Mughal Architecture along the GT Road

Tombs

Across cultures, peoples, and landmasses, certain aspects of humanity consistently appear no matter the geographic divide. Of the major concerns shared by all members of our species, it seems that the mystery of death, inevitably followed by “what do we do with the bodies?” has reigned supreme in its’ hold on the public consciousness. This line of thought was further complicated by the emergence of culture and civilization, which extended the discussion and deduced that the act of burial or cremation is simply not enough and that bigger does, in fact, mean better. Eventually, this now culture-defining line of thought was extended to almost absurd levels by some variation of “Hey, wouldn’t that big sand dune look way better if there was a massive triangle with my corpse and earthly possessions inside it?” as the pharaohs did in Egypt. Needless to say, tombs’ functionality far extends their material, in that they become an incredibly human expression of not only our conceptions of death and the afterlife, but also a tangible expression of a ruler’s power, a merchant’s wealth, or the beauty of a lost love. Today, Mughal tombs remain as some of the best preserved and most magnificent examples of what Mughal architecture looked like both within their cities and along the Royal Highway network.

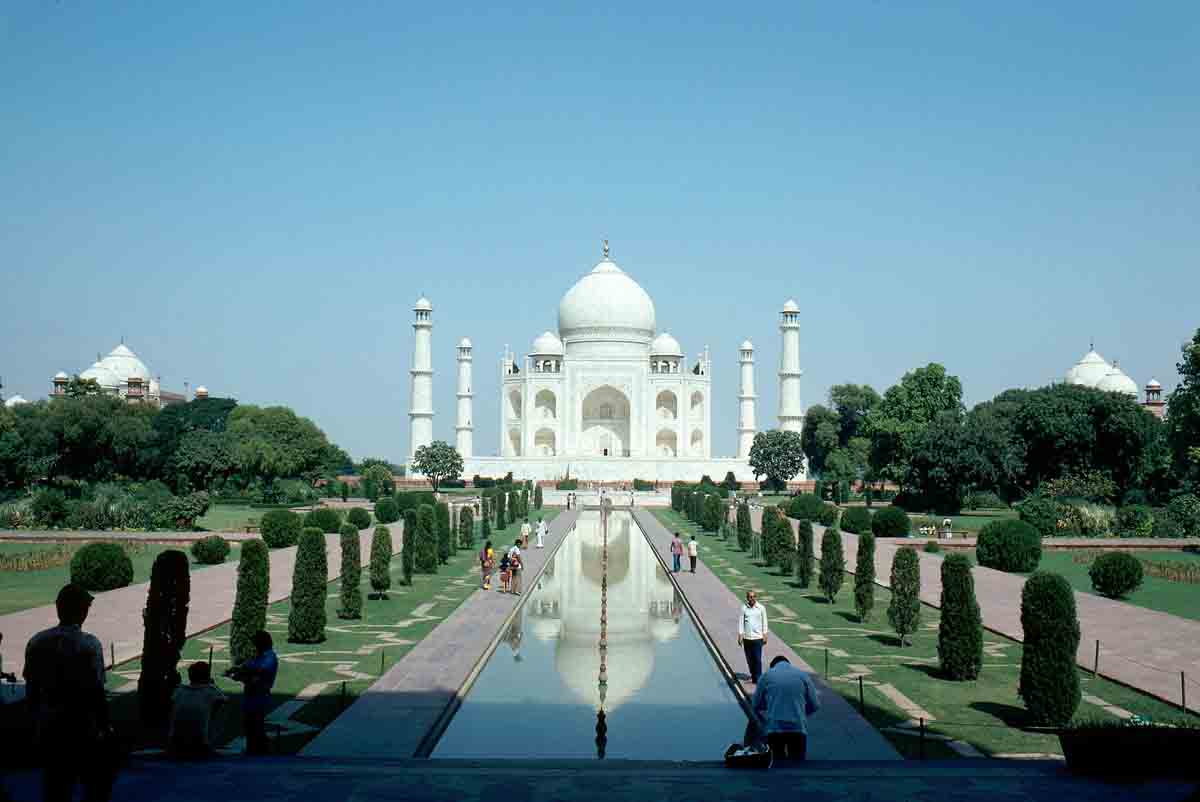

Arguably the three most famous tombs in the world today: Giza’s Great Pyramids, Xi’an’s Terracotta Army, and Agra’s Taj Mahal

