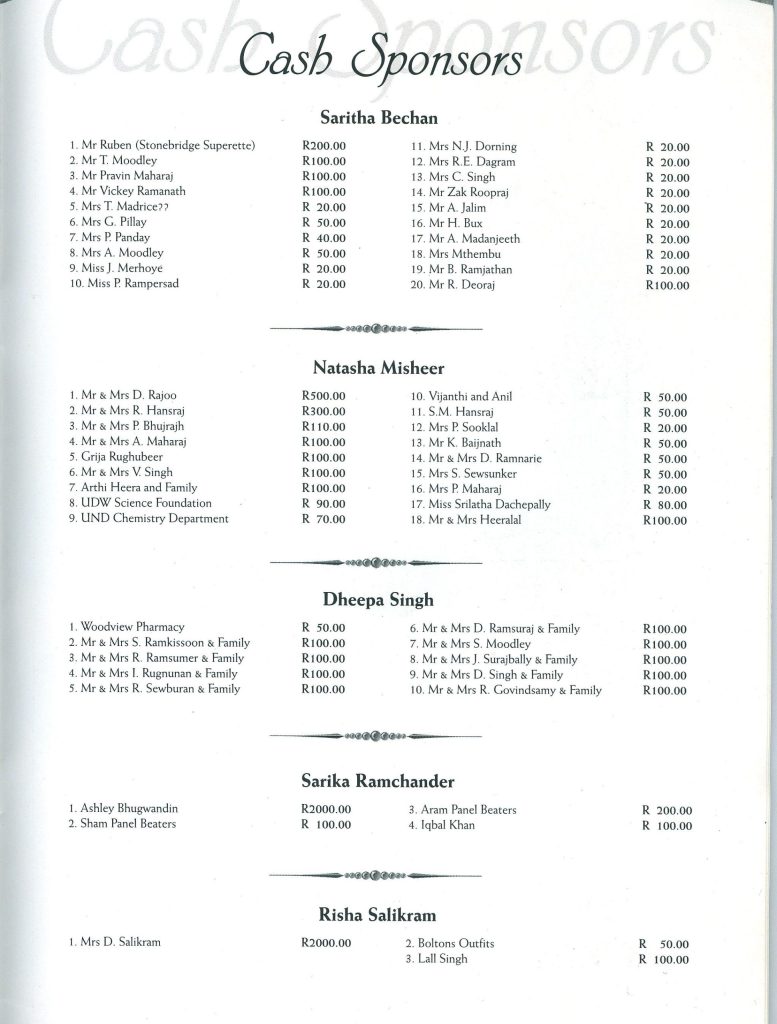

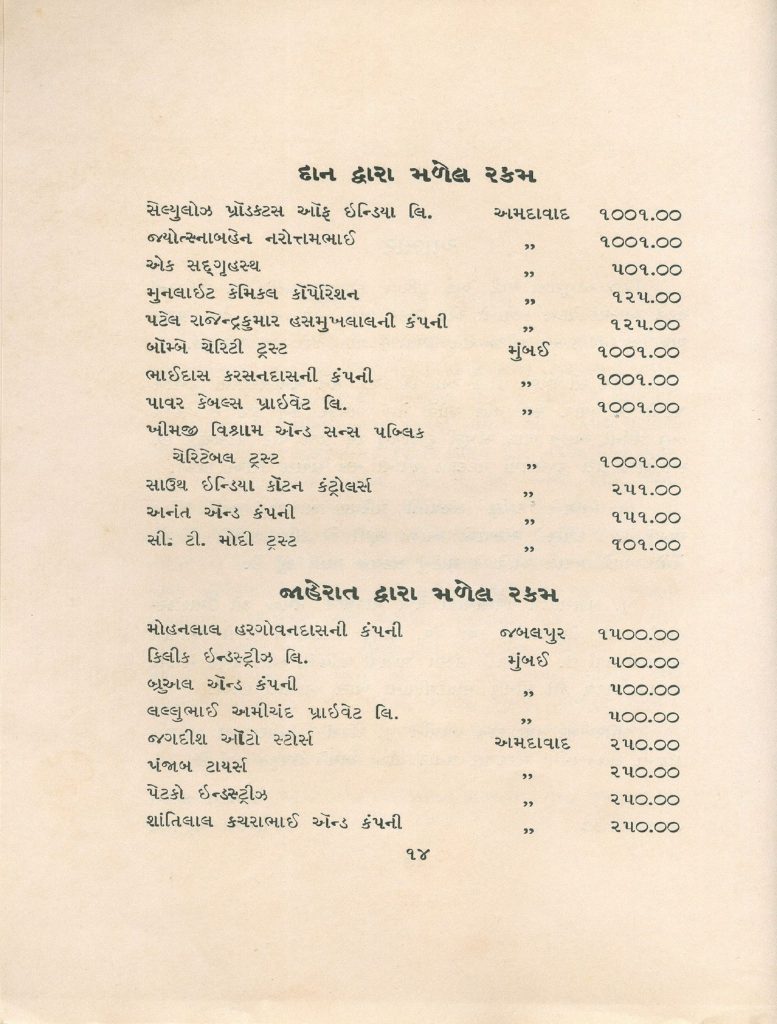

Arangetram and Financial Support

Donations:

Organizing a successful Arangetram needs financial support. Thus, securing sponsorship in the form of direct support through donation (dan) from family, friends, and sometimes anonymous “well-wishers” shows the families’ social connections and influence. So much so that, this sponsorship is publicly acknowledged in the Arangetram invitations, as seen in interesting documents below.

