Timeline of the Grand Trunk Road

Early Medieval India (c.800-1526 C.E.)

The Delhi Sultanate and Medieval India (c. 800-1526 C.E.)

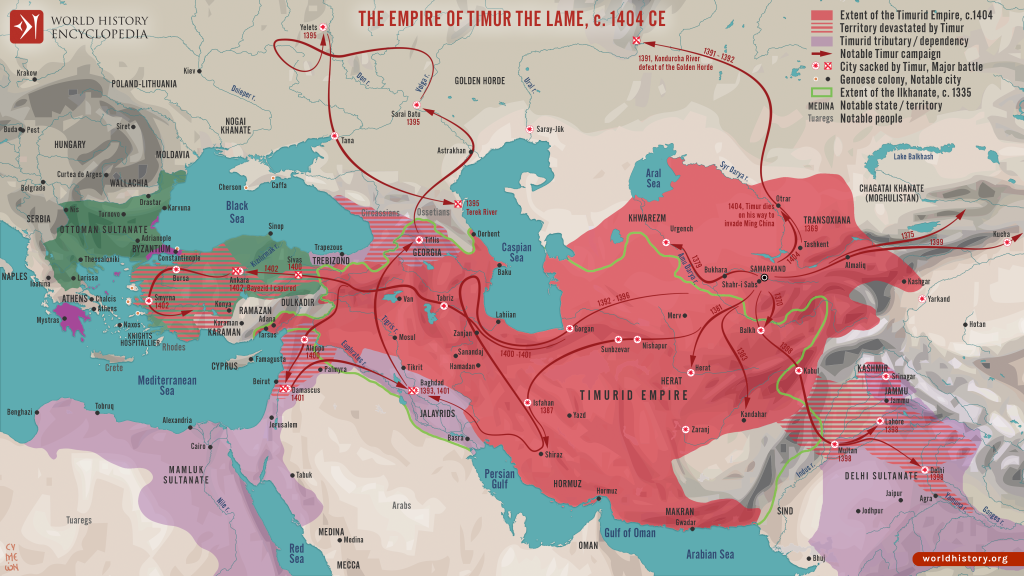

The Gupta empire collapsed, again plunging North India into a period of conflict in the Middle Ages as the tripartite struggle between the Prathiharas, Palas, and Rashtrakutas fought over control of the Gangetic Valley. Repeated invasions from the east by the Mongol horde from 1221-1327 C.E. would occupy Delhi’s sultans as nearby Middle Eastern and Central Asian empires fell into chaos as the Mongols sacked the centers of the Islamic golden age in Cairo, Baghdad, and Merv. This instability would reach its pinnacle with the 1398 arrival of Tamerlane(Timur the Great), a descendent of Genghis Khan and ancestor of the Mughals. Tamerlane was spurred by a self-proclaimed desire to “to war with the infidels, the enemies of the Mohammadan religion; and by this religious warfare to acquire some claim to reward in the life to come” so that “the army of Islam might gain something by plundering the wealth and valuables of the infidels.”

Traveling from Samarqand in modern-day Uzbekistan to the Khyber pass and along the Gangetic valley, Tamerlane’s armies pillaged as they advanced to Delhi, ransacking the trade-generated riches of the city and killing or capturing hundreds of thousands in one of the most brutal scorched earth conquests ever witnessed by humanity. The period between these two sacks saw the route itself change. The sack of Lahore in 1241 led to the Uttarapatha’s path reset further south into Multan, only being restored after the devastation caused by Tamerlane. Still, despite the relative chaos and instability of the subcontinent, urban life and trade would continue to flourish throughout this period.

The next major accounts of a state-led revitalization of the road occur during this Delhi Sultanate period(1206-1526 C.E.). Turkish Muslim rulers from Central Asia established sultanates across the Gangetic valley after crossing into the subcontinent on the Uttarapatha and began to prioritize the road once again. The reign of Mohommad bin Tulaq (1324-1351 C.E.) would again see Caravansarais constructed along the Sultanate’s royal road from Delhi to Daultabad, his new capital in modern-day Maharashtra. Under the leadership of his son, Firoze Shah Tulaq (1351-1387 C.E.), Delhi was revitalized with more than 120 hospitals and sarais which provided free shelter and food for travelers for up to three days. Under the 1488-1511 A.D. reign of Sikander Lodi, holy bathing sites for Hindus were provided with sarais, mosques, schools, and Bazaars.