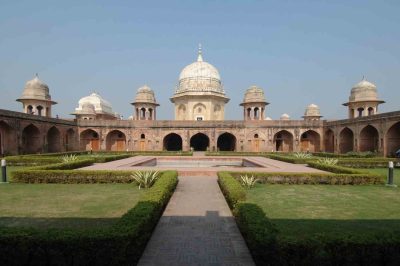

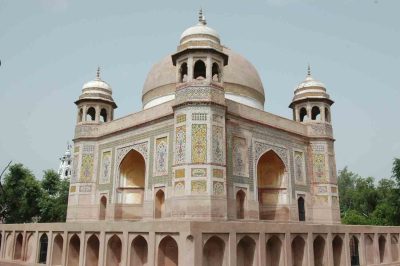

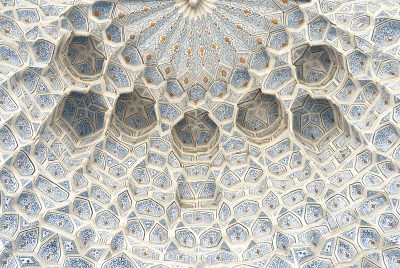

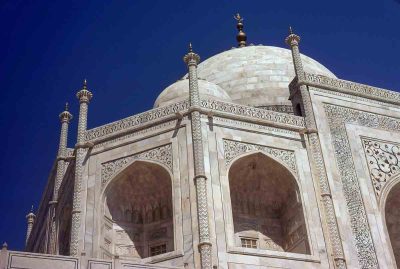

While the Mughals did not construct the first tombs in India, they almost certainly perfected it. The dynasty has not been made immortal in the eyes of the world due to military or administrative accomplishments, but rather the construction of architectural marvels like Humayun’s tomb in Delhi. Mughal tombs exalt the power of their builders by quite literally putting the memorial on a podium crowned with massive buildings that even in the medieval era created skylines across the empire’s cities. These tombs feature massive vaulted roofs and onion-domes decorated with lavish Indo-Islamic ornamentation in the form of carvings, tile work, and frescos depicting calligraphy, geography, and nature. These complexes are then surrounded by verdant charbagh-style gardens designed to emulate the Islamic conception of heaven within their very funeral complexes.

Inspired by their Central Asian ancestor Timur the Great’s public projects, and a deep love of Safavid Iran’s culture and architecture, the Mughals would mix local craftsmanship and materials with their tastes to encapsulate an increasingly multi-cultural background. This, combined with their royal status, resulted in grand presentations of power and wealth that captivate the visitor. Remarkably, it is not the tomb of a great ruler of this dynasty like Akbar the Great or even its’ founder, Barbur, that has become the most widely-recognized ambassador of both the Mughals and India, but rather one dedicated to the undying love for the Mughal ruler Shah Jahan’s favorite wife: the Taj Mahal in Agra. The monolith acts as a jewel in the crown of India, quite deservedly earning a designation as one of the modern wonders of the world by showcasing the zenith of Mughal construction and wealth in humankind’s magnum opus of the representation of grief.

Investing what would today be tens of billions of dollars into any public project, particularly a tomb for auspicious individuals, inherently makes the geographic setting of the construction an essential aspect of its development. The Mughal period’s focus on the development of their Badshai Sadak (later called the GT road), in particular the stretch connecting the historic capitals of Lahore, Delhi, and Agra, presented the perfect environment to showcase their architectural prowess on the busiest and most cosmopolitan stretch of their empire. While the most prominent sites like the Taj Mahal, Humayun’s tomb, and the tomb of Jahangir are located within these capitals in Agra, Delhi, and Lahore, respectively, the entirety of the Agra-Lahore highway is littered with awe-inspiring memorials built along the same architectural styles for influential figures of the era.