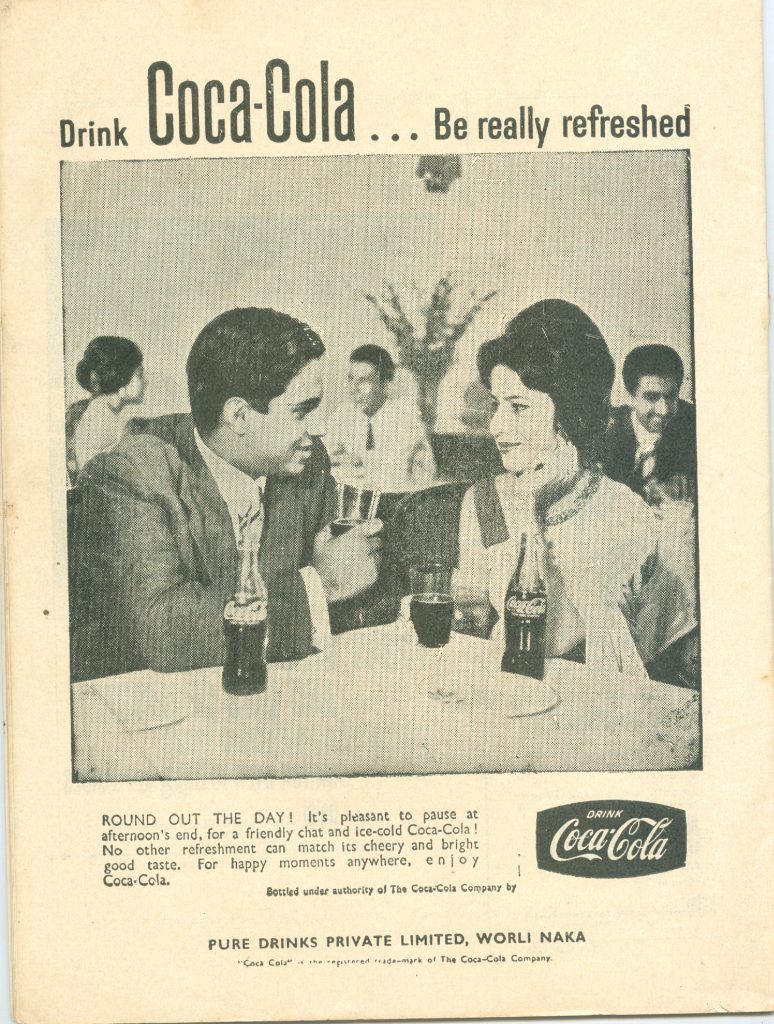

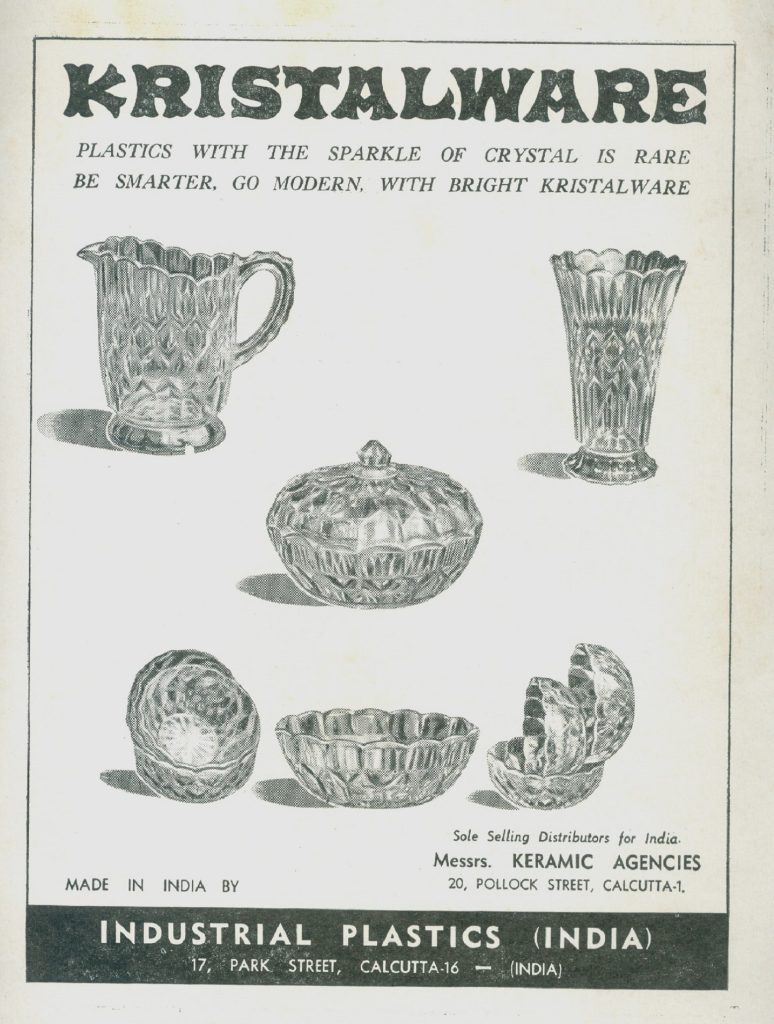

Advertisements:

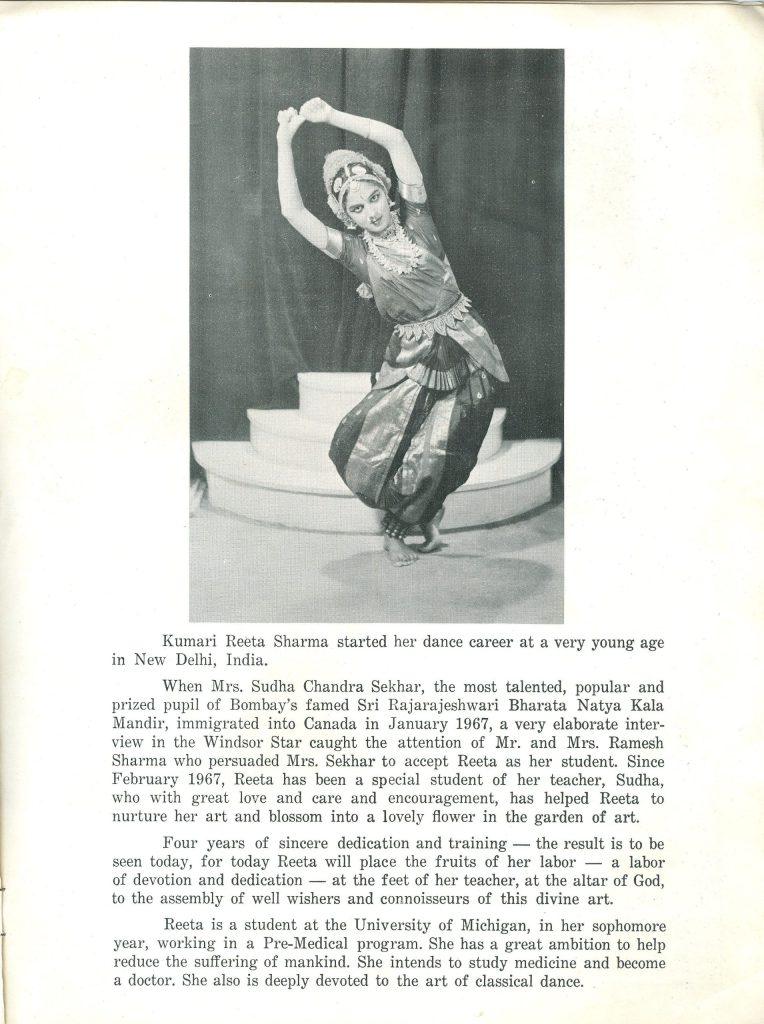

This is one of the most interesting elements of Arangetram invitations. Another way of securing financial support for the ceremony is through advertisements. Sometimes, the numbers are so high that more than half of the invitation booklet is filled with advertisements instead of information on Arangetram. The advertisements range from cold drink brands like Coca-Cola (India) and Coo-ee (South Africa) to cigarettes like Panama and Wills (India). Advertisement of diasporic South Asian community’s ladies boutique also feature in Arangetram invitations.

