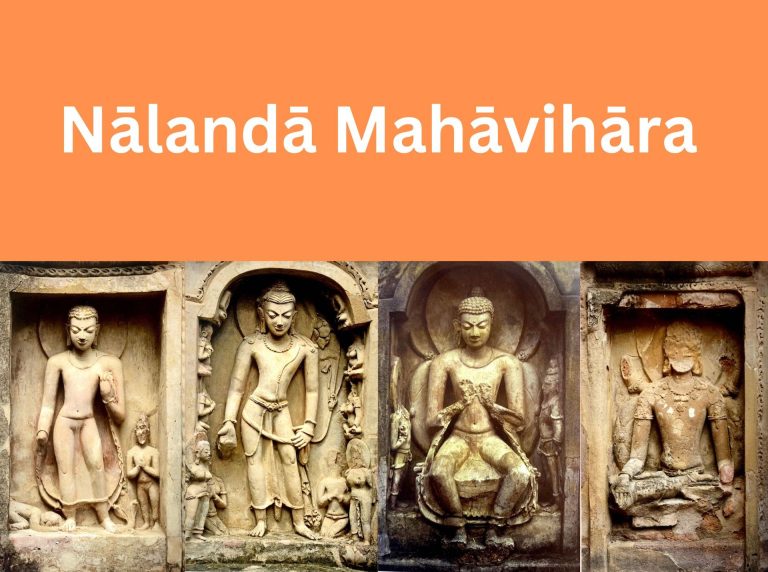

Changing Iconography,

Changing Identity

Images of Uma in Chola Bronze Sculpture

Worshippers in the Chola kingdom believed in three Puranic gods: Shiva, Vishnu and the Devi. As the great goddess or Shakti, even today, Devi’s devotees believe in the supreme power of the female image, leaving the male counterpart in a subsidiary position. The Devi is worshipped as the all-creating, all-preserving, and all-destroying deity. She has thousands of names that reflect local customs and legends. She is one, and she is many. All Hindu goddesses may be viewed as different manifestations of the Devi. In some forms, she is benign and gentle, while in other forms, she is dynamic and fierce, but in all forms, she is Ma or the approachable mother to her devotees. This idea of Shakti also influenced the Shaiva nayanmar and Vaishnava alvar saints during and before the Chola empire. The saints wrote poetry about their respective gods and mentioned their consorts as the Shakti (energy) that accompanied them.

Devi Uma-Parameshwari was widely worshipped as the consort of Shiva during the Chola dynasty. She was celebrated as the bride, wife and mother. In her more fierce forms, Uma’s various manifestations, as seen in Chola bronze sculptures, were Durga, Mahishasuramardini, Nishumbasudani, Kali and Bhadrakali. Artists created various statues for their patrons and worshippers for use in temples and in large public processions during festivals. This exhibition compiles bronze sculptures of Uma as consort and autonomous goddess from Thanjavur district, the heart of the Chola empire during the 10th and 11th centuries. The exhibition focuses of the sculptures as a part of larger stories where artists made the body of the deity with specific ornament, gait, and posture to suggest an attitude appropriate to the narrative.

The Cholas ruled a large area of south India and beyond from the 9th to the 13th centuries Common Era (CE). Royal and elite patronage of the arts showed their devotion and their social and political power. This was not a world in which the sacred was neatly separated from other realms of human endeavour. Great stone temples, sensuous sculptures, literary compilations and dance and music were important ways of worshipping gods and honouring humans.