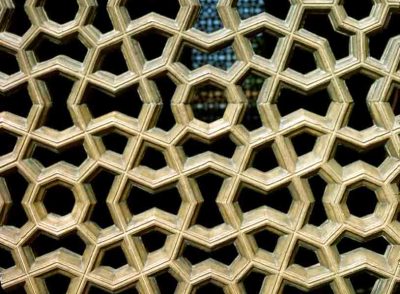

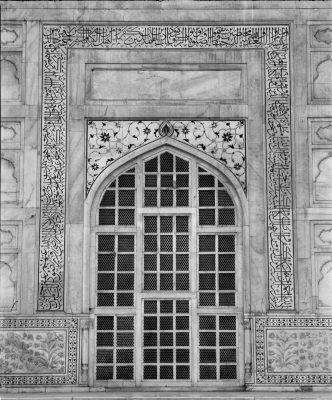

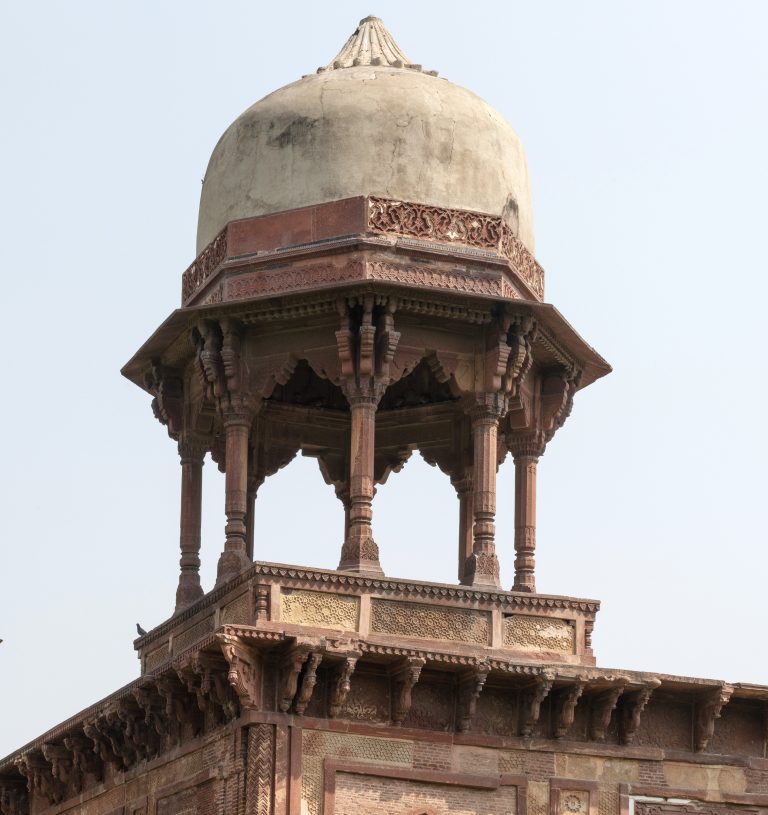

Whether one wishes to see raised podiums, the iconic octagonal onion domes, geometrically-carved marble screens, chhatri bastions and minarets, Persian tilework, or Mughal motifs, even the most rural stretches of the Agra-Lahore road offer a comprehensive overview of Mughal funerary architecture at on an intimate scale at sites like Sheik Chilli’s tomb in Kurukshetra, Haryana, the tombs of Ustad and Shagird in Sirhind-Fategarh, Punjab, the tombs of Muhammad Modin and Haji Jamal in Nakodar, Punjab, or at dozens of other memorials along the Mughal empire’s main artery.

