Timeline of the Grand Trunk Road

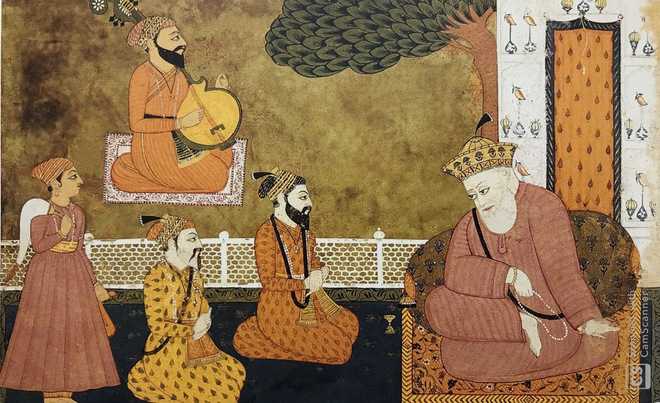

Meet the Mughals: A Timeline of the Mughal Era’s Leaders

The Mughal Period (1526-1857 C.E.)

The Mughals’ greatest enduring achievement as rulers of Northern India would not be their conquest of most of the subcontinent or the mind-boggling wealth of an empire that made up over a quarter of the entire world’s economy, but rather architectural projects that have shaped the international conception of modern-day India. Across the world, the image of India’s architecture is imbued with a distinctly foreign Central Asian, Persian, and Islamic lens that originates in the Mughal’s Turco-Mongol Timurid ancestry.

The Mughal emperors descended upon the continent as conquerors, much like their ancestors Genghis Khan and Timur the Great did. However, they eschewed the extractive policies and conquests of Tamerlane and instead devoted the brunt of their efforts to the prosperity and infrastructure of the new empire. The dynasty was briefly unseated by the Afghan-Bihari leader Sher Shah Suri of the Suri empire, who dethroned emperor Humayun in 1540. Still, Sher Shah’s initiatives on the Uttarapatha would be so comprehensive that today, people still refer to the GT road as the Sher Shah Suri road. After 15 years in Safavid Persia, Humayun re-established control in Delhi with a new love of Safavid Persia’s architecture and government. Humayun and his descendants would go on to build extensively and reigned as the most dominant force in the subcontinent until the death of Shah Alam in 1712.

To more efficiently provide an overview of the Mughal era’s rulers, their architecture, and their impact on the GT road, this exhibition features a timeline of the emperors from Barbur, the founder of the dynasty, to Aurangzeb, who saw the last of the glory days of the Mughal empire. Those interested in the various Mughal sites on the GT road and their architectural and artistic typology are welcome to view the sections dedicated to tombs, caravanserais, kos minars, gardens, and stepwells.

Barbur- (1526-1530 C.E.)

Born in the Fergana Valley of modern-day Uzbekistan to descendents of Genghis Khan and Timur the Great, Barbur ascended to his father’s position as ruler of the Valley at 12 years old before eventually being ousted from his homeland in 1501 by the emerging Khanate of Bukhara. After forming partnerships with the Ottoman and Safavid empires, Barbur would take Kabul in 1504 before defeating the Sultanate of Delhi in 1526 at the battle of Panipat. As the first member of the Mughal Dynasty, Barbur’s reign was marked by territorial expansion and an appreciation for tolerance, art, and culture as he aged. Barbur’s affinity for the gardens and architecture of his homeland would lead to the construction of many projects, of which only a few remain. Along the Agra-Lahore route, Barbur-era sites can still be visited in the Mosque of Kabuli Bagh and the gardens of Ram Bagh in Agra. Barbur also invested in the road itself, building 11-meter/36-foot high Kos Minars every nine kos from Agra to Kabul.

Sher Shah Suri and the Sur Dynasty- (1540-1555 C.E.)

After ousting a young Emperor Humayun, the Afghan-Bihari ruler Sher Shah Suri focused a good portion of his policy on the Uttarapatha, revitalizing the route to such an extent that today, the GT road is still sometimes called the Sher Shah Suri road. Under Suri, the route’s path was set and widened from Songaron, Bengal, to the Indus River valley in Pakistan. Along the newly upgraded Road, trees were planted along the sides to provide food and shade, Kos Minars and Stepwells were placed at more frequent intervals along the route, and a total of 1,700 Caravansarais with free food and lodging to house travelers and traders. Following Sher Shah’s death in 1545, his son Islam Shah would ascend the throne and continue his father’s policy, building another Sarai between each erected by his father. Following Islam Shah’s rule death in 1554, the Sur empire fell into decline and eventually lost its territory to the returning Mughal rulers.

Humayun- (1530-1540 C.E., 1555-1556 C.E.)

