Mughal Architecture along the GT Road

“Now the true account of the road in question is the following: Royal stations exist along its whole length, and excellent caravansarais; and throughout, it traverses an inhabited tract, and is free from danger.”

– Herodotus on India, Histories (5.52)

Caravansarais

A fixture of any of the world’s great transportation routes is the presence of shelters for traders and travelers to seek respite from their journeys. While today, our airports and longer highways are surrounded by the ubiquitous three-star, continental breakfast buffet-serving, name-brand hotel, the great empires of ages past sought to provide safe refuge for travelers and demonstrate their domain’s power and beauty. Travel and trade as a comfortable endeavor is a relatively new development in the human story, and the desire to leave one’s home to explore the outside world would have inevitably been deterred by the thought of a months-long journey exposed to thieves and the elements. Enter the caravansarai, from the original Persian kārvān-sarāy or “traders palace.” These multi-purposed roadside inns sheltered travelers, enabled cultural exchange, religious practice, and, most importantly, provided security along the remote stretches of long-reaching empires. The remains of caravansarais span across the Silk Road and the Islamic world from Fez, Morocco’s Foundouk el-Nejjarine, to Bara Katra in Dhaka, Bangladesh, capturing the hearts of archaeologists, historians, and the dusty, explorative, camel-riding dreamscapes of adventure-hungry youth.

Caravansarais across the world

The Indian Caravansarai’s origins have been lost to time, but some of the first recorded instances of guest house construction began in the Mauryan period. Charitable guest houses in cities called Dharma Vasathas were constructed by Chandragupta Maurya for Brahmins and traveling religious minorities. The construction of sarais would continue under his grandson, Ashoka the Great, who first designated the predecessor of GT road’s route in the 3rd century B.C.E. and built guest houses called nimisdhayas every eight kos(~15 km/9 miles) after being inspired by the Achaemenid Persians’ Khorasan road. Unfortunately, we only know of these sites through literary and historical sources, as the only surviving sarais along the modern GT road were built after the expansion of the Mughal Empire into the subcontinent, hinting at the use of less resistant building materials like mud-brick in early sarai construction.

The late Medieval era would see a revitalization of what would become the GT road under direction of the Mughal Dynasty and Sher Shah Suri, an Afghan-Bihari ruler who briefly dethroned the dynasty and made the route a critical lifeline and ambassador of his power with 1,700 sarais as its’ focal points. Near and far, visitors from west and east alike remarked on the great works’ safety, beauty, and multicultural makeup, best encapsulated by 17th-century French physician François Bernier’s remarks that: “If there were twenty-such like accommodations in different parts of Paris, foreigners newly arriving would not be so ill-put as they frequently are.”

Caravansarai Architecture

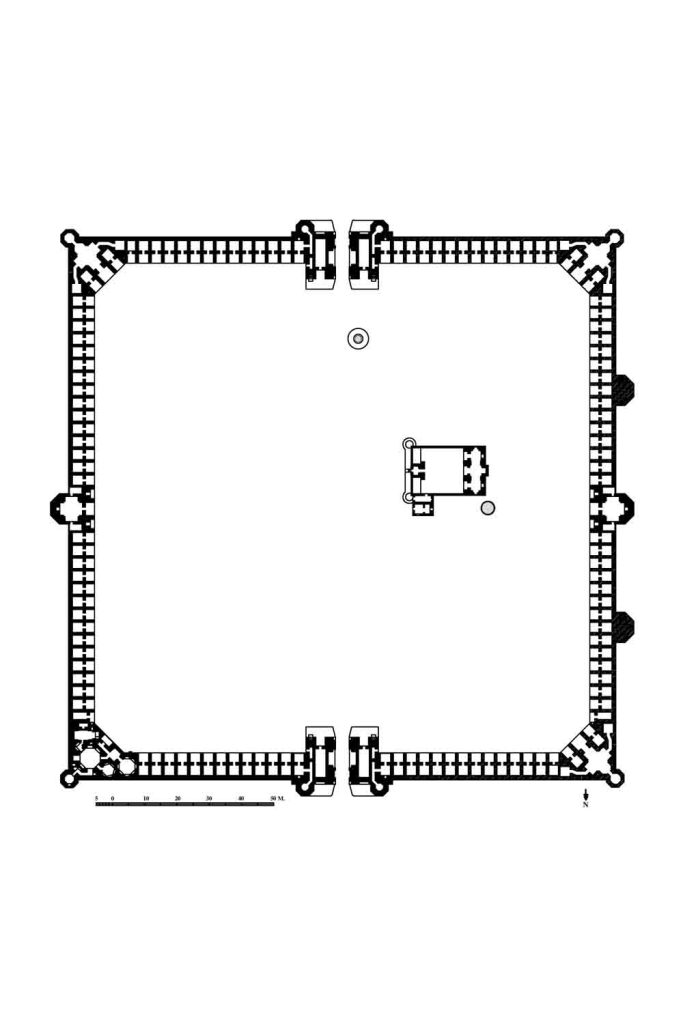

Visitors to GT road-adjacent Mughal Caravansarais will generally find themselves in a brick structure built according to the Sassanid Persian-descended Iwan architectural plan. Easily recognized for its use in countless Islamic tombs and mosques, this style contains an expansive interior courtyard, which usually features a well, small mosque, and bathhouse bounded by protective walls with interior apartments.