An Architectural Overview of Mughal Tombs

The confluence of cultures that shaped Mughal architecture is best exemplified in Humayun’s tomb, a 16th-century UNESCO World Heritage site that houses the remains of Mughal emperor Humayun and his family. Humayun’s tomb showcases the cultural origin of Mughal architecture: the structure seems heavily inspired by Gur-i-Amir, the mausoleum of Timur the Great in Samarqand, Uzbekistan, with its’ radially symmetrical octagonal layout and massive double-walled bulbous “onion dome” showcasing the Mughal’s Timurid roots. This call to their ancestors would be fused with local Indian traditions, seen in the tomb’s carved red sandstone exterior, and Islamic ones, demonstrated in extensive Indo-Islamic motifs and a sunlight-illuminated marble prayer shade (called a Mihrab) facing towards Mecca. The presence of decorated tiles and squinches as a dome support across Mughal architecture further harkens back to the dynasty’s roots.

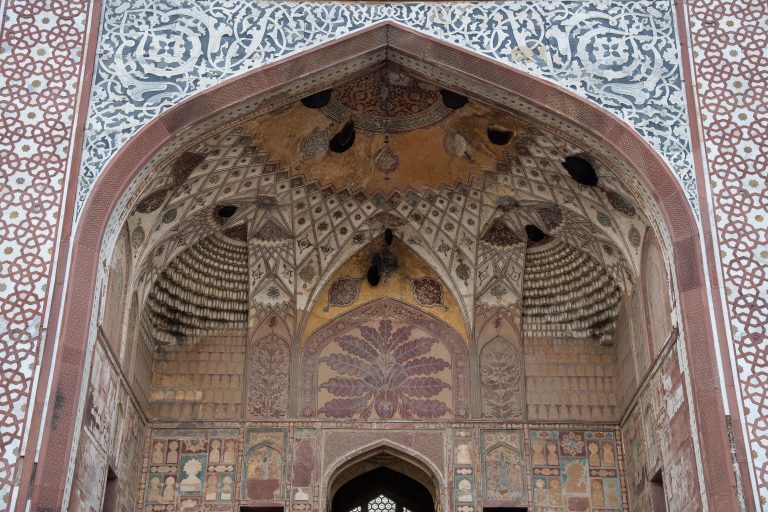

The very layout of the tomb itself is distinctly Persian, designed with eight rooms around a central hall in a style called Hasht-behest, designed to emulate the Abrahamic conception of heaven’s eight spaces and the astrological belief of eight planets in the heavens. Perhaps the most defining feature of Mughal tombs that originates from the Timurids is the presence of a massive podium called a takhtgah underneath the main structure. These podiums feature elaborately decorated entryways called pishtaqs, vaulted bays, and extensive frescos that elevate these already grand monuments to new heights. The whole structure would then be surrounded by or placed behind rich Mughal-style gardens, usually enclosed again by a large wall with gatehouses, or Iwans, adorned with more floral, geometric, and calligraphic tile work and painting.

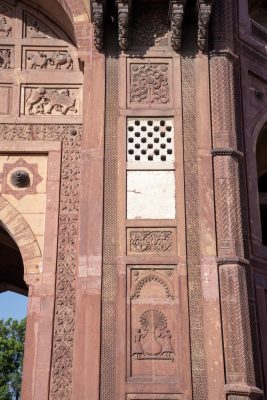

South Iwan of Akbar’s Tomb, Sikandra, Agra, India, 1605-1613 CE, Structural; red sandstone with white and black marble AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF INDIAN STUDIES/CENTER FOR SOUTH ASIAN ART & ARCHAEOLOGY, 0451