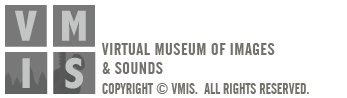

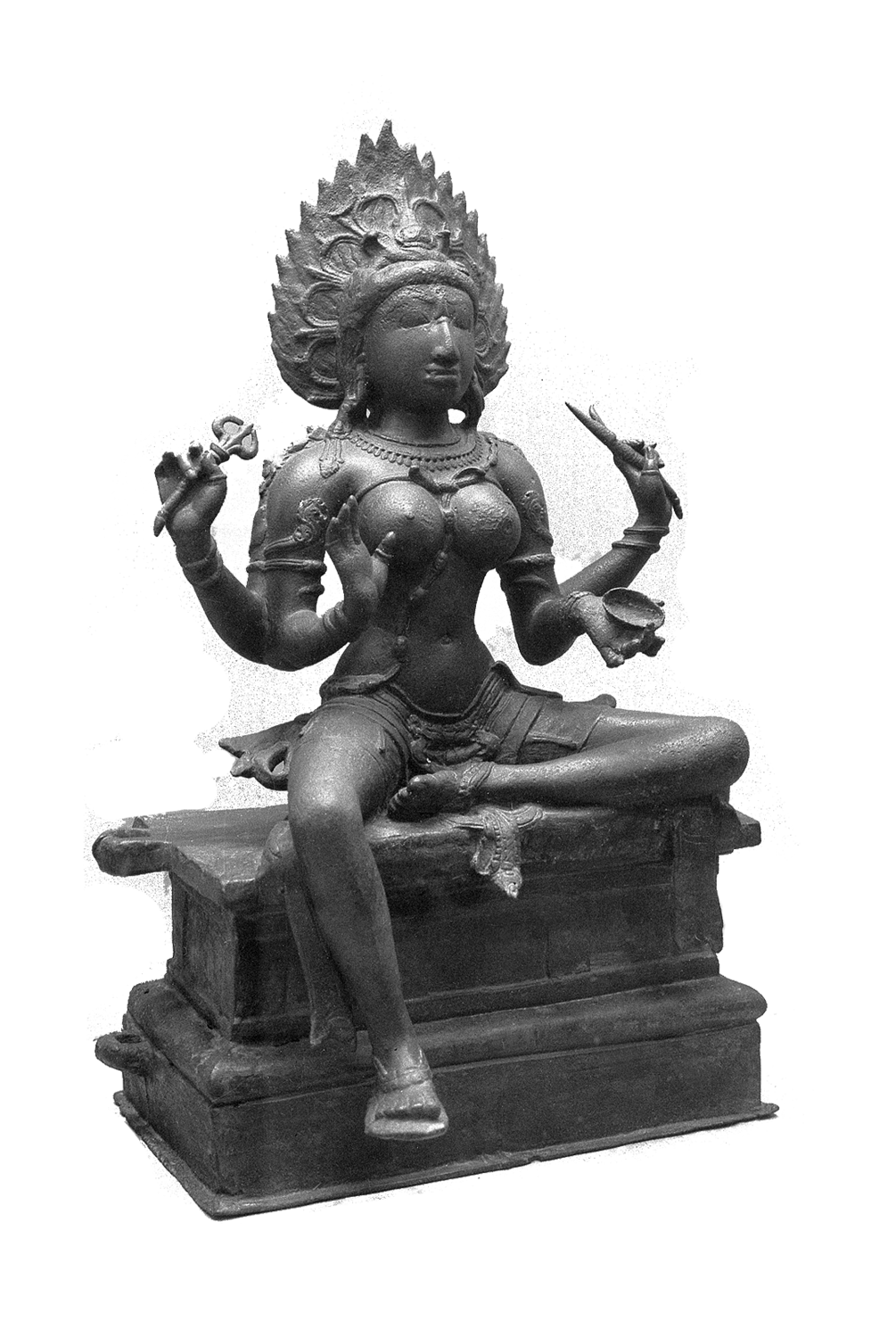

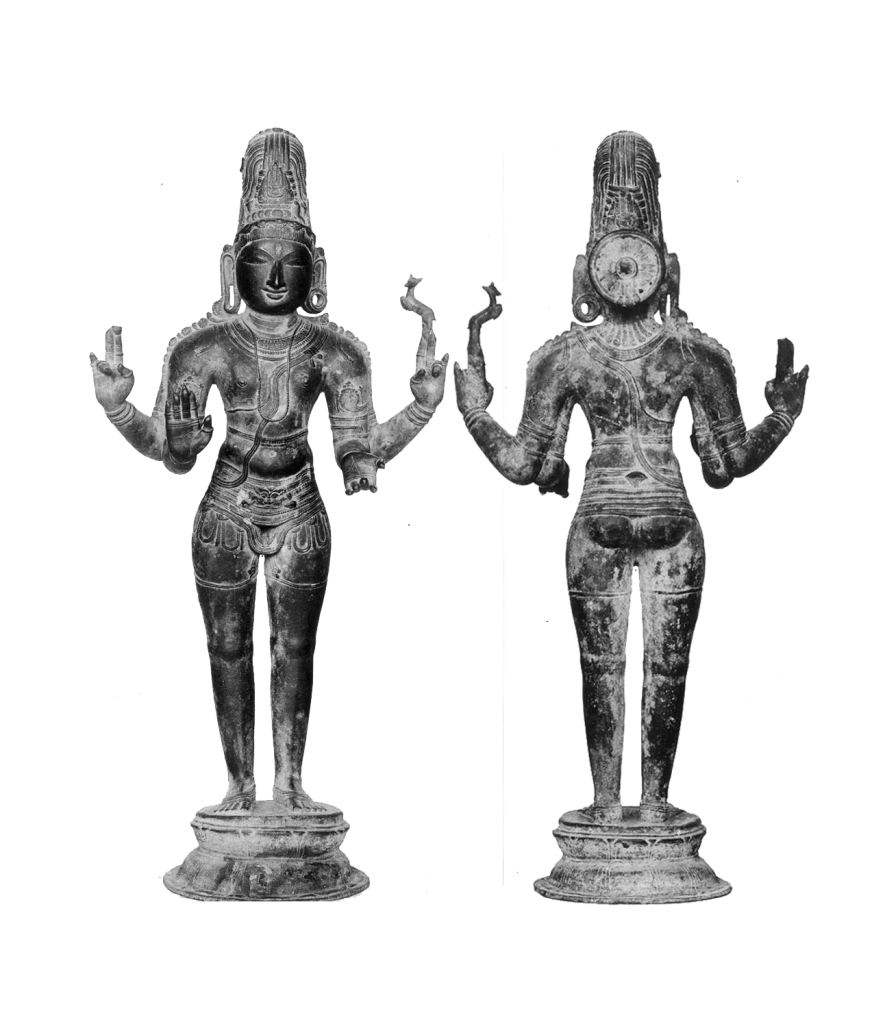

Uma Paramesvari

Tamil Nadu, India

11th Century CE, Chola, Bronze, 63.6 cm (H)

Tanjore Art Gallery

Photo Credit: American Institute of Indian Studies – 9810

Temple bronzes of the period are the most spectacular works of art. During this Chola kingdom, bronze-casting reached a level of excellence. Bronze sculptures curated for this online exhibition were once, and still are, a principal component of Tamil temples. The images of deities and saints were created as objects of worship and were once adorned with silks, jewelry, and floral decorations that covered them almost completely when