Timeline of the Grand Trunk Road

Classical India (c.500-c.800 C.E.)

Greco-Buddhist era and the Mauryans (c. 500 B.C.E - 300 C.E.)

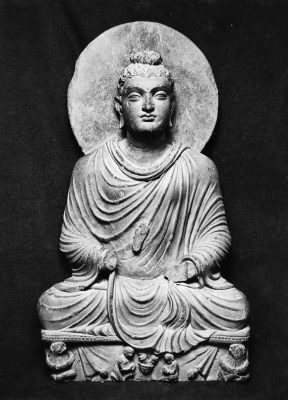

The Greco-Buddhist era saw the makeup of Northern India resoundingly changed. This period saw the rise of Buddhism in the central Gangetic valley and the invasion of Hellenistic populations following Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Ancient known world. The historical importance of the setting of the Uttarapatha would again be demonstrated in Buddhism, as the Buddha himself reached enlightenment in Bodh Gaya and gave his first sermon in Sarnath, both of which sit along the modern GT road. The Uttarapatha also shaped the Greeks’ conquest; their armies would utilize the Khyber pass to cross into the subcontinent and descend eastward along the Ganges before turning around at the battle of Hydapses in 326 B.C.E.

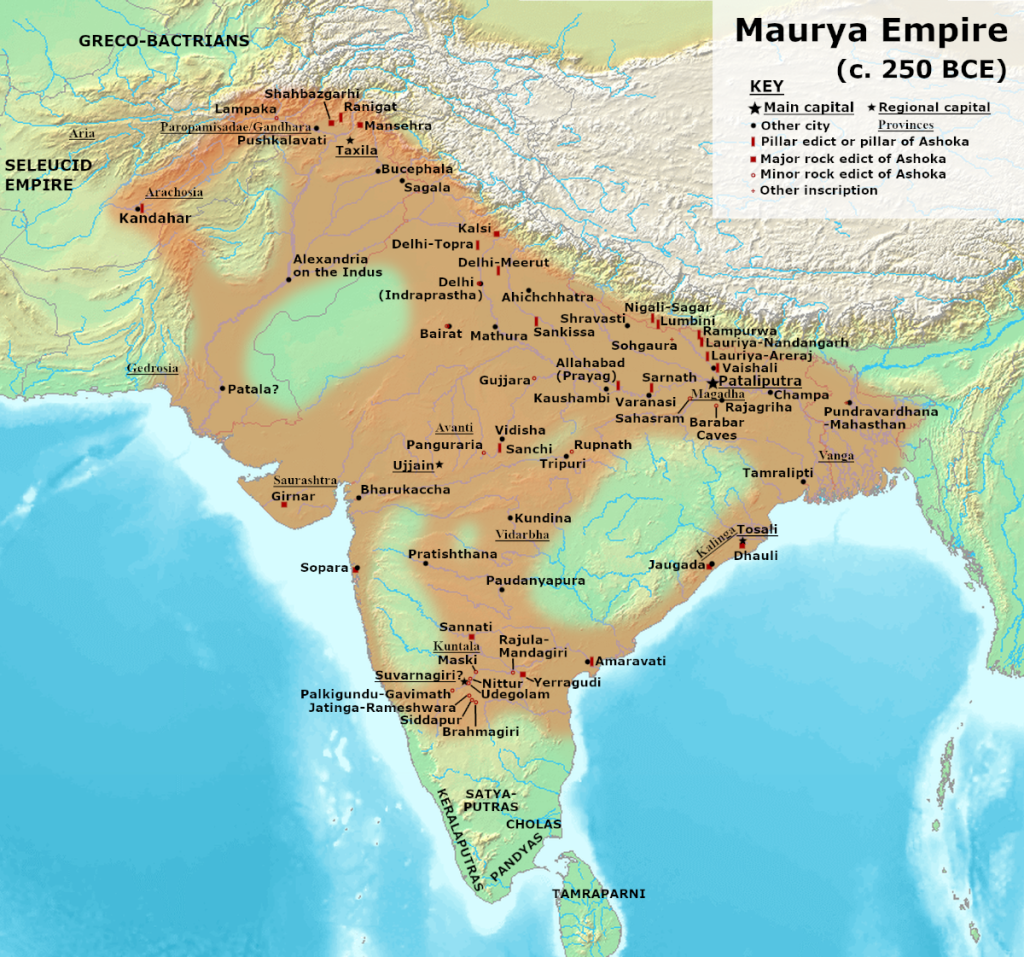

From the east, a rising ruler named Chandragupta Maurya would assert control of Northern India, secure peace with the Greek Seleucid empire to the west, and engage in widespread state-building and infrastructure initiatives across his new kingdom: the Magadha empire. Chandragupta’s realm was massive, extending from Bangladesh in the east to Afghanistan in the west and from the Himalayas in the north to as far south as modern-day Kerala in South India. The Mauryans realized the difficulty in managing such a large kingdom, particularly in the ancient era when communication was a slow and dangerous endeavor. This lead Chandragupta to prioritize building roads to connect the various parts of his empire with its’ Gangetic valley-based capital, Pataliputra, to encourage economic prosperity and optomize political management. Magadha’s Greek ambassador, Megasthenes, provided much of our current knowledge about the management of this new kingdom, notably the official establishment of a trade road in India with stone pillars marking the path every kos(3.22 kilometers/1.1 miles) running from Pataliputra to Taxila in modern-day Afghanistan. This new route, along the modern GT road, was established in the 3rd c. B.C.E. based on the Achaemenid’s Great Khursan road, leading to the construction of guest houses in major cities. The third Mauryan ruler, Ashoka the Great, further upgraded the royal highway network by providing several features that would define the route into the modern day by planting trees along the path to provide shade and direction to travelers, digging wells every half kos to provide water, and constructing nimisdhayas, a predecessor to the caravansarai, along the kingdom’s routes.

“On the roads banyan-trees were caused to be planted by me, (in order that) they might afford shade to cattle and men, (and) mango-groves were caused to be planted. And (at intervals) of eight kos wells were caused to be dug by me, and flights of steps (for descending into the water) were caused to be built. Numerous drinking-places were caused to be established by me, here and there, for the enjoyment of cattle and men. [But] this so-called enjoyment (is) [of little consequence]. For with various comforts have the people been blessed both by former kings and by myself. But by me this has been done for the following purpose: that they might conform to that practice of morality.”

