Mughal Architecture along the GT Road

Gardens

Crossing from the crowded maze and sensory overload of India’s streets to the tranquility and gently running streams of gardens, it is clear to see why the Mughals put such a focus on the construction of peaceful spaces within their empire. This interest originates well before the Mughals’ time in India: the construction of gardens and green spaces was a rather sophisticated element of Timurid culture, serving as a multi-purpose place dedicated to beauty that acted as a court or dining hall and a source of agricultural bounty to service their royal courts. Barbur, the first member of the Mughal dynasty, found India’s lack of gardens in 1526 so unappealing that he ordered the construction of gardens throughout his new territory. Today, travelers along the Grand Trunk Road can still traverse India’s oldest surviving Mughal garden at Agra’s Aam Bagh and find relief from the city’s hectic streets in a geometrically formatted, beautifully terraced garden containing a royal bath house.

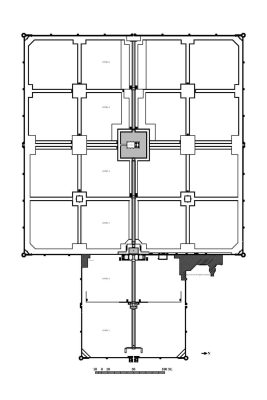

These gardens were historically believed to be built in the Persian Charbagh style, which entails a quadrilaterally-dissected garden style built around the description of heaven found in the Quran as a garden split by four rivers. The origin of the Charbagh style has shifted to central Asia, as the term itself most likely originated under Timurid rulers to describe their multi-use, religiously inspired green spaces.

While this style of garden can be found across most of the Islamic world, the most famous example of the Charbagh style is the world-renowned symbol of India: the Taj Mahal in Agra. Both the Taj Mahal and its predecessor, Humayun’s tomb, are built with square plots intersected with water features to evoke the Muslim conception of paradise, with the main tomb complex situated at the center or near the back of the gardens as the Taj Mahal is. The botanical makeup of these gardens has considerably shifted over time due to foreign influence, with the original medicinal trees and dense gardens containing melon, grapes, and roses felled and replaced by the British to fit a more English-style garden with open lawns and viewpoints for the massive mausoleum.

Outside of these well-preserved UNESCO sites in cities, gardens in more rural areas of the GT road, like those found at Barbur’s own Kabuli Bagh complex in Panipat, Haryana (itself modeled after the gardens of the Timurid capital, Samarqand) serve only as a scarcely concealed reminder for the dynasty’s once great power. A particularly auspicious example is the garden of Kalanuar, once the site of Akbar’s coronation. Today, this garden has fallen into ruin; the rubble of its intricate irrigation network now only happened upon by farmers at work in a modern-day field that the royal garden once occupied. An exception to this ruin is the Mughal Garden in Pinjore, Haryana, which today remains as one of the few intact Mughal terraced gardens and has become a popular picnic spot for travelers heading to the Himalayas from the plains of North India.

Bibliography

Cornell, Vincent J. 2007. Voices of Islam: Voices of Art, Beauty, and Science. Praeger. Asher, Catherine Blanshard. Architecture of Mughal India. The New Cambridge History of India, Part I, Vol. 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 9780521267281.

Parodi, Laura E. 2017. “The Taj Mahal and the Garden Tradition of the Mughals.” Orientations 48 (3): 118-25.Koch, E. Mughal Architecture: An Outline of its History and Development (1526-1858). Munich: Prestel, 1991.

Sinha, Vandana. 2019. “Documentation of Indo-Islamic Architecture Built Along a 16th-century Highway.” Art Libraries Journal 44 (3): 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1017/alj.2019.14. Petersen, Andrew. Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. London: Routledge, 1996.