Dancer or a Social Actor?

The Indian diasporic community’s Arangetram invitations weave the dancer’s social profile with a constant emphasis on their performances for the social causes. The dancer’s and teacher’s profiles in Arangetram invitations find mention of performances done for charities, relief funds, environmental causes, and so forth. This is occasionally found in Indian Arangetram invitations as well but there is a sizeable occurrence in the ones from abroad. This is done to project a socially-conscious being who understands the social responsibility of Art beyond the stage.

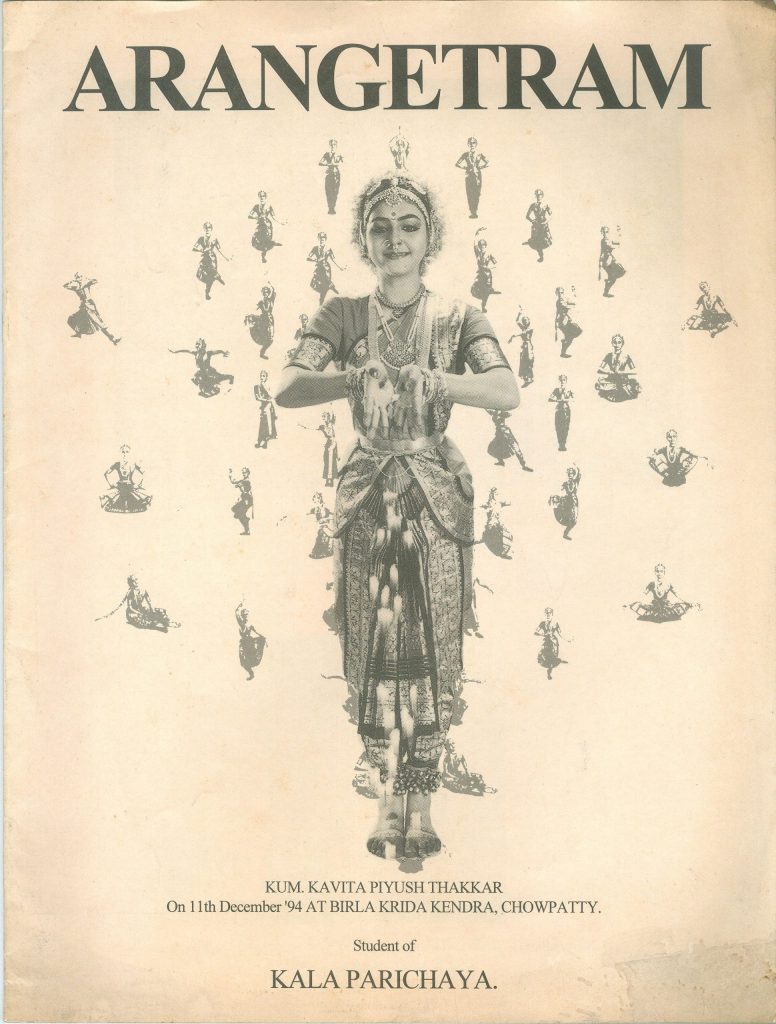

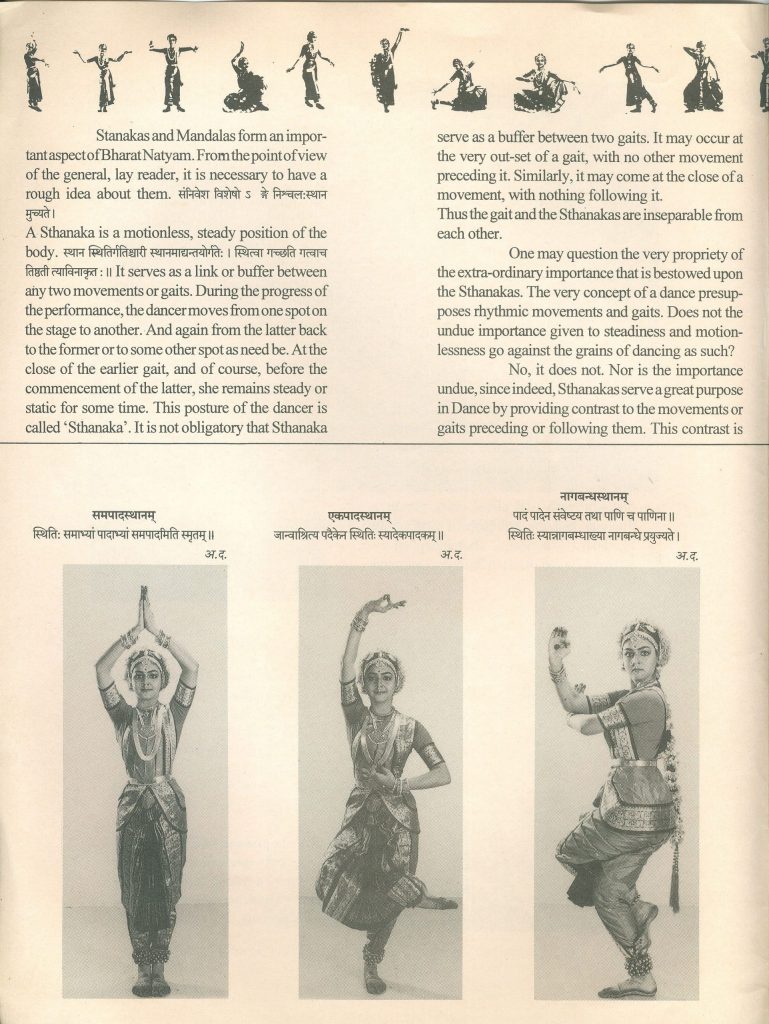

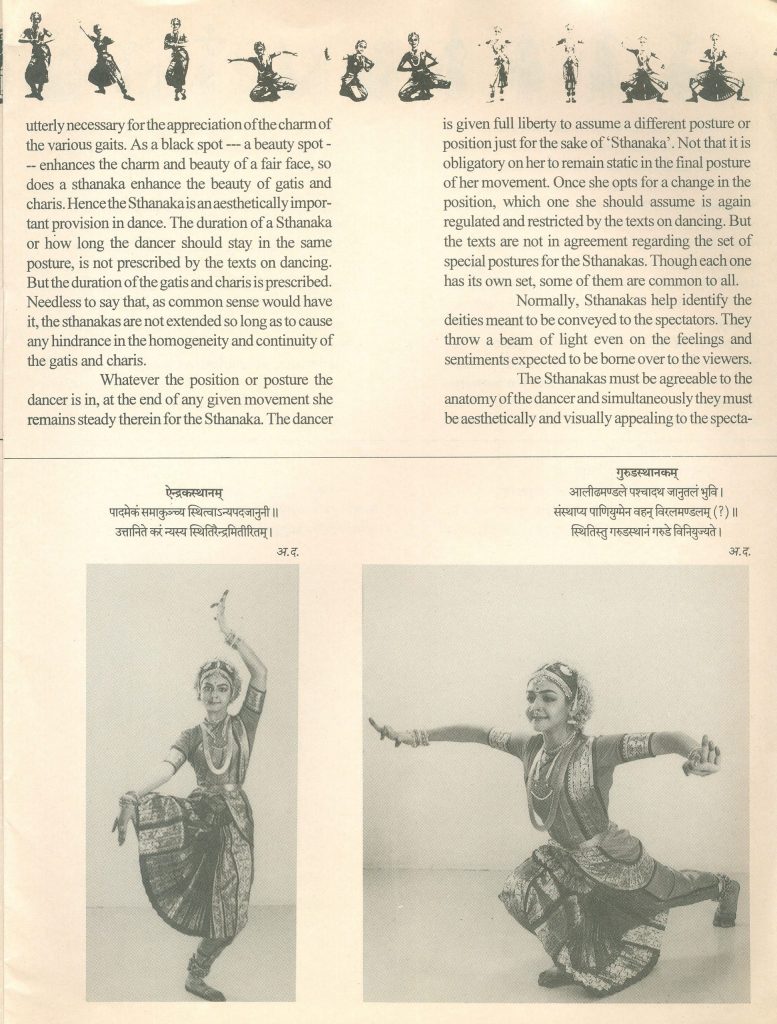

Facilitating Audience Appreciation

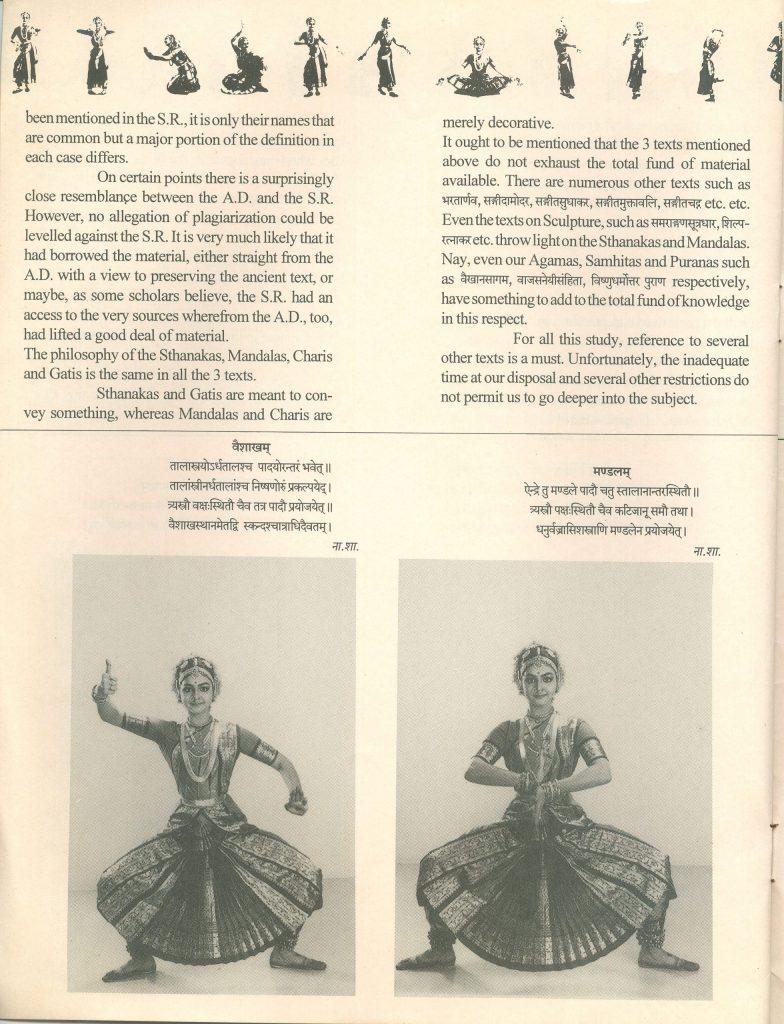

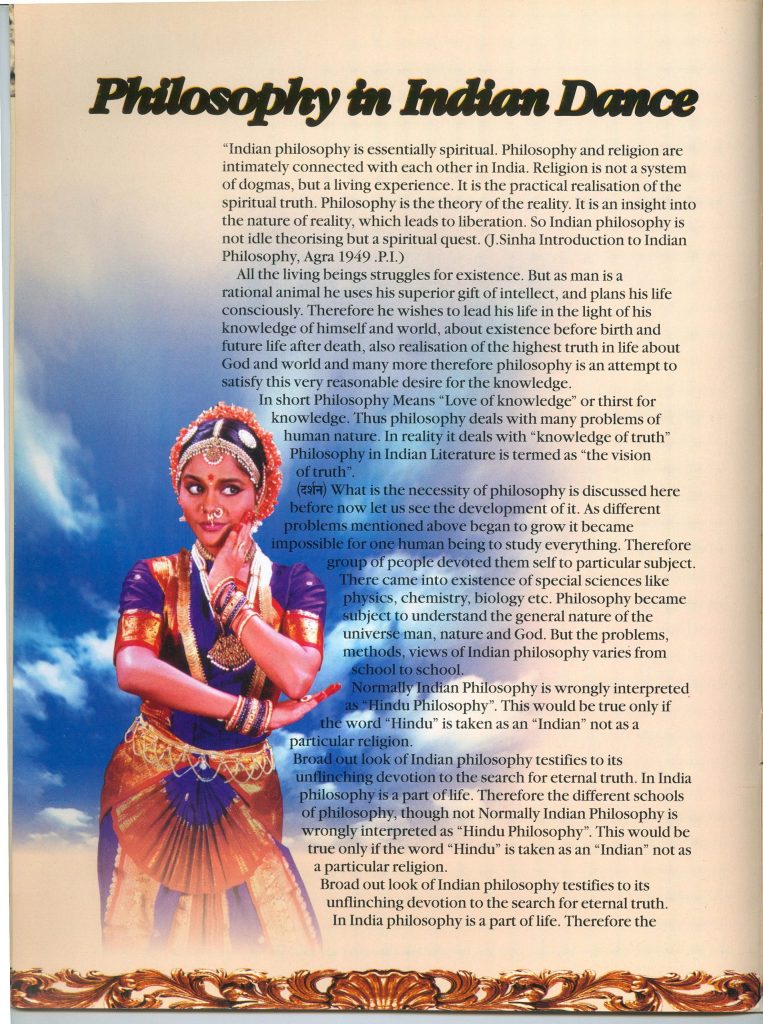

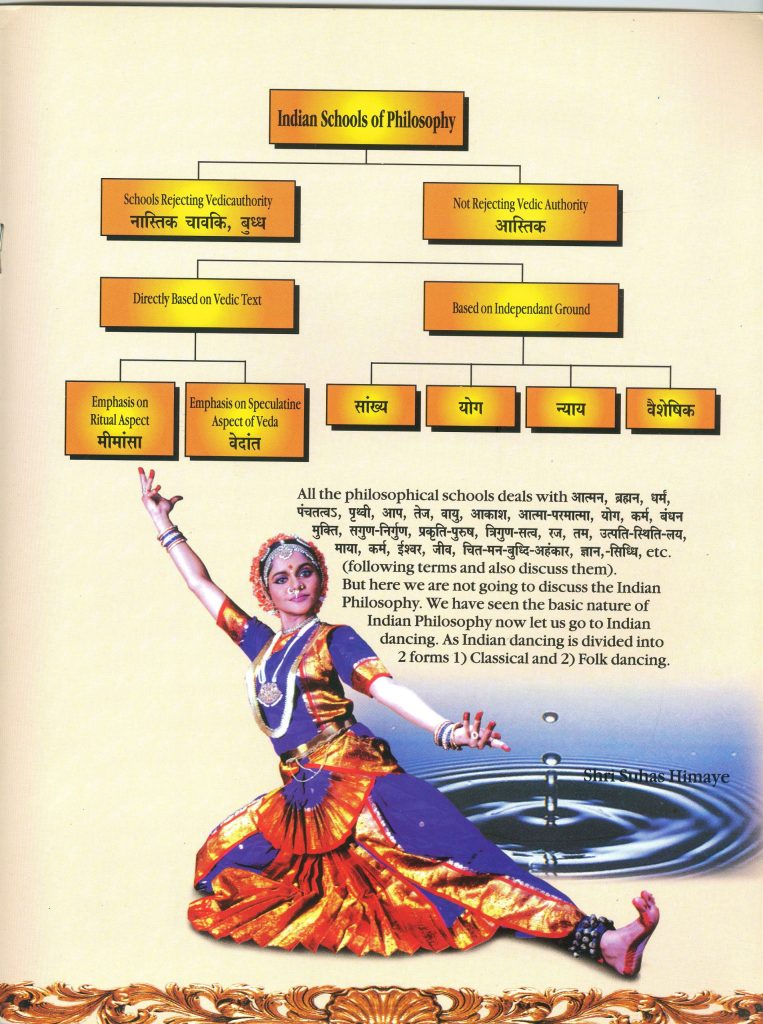

A unique trend in Arangetram invitations from dance institutions in India is an effort to educate the audience about not just Bharatnatyam and its history but also about its philosophy. While most invitations outline about the dance form, its history, and what Arangetram means, there are a few that delve deeper. For instance, Kala Parichaya dance school, run by Sandya Purecha from Mumbai includes illustrations of Sthanakas and Mandalas (motionless poses) in detail in one of their disciple’s Arangetram invitations.

In another invitation, Purecha explains in detail about the Indian philosophy (darshan) and its relationship with dance. Another dance school from New Delhi, Yamini Krishnamurti Institute of Dance dedicated a page to explain the ‘Sampradaya’ in Bharatnatyam and how dance becomes the fifth Veda. Arangetram invitations, therefore, beyond ephemera also become a teaching aid to instruct or initiate the uninitiated, right before the performance.