-Ashoka, Major Pillar Edict No.7

Gupta Period (c. 300. - 800 C.E.)

The Mauryan’s rule over the subcontinent would falter in 185 B.C.E., leading northern India into a tumultuous period marked by the rise and conflict of Indo-Greek kingdoms in modern-day Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Northwest India and relatively short-lived dynasties like the Shunga and Kushans. Still, the beneficial impact of the Mauryan road system on India would extend well past the decline of their empire, attested in the foreign records of cultures across the ancient old world from Han-dynasty China to the Roman Empire. This tumultuous period ceased with the rise of the Gupta empire(c. 240 C.E.- c.550 C.E.), ruled by another leader named Chandragupta from the east. The Guptas continued to utilize the Uttarapatha to engage in global trade, exchanging goods like high quality, rust-resistant Indian iron and jewelry for Chinese silk or African ivory, and continued the construction of guest houses for traders along the route.

Little knowledge remains of what these sarais and the road looked like during this period, leaving contemporary texts and the previously mentioned foreign accounts, like those of the 5th c. C.E. Chinese explorer Faixan as the greatest indicator of what it was like to travel along this route. Faixan’s accounts outline his travel along the Uttarapatha from the northwest of the subcontinent, detailing the kingdom’s abundant wealth, free public health centers and guest houses in cities, and the interactions between the growing Buddhist population with the other religions on the subcontinent. On his return to China, Faixan would translate the Buddhist texts he had procured in India from Sanskrit to Chinese in a cultural exchange that would change the course of East Asia’s religious and social makeup forever, all due to the Uttarapatha’s prosperous and facilitative path.

Bibliography

Aali, F. “Achaemanid’s Influence on Maurya Dynasty.” International Journal of Research 3, no. 10 (2016): 1069-1083. https://journals.pen2print.org/index.php/ijr/article/view/4701/4518.

Akter, I. (2020). Economic systems of Ancient India: Maurya and Gupta empire. American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research, 4(9), 218-229.

Dar, Saifur Rahman. “Caravanserais along the Grand Trunk Road in Pakistan.” In The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce, edited by Vadime Elisseeff. Paris: UNESCO Publishing/Berghahn Books, 2000.

Faxian. 1886. A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms Being an Account by the Chinese Monk Fâ-Hien of His Travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399-414) in Search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline.

Fleming, David. “Where Was Achaemenid India?” Bulletin of the Asia Institute 7 (1993): 67–72. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24048427.

Parpola, Asko. “Deciphering the Indus Script.” Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Parpola, Asko. “‘Royal’ Chariot Burials of Sanauli near Delhi and Archaeological Correlates of Prehistoric Indo-Iranian Languages.” Studia Orientalia Electronica 8, no. 1 (2020).

Witzel, Michael. “Early Sanskritization: Origin and Development of the Kuru State.” Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 1, no. 4 (1995).