The second Mughal emperor, Humayun, was inexperienced when he first came to the throne as a young adult in 1530. The young ruler lost his kingdom and was temporarily exiled to Safavid Persia during the rule of Sher Shah Suri. During his fifteen-year stay, Humayun became so enamored with the Timurid-inspired Persian culture that he brought it back to India, just as Peter the Great and Thomas Jefferson brought French culture back to Russia and the United States. Humayun’s affinity for Persian culture led to an increase in Persian art, design, and architecture in the years following his reign. After regaining his territory from the collapsing Sur empire, Humayun quickly expanded the empire before dying after falling down the stairs less than a year after regaining his kingdom.

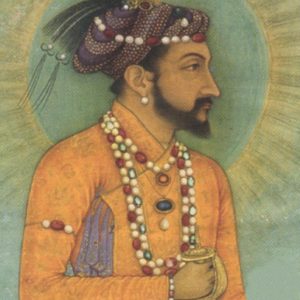

Akbar the Great (1556-1605 C.E.)

Akbar is remembered as one of India’s greatest rulers, known today for his policies that centralized and reformed administration, increased tolerance and secularization in his domain, and tripled the empire’s economy. The new wealth secured by Akbar allowed for expansive projects across the empire, notably on the Grand Trunk Road, where he constructed more Sarais and ordered nobles to do likewise. Kos Minars were similarly erected along the empire’s highways, often adorned with hundreds of deer antlers to showcase Akbar’s affinity for hunting. His newly-built court at Fatehpur Sikri in Uttar Pradesh became a center of tolerance, inviting European Christian missionaries, Hindus, Muslims, and Parsis to have religious discussions in the Emperor’s presence. These exchanges lead to elements from their native art and culture being used in Mughal works, with features like European realism in painting applied to the more vivid Mughal painting style

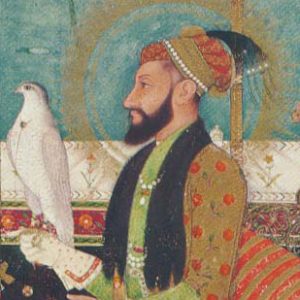

Jahangir (1605-1627 C.E.)

Jahangir’s reign was marked by the emperors’ affinity for art and culture, due to an increased patronage of the arts that enabled the flourishing of the Mughal art style. While art and architecture would reach some of its highest points in this period, Jahangir’s proclivity towards alcohol and opium led to the Emperor having weak control of his courts. Still, the Agra-Lahore would be a central focus for Jahangir, who ordered that the wealth of all who died without an heir would be seized by the state and spent on the construction of mosques, sarais, bridges, and stepwells. Landowners in more dangerous corners of the empire were ordered to construct these buildings and encourage settlement around them. Sarai construction was also greatly improved, as Jahangir ordered their construction to be made from brick instead of the Mud used in previous sarais. Similarly, Kos Minars were erected every kos between Agra and Delhi.

Shah Jahan (1628-1658 C.E.)

Shah Jahan’s time as ruler of the Mughals is characterized by the empire’s expansion to new frontiers and the construction of grand monuments like the Taj Mahal, Moti Masjid, and Red Fort. Jahan’s affinity for white marble is demonstrated in his projects, which feature the extensive use of the stone in constructions known today as the zenith of the Mughal style. The Emperor’s love of construction extended into the empire’s highways, which saw new Sarais, bridges, and roads built to connect his empire, albeit on a smaller scale than his father Jahangir’s policies.

Aurangzeb (1659-1707 C.E.)

Aurangzeb was the last of the great Mughal rulers, distinguished by his devout piety to Muslim tradition and military aptitude. After defeating his older brother in a war of succession and imprisoning his father in Agra Fort, Aurangzeb extended the territory to it’s greatest extent. Aurangzeb’s piety led to larger divisions between the Hindu and Muslim members of his empire, and his expensive conquests bankrupted the Mughals, leading to a period of decline following his death in 1707. Still, Aurangzeb invested into the royal road system: realizing that large stretches of the empire still lacked sarais and the safety they provided, Aurangzeb ordered the construction of sarais with a bazaar, mosque, well, and bathouse in these regions. In addition, Aurangzeb provided these waystations with attendants and craftsmen, and restored those that were decaying.

Bibliography

Ballhatchet, K. A. “Akbar.” Encyclopedia Britannica, July 29, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Akbar.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Humāyūn.” Encyclopedia Britannica, August 1, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Humayun-Mughal-emperor.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Shah Jahān.” Encyclopedia Britannica, August 3, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jahangir.

Dar, S. R. 2000. “Caravansarais Along the Grand Trunk Road in Pakistan.” In The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce, 158-178. Paris: UNESCO Publishing/Berghann Books.

Spear, T. Percival. “Aurangzeb.” Encyclopedia Britannica, August 5, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Aurangzeb.

Spear, T. Percival. “Bābur.” Encyclopedia Britannica, July 22, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Babur.