Parampara (Tradition) vs Renaissance

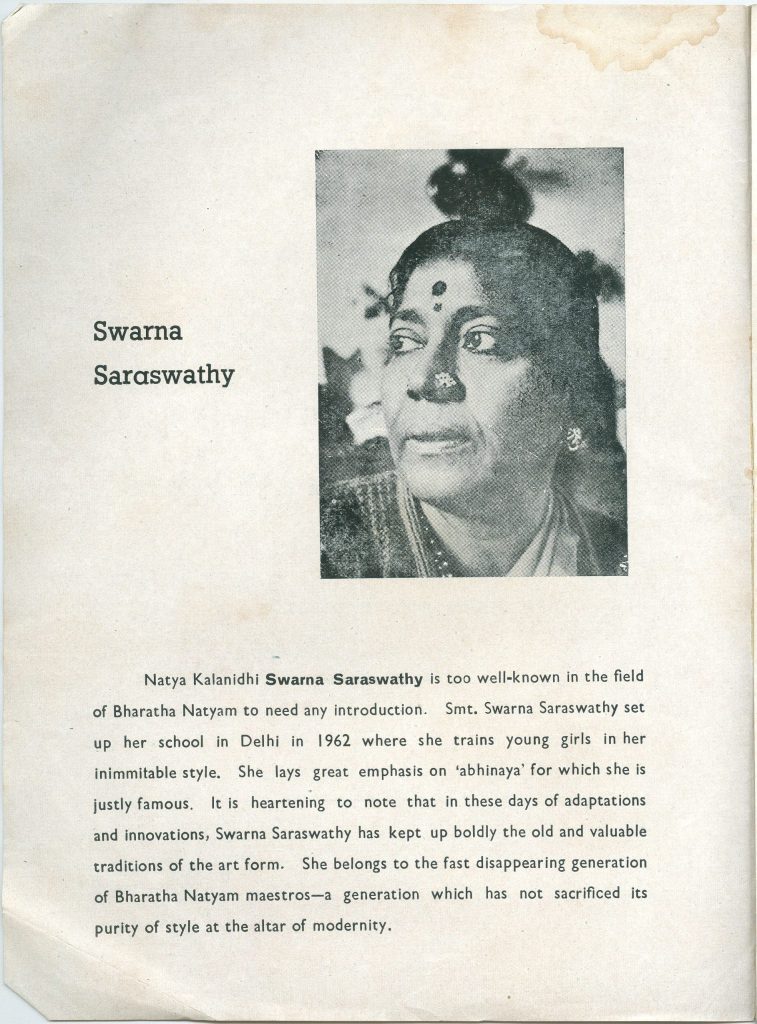

If one zooms out and looks closely at the Arangetram invitations from India, a tension between tradition and renaissance can be sensed. Some invitations emphasize on the need to preserve Bharatnatyam’s centuries-old tradition (parampara) by incorporating phrases like, “purity of style at the altar of modernity”.