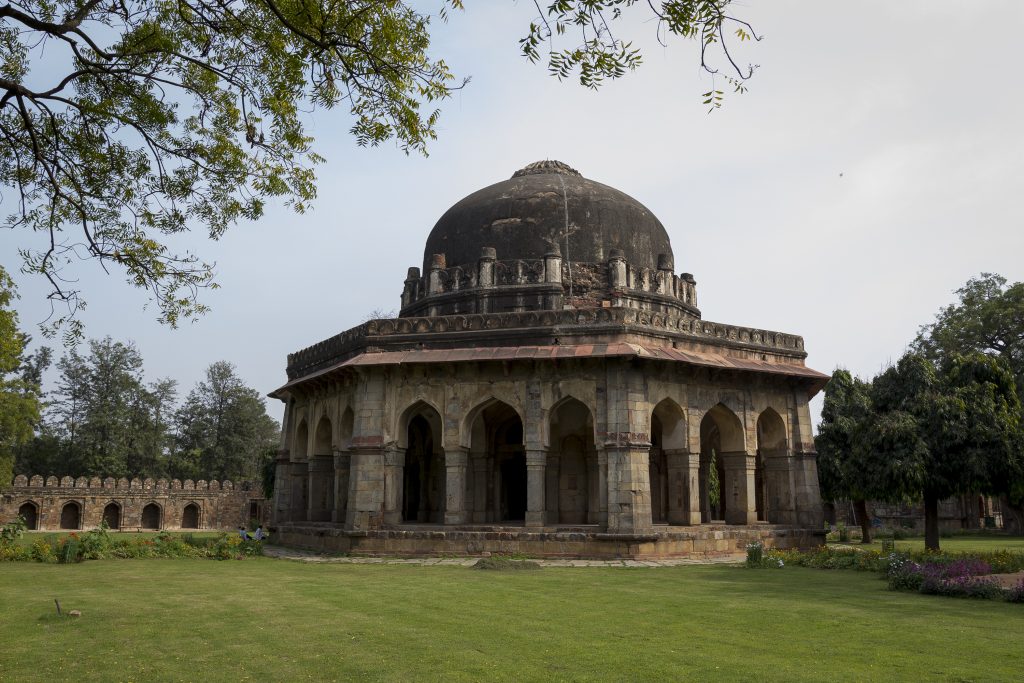

The Delhi sultanate period also witnessed the first interactions of Central Asian Islamic architecture with local traditional styles as the Sultanate’s dynasties built their tombs planned around the octagonalized square floorplans of the Baghdadi Muthamman architectural style. Sultanate period tombs still survive at many sites along the modern G.T. road, notably in the Mughal tomb-dominated area of Sikandra in Agra, Uttar Pradesh, where the skeletal remains of a Lodi-era tomb dating to 1517-1526 C.E. can be found to the right of the visitors entrance and ticket stand of the Tomb of Akbar. Better preserved examples of these first forays into Indo-Islamic architecture can be experienced in Delhi’s verdant Lodi gardens, which contains Sikander Lodi’s own tomb. This tomb was the first in India to be enclosed by gardens rather than walls, crowned with turrets and a double-walled onion dome that would become emblematic of the later Mughal architecture style. One of the few remains of a Lodhi-era Mehmam Kama, or sarai, sits at the eastern end of the courtyard containing arched apartments built in a square around the tomb and its gardens.

Bibliography

Chandra, Satish. 2007. History of Medieval India: 800-1700. New Delhi, India: Orient Longman.

Dar, S. R. 2000. “Caravansarais Along the Grand Trunk Road in Pakistan.” In The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce, 158-178. Paris: UNESCO Publishing/Berghahn Books.

Elliot, Henry Miers. 2013. The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Islam, Arshad. 2016. “The Mongol Invasions of Central Asia.” International Journal of Social Science and Humanity 6, no. 4: 315.

Lal, K. S. 1957. “Timur’s Visitation of Delhi.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 20: 197–203. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44304463.

Parihar, Subhash. 2008. Land Transport in Mughal India: Agra-Lahore Mughal Highway and Its Architectural Remains. 8.

- Rathod, Aditya Singh. 2020. “Lodi Garden—A Historical Detour.” International Journal of Research in Humanities & Social Sciences 8 (6): 29. ISSN (P) 2347-5404, ISSN (O) 2320-771X.