The Grand Trunk Road Today

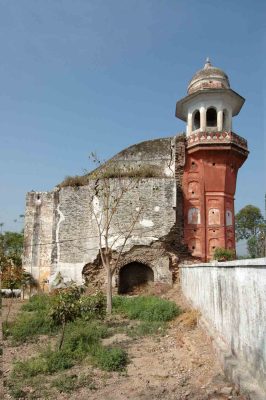

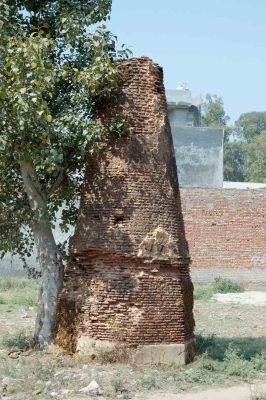

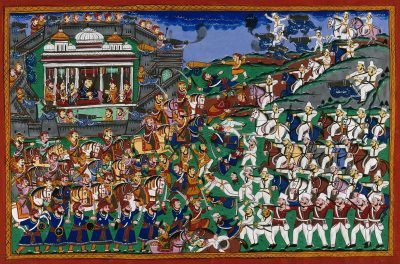

The era of Akbar, Barbur, and Aurangzeb faded into the past, and the once-great Mughal empire found itself deteriorating rapidly. By 1771, only 64 years after the death of Aurangzeb, the Mughals would begin ceding the majority of their remaining territory to the British East India Company and finally be deposed in 1858 after an unsuccessful rebellion against the colonial power. As the grandeur of the dynasty tarnished, so too would its constructions: caravansarais fell into ruin, their apartments no longer perfumed with the wares of incense-laden traders but rather the musky smells of bats and rot. Once vibrant floral murals would chip and fade, with only a fine layer of plaster harkening back to a cultural renaissance under a long-gone empire. Kos Minars, once sentinels along the subcontinent’s overland trade routes, found themselves engulfed by wilderness and farmland as the memory of foreign traders and great journeys became relegated to the unspeaking stone and brick of the mile markers. Still, the road survived.

The British realized the Uttarapatha’s strength, and just as the Mauryans and the Mughals did before, capitalized on the route to enforce the security and economy of their new colony. The Mughal’s Badshahi Sadak was rechristened as the Grand Trunk Road in 1839 following the route’s straightening and paving by the British East India Company. The new Kabul-Kolkata route was a lifeline to the British Raj, its highways both facilitating the transport of troops to secure control across the subcontinent and enrichening its’ colonial overlord’s coffers through bustling trade. The Mughal ruins alongside the new GT road would similarly re-emerge, exemplified by the destruction of Haryana’s Sarai Gharunda by the British during the revolt of 1857 to dislodge mutineers who found refuge in the walls of the rest house.

Caravansarais truly took on a new life in India during the 1947 partition, where they would again provide shelter and a community for weary travelers not seeking fortune through trade, but from a horrifically perilous human rights catastrophe. These sarais became communities in and of themselves for the fleeing Muslim and Hindu refugees who had used the GT road to escape the partiton. These refugees worked to restore and rebuild the apartments, open shops, build temples, and even expand to create safe havens just as Sher Shah, Akbar, Ashoka, or Jahangir did. Some excellent examples of these modern-day sarai communities include Sarai Amant Khan in Punjab, Akbari Sarai in Uttar Pradesh, and Mughal Sarai in Taraori, Haryana.

Dr. Vandana Sinha from AIIS’s Center of Art and Archaeology interviewing Nandalal, one of the first inhabitants of the Mughal Sarai at Taraori and the child of partition refugees:

Audio Transcript:

Vandana: Ok so I am interviewing Nandalal ji, his interview ID is AFCP_ OH_001. Your age is 70 years. You are male, your caste is Saluja, you are Multani or Punjabi and your business is that you are a retired businessman, and you live in the fort of Taravdi.

Nandalal: Yes.

Vandana: Yes. So here I will write Haryana. Now where is your family from, like where are your parents from?

Nandalal: They were from Pakistan.

Vandana: Okay, where were they from in Pakistan?

Nandalal: From Gaven.

Vandana: Which place?

Nandalal: Gaven Gaven.

Vandana: Gaven?

Nandalal: Yes. Multan, Gaven. We are from Multan.

Vandana: Yes, is Gaven the name of a place or a village?

Nandalal: It was the name of a village.

Vandana: Gaven. G-A-V-E-N is in Multan. Was that a district of Multan?

Nandalal: Multan was the district, right.

Vandana: There was Multan district?

Nandalal: Yes, there was a district.

Vandana: Ok ok, right. Multan district, in which Multan is the name of a village in Pakistan. Okay, Multan district.

How long have you been living in this area? When did you arrive here?

Nandalal: When we got independence in 1947, our elders came in 1947. We are born here.

Vandana: You were born here?

Nandalal: Yes, here, in 1954.

Vandana: Okay, you were born in 1954?

Nandalal: Yes, in India.

Vandana: Ok, where in India?

Nandalal: Right here.

Vandana: In Taravdi?

Nandalal: In Taravdi itself.

Vandana: Ok, ok. Your father came here in 1947?

Nandalal: Yes.

Vandana: Yes, the same thing has come up here that your father came from Multan, so it will be written that you have come and settled from somewhere else. We will write here that you have come to settle here from Gaven, Multan. So your parents, I mean they obviously came here because of the partition, right?

Nandalal: Yes, they came after the violence broke out there.

Vandana: Yes, yes.

Nandalal: The Hindus who came from Pakistan.

Today, whether in India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, or Bangladesh, the GT road remains a testament to the resilience of humanity and our connections. While any historical site across the world can be visited and appreciated, the Grand Trunk Road is one that lives and breathes just as its’ course-setting Ganges does. In the face of modern progress, thousands of years watch down as new stories and constructions shape the route just as it had been shaped in the glory days of the Mughals: few journeys and few experiences can be lived that are so ancient and yet so new. Centuries from now, the Uttarapatha will undoubtedly remain in one form or another as its rich causeways fuel the beating hearts of future empires and feed the same populations it has funneled into its continent-spanning embrace; all that is left is to experience the route yourself and find your part in the Grand Trunk Road’s story.

Bibliography

- Sinha, Vandana. “Documentation of Indo-Islamic Architecture Built Along a 16th-century Highway.” Art Libraries Journal 44, no. 3 (2019): 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1017/alj.2019.14.