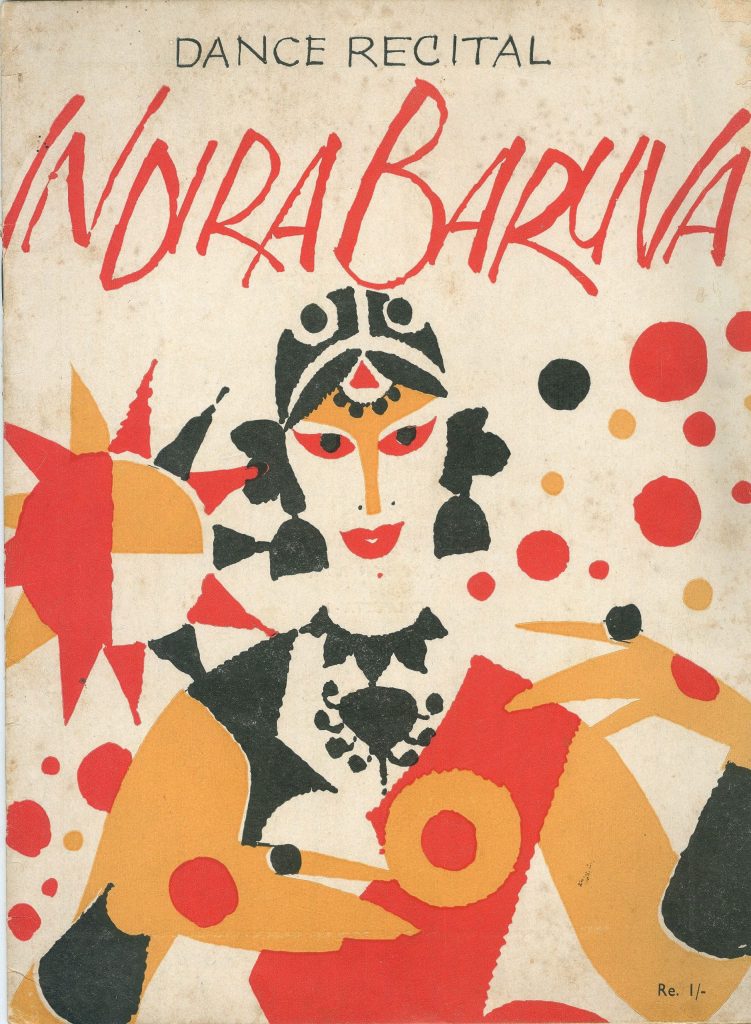

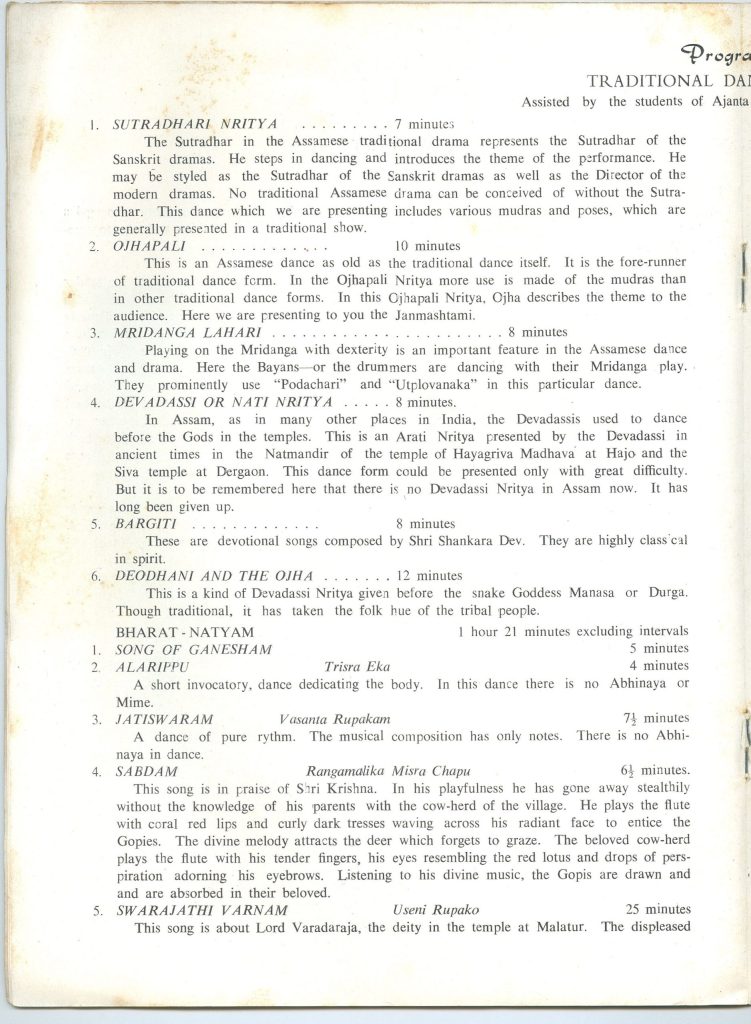

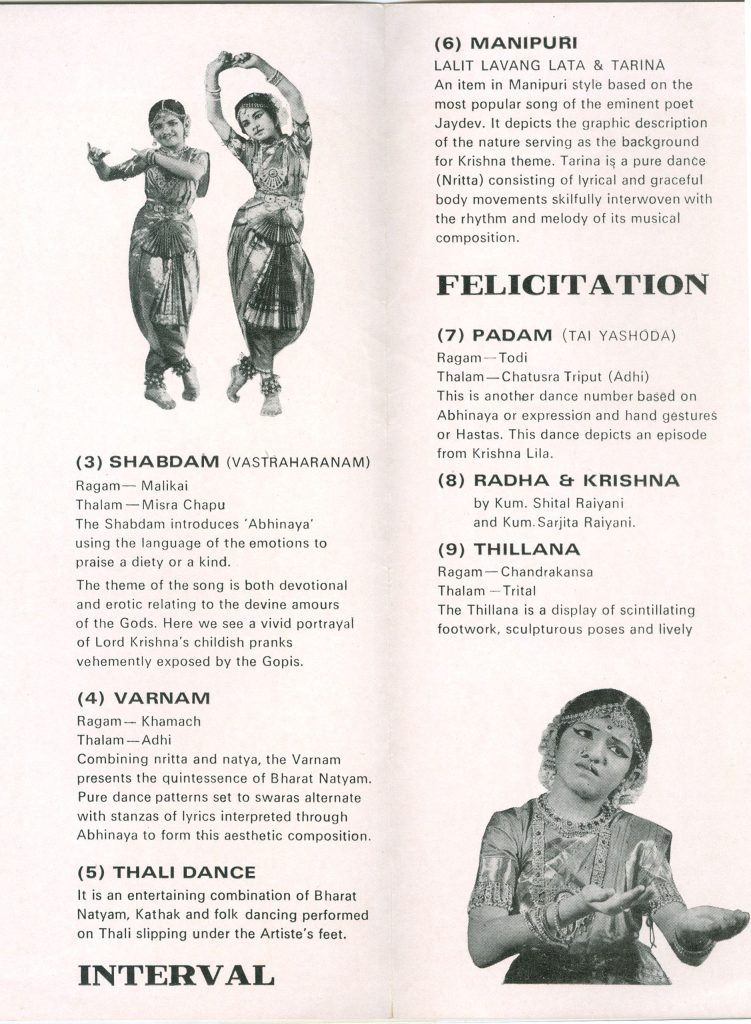

Whereas some invitations focus on bringing out a new-ness in the dance form by explicitly calling it “renaissance” or by mixing other dance forms like Assamese, Thali Dance, Kathak, Odissi, and folk dance like Kurathi Attam with the traditional Bharatnatyam Arangetram repertoire.

Hence, a careful look at the ephemera of Arangetram invitations offers us a glimpse on the varying ideologies present in Bharatnatyam dance form.