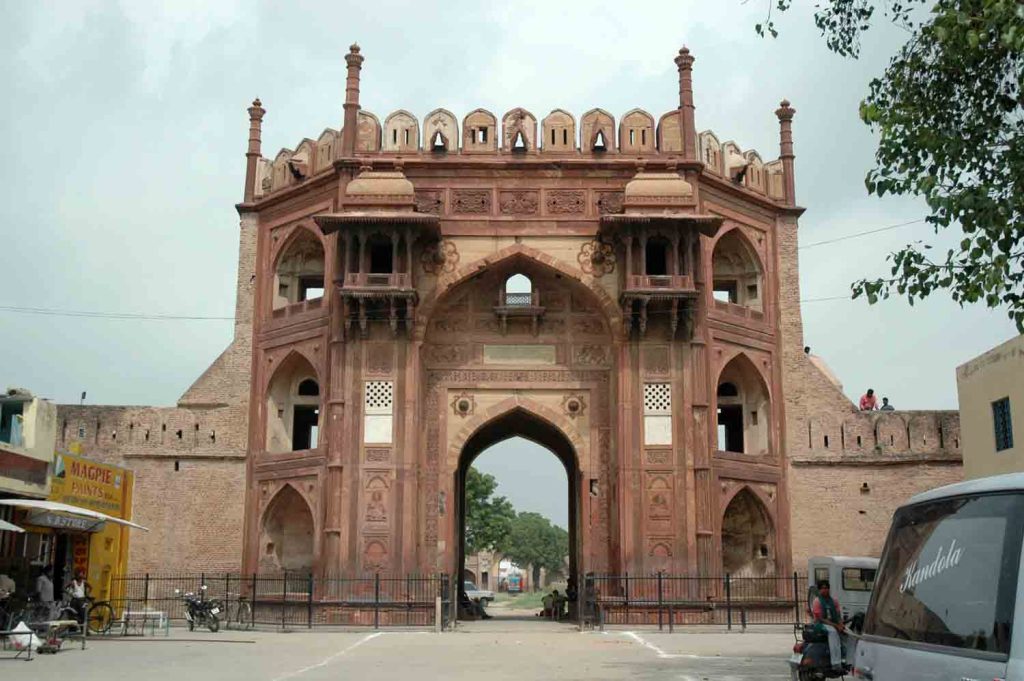

The defining aspect of this architectural plan is the presence of massive, bastioned arched gates called Iwans, which open up the enclosed complex. Most Mughal sarais from after Akbar’s time feature two gates generally named after the significant city they are leading to (for example, Sarai Doraha’s gates in Punjab are called Delhi gate and Lahore gate) which mark the exit and entrance of the Sarai. These gates are ornamented with Indo-Islamic geometrical and floral patterns and decorative enclaves called Pishtaqs. Within the Iwans lie concealed bastions and apartments for the sarai’s administrators and soldiers, with the corners of the structure harboring larger apartments that acted as a “suite” for particularly important guests. Mughal Sarai gates are built primarily in two styles: the first comprising of a higher central facade with angled sides seen in sarais like Nurmahal, and the second, seen in sites like Sarai Amant Khan, favoring a broad, single-planed facade flanked by octagonal towers crowned with a dome or a bastion-like structure called a chhatri.

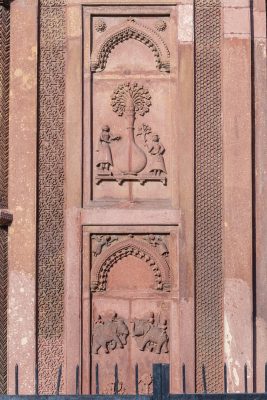

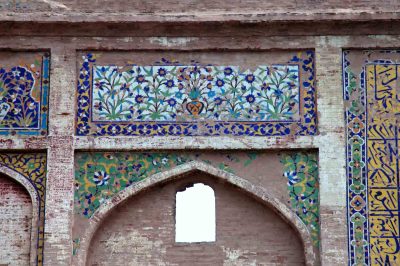

Within these structures’s walls lies the last vestiges of Mughal ornamentation, with the faded hues of distinctly Indian floral and natural designs intermingling with typical Islamic inscriptions and geometry. A variety of these motifs are found muraled on the inside of gateways like in Sarai Baradpur, in the form of carved animate motifs seen at sites like Sarai Nurmahal, or in the Iranic glazed tiles of Sarai Amant Khan.

Mughal Sarais were more than just simple way stations; their ornate status created communities in and of themselves that developed the immediate area around them, and in the case of Sarai Amant Khan and Sarai Nurmahal, even provided the name for the towns that they now occupy. Sarais were even built with technological features to provide the utmost luxury for its passing inhabitants: Aam Khas Bagh, a royal sarai built by Shah Jahan to ease his travels between Lahore and Delhi in modern-day Sirhind, Punjab, features sophisticated plumbing, hot water for the Sarai’s baths, and even an early predecessor of air conditioning.

Bibliography

Archaeological Survey of India. The Tomb of Mariam Zamani. Informational Plaque for Tomb of Mariam Zamani. Sikandra, Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India. Viewed August 3, 2024.

Dar, S. R. 2000. “Caravansarais Along the Grand Trunk Road in Pakistan.” In The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce, 158-178. Paris: UNESCO Publishing/Berghann Books.

Parihar, Subhash. 2009. “Travelling with the Mughals: A Survey of the Agra-Lahore Highway.” Marg 60 (4).

Singh, Raghubir. 1995. The Grand Trunk Road: A Passage Through India. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB1012507X.

Sinha, Vandana. 2019. “Documentation of Indo-Islamic Architecture Built Along a 16th-century Highway.” Art Libraries Journal 44 (3): 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1017/alj.2019.14.