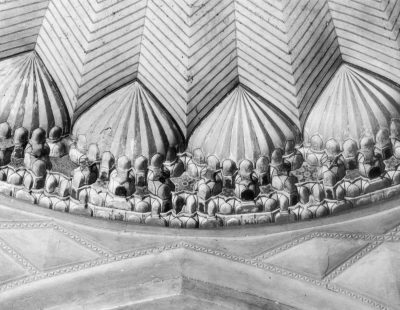

The form of Mughal tombs would evolve extensively over the dynasty’s 331-year rule of India. Jahangir’s reign would witness an architectural shift that revolutionized the Mughal architectural style, particularly evident in Akbar’s tomb in Sikandra, Agra. The tomb’s open marble top floor, octagonal minaret-adorned complex and gatehouse, and prominently featured, lavishly carved stone wall panels set a new precedent for future tombs and projects. The most noticeable change in this structure from the Timurid roots of Mughal architecture is the lack of the large, double-walled exterior domes that defined both Humayun and Tamerlane’s mausoleums, an indicator of a resurgence in the popularity of Hindu design elements during Akbar’s time.

The Mughal style would reach its pinnacle under Shah Jahan, whose reign would see the destruction and remodification of many previously built projects to beautify his realm, and the creation of India’s most captivating landmark: the Taj Mahal. Shah Jahan’s focus on elegance over size compared to his predecessors was only one of a few notable changes in the architectural typology of his era; this evolution saw the shift away from the centralized plan seen in earlier constructions to a mirrored bilateral one that favored a rectangular floorplan. Decoratively, the shift saw the widespread use of multifaceted cusped columns dubbed Shahjahani columns and the introduction of semi-circular arches supported by balusters adorned with European-inspired, three-dimensional botanical carvings and a pot-like base styled after Hindu and Buddhist balusters in East India. The design of these city-adjacent imperial tombs would impact far more than just their immediate geographic setting, as Mughal court members and particularly auspicious individuals would build their own memorials on a smaller scale along the modern GT road, utilizing the breadth of Mughal design and typology.

The Mughals would also reuse and modify pre-existing structures to house their dead, particularly in similarly Indo-Islamic sultanate-era constructions. Perhaps the best example of this can be found near Akbar’s tomb in Sikandra, Agra, where a bardari, or open-air, twelve-doored pavilion from the sultanate period was converted into a tomb in 1627 for Mariam-Uz-Zamani, Akbar’s wife and the mother of Jahangir. Jahangir modified the structure into a tomb that fit within the Mughal architectural style by constructing a crypt beneath the main pavilion and garnishing the outside walls with carved red sandstone panels featuring floral and geometric designs, chhajas (overhangs), and mezzanine floors called Duchaatis at its corners. The floorplan of the tomb after these renovations is square-shaped but centers itself around an octagonal main room surrounded by eight smaller rooms divided by pointed arches. Massive octagonal Chaatris crown the corners of the square building, with intensely detailed supports in place of the large onion dome commonly found on Mughal tombs.

Bibliography

Archaeological Survey of India. The Tomb of Mariam Zamani. Informational Plaque for Tomb of Mariam Zamani. Sikandra, Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India. Viewed August 3, 2024.

Asher, Catherine Blanshard. Architecture of Mughal India. The New Cambridge History of India, Part I, Vol. 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 9780521267281.

Bernardini, Michele. “HAŠT BEHEŠT (2).” Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. XII, March 20, 2012, 49–51.

Koch, E. Mughal Architecture: An Outline of its History and Development (1526-1858). Munich: Prestel, 1991.

Lowry, Glenn D. “Humayun’s Tomb: Form, Function, and Meaning in Early Mughal Architecture.” Muqarnas 4 (1987): 133–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/1523100.

Parihar, Subhash. “Travelling with the Mughals: A Survey of the Agra-Lahore Highway.” Marg 60, no. 4 (2009).

Petersen, Andrew. Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. London: Routledge, 1996.

Sinha, Vandana. “Documentation of Indo-Islamic Architecture Built Along a 16th-century Highway.” Art Libraries Journal 44, no. 3 (2019): 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1017/alj.2019.14.