A Small Nugget: Arangetram of Dancers of Non-Indian Descent

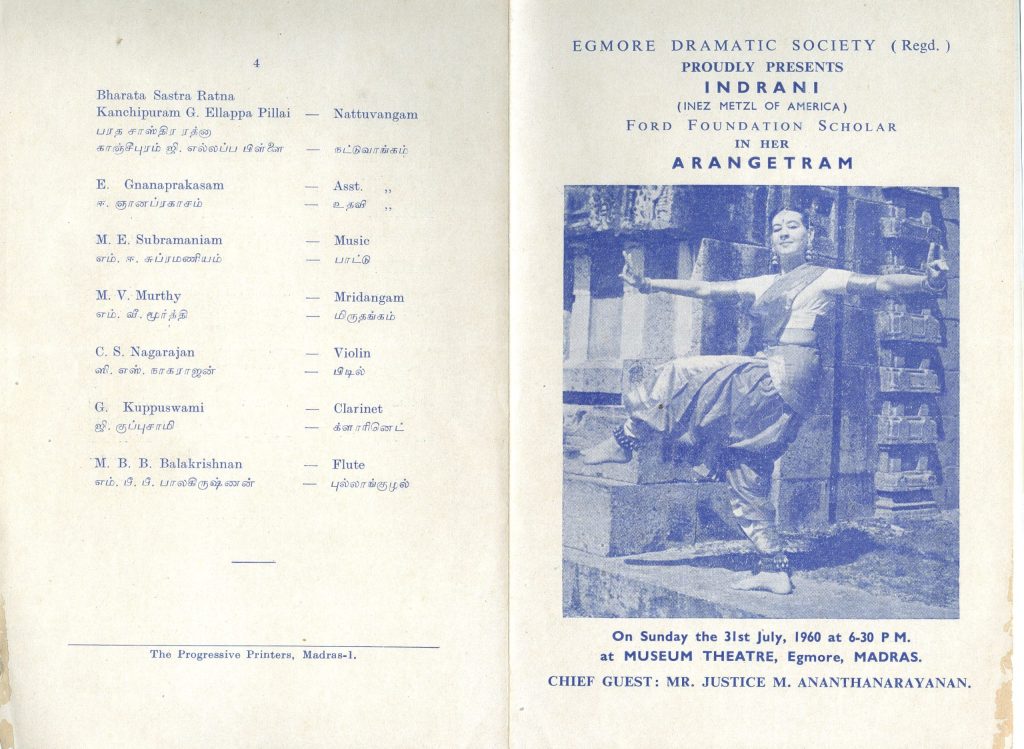

The oldest Arangetram invitation in The Performing Arts Ephemera Collection of Sunil Kothari is from the year 1960. This invitation is of Indrani whose American name, Inez Metzel also finds mention in parenthesis. Indrani, a Ford Foundation scholar in India was presented by the Egmore Dramatic Society based in Madras (now Chennai). The Arangetram program written in both Tamil and English, signify a coming together of two different worlds through dance.

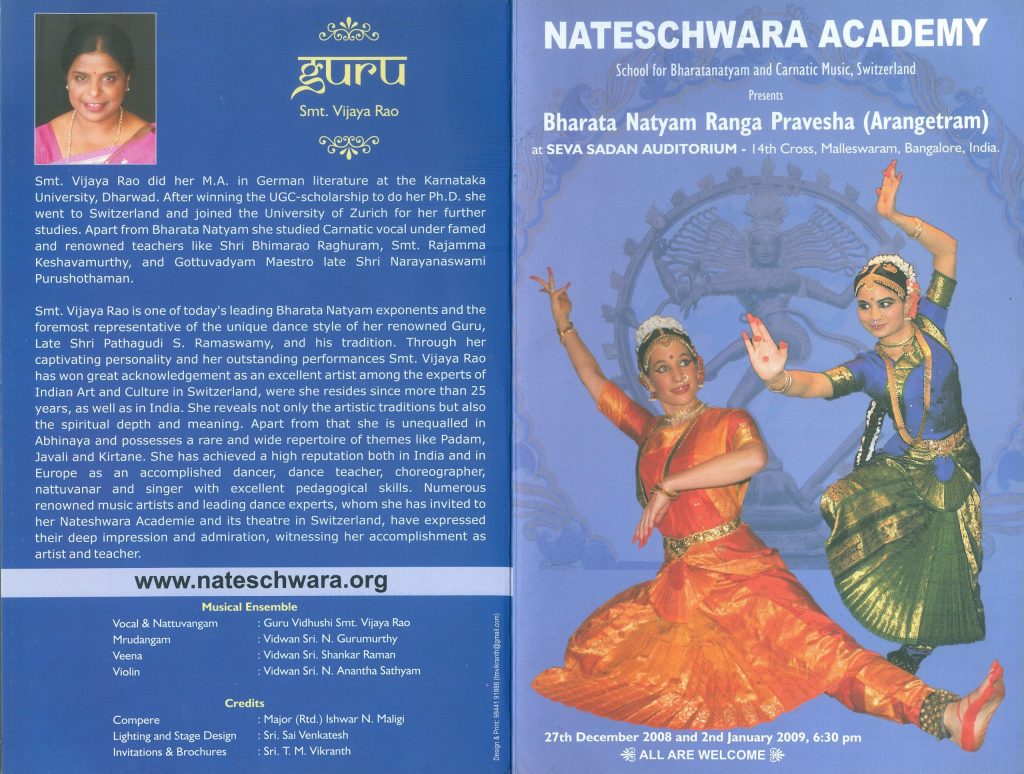

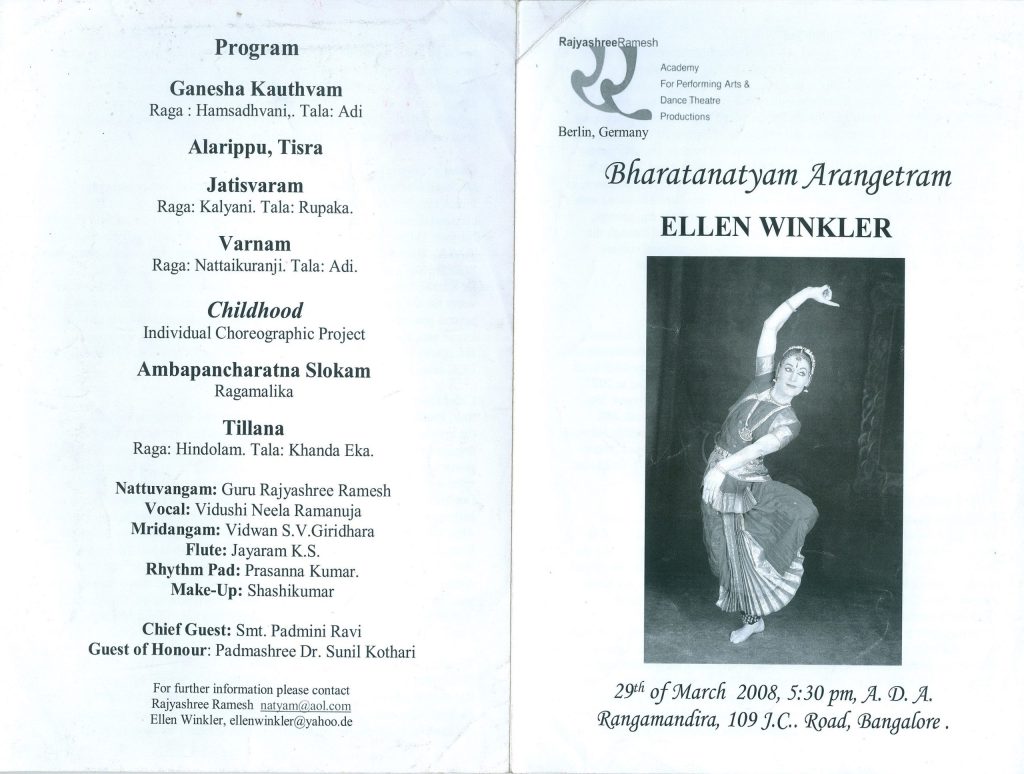

There are seven more invitations of dancers from countries such as Japan, the USA, Sri Lanka, Czech Republic, Nepal, Germany, and Switzerland, who are performing their Arangetram in India. However, the invitations of Rajyashree Ramesh Academy from Germany and Nateschwara Academy from Switzerland are fascinating. Take a look at the documents below:

While the other non-Indian students received their Bharatnatyam training in India by Indian gurus, these two schools are the only ones where the teacher is from the Indian diasporic community. This makes for an interesting case wherein the dance school run abroad chose to do Arangetram of their students (especially non-Indians) in India. Then it is well within reason to speculate that these teachers conducted their pupils’ Arangetrams in India to add legitimacy and credibility to their training which might otherwise lack in a ‘foreign’ land. In addition, the credibility obtained after performing in front of an initiated crowd who understands the dance form is far more than performing in front of a non-initiated audience in a far-off land.

Thank you! A question was raised earlier – “Beyond an invitation to attend, what do these Arangetram invitations tell us?” I hope as you close this tab, you have found an answer to this question along with a better understanding of Arangetram in Bharatnatyam and its role in society. Most importantly, I hope you are able to appreciate the number of stories and research possibilities that ephemera contain. This exhibition is not a culmination of the study of Arangetram through ephemera—rather it is a beginning.

All photos from the Archives and Research Center for Ethnomusicology (ARCE), Gurugram, India.

Works cited:

King, Linda. “‘Lasting but a Day’: Printed Ephemera as Material Culture.” Circa, no. 103 (2003): 33–37. https://doi.org/10.2307/25563911.

Kothari, Sunil. “Guruparampara”. In Bharatnatyam. Mumbai: The Marg Foundation, 2015.

Menon, Sadanand. “A Critical Loss to Dance”. https://englisharchives.mathrubhumi.com/features/specials/a-critic-al-loss-to-indian-dance-1.5313484 (accessed August 15, 2024)

Schofield, Katherine Butler. “Chasing Eurydice: Writing on Music in the Late Mughal World.” Chapter. In Music and Musicians in Late Mughal India: Histories of the Ephemeral, 1748–1858, 1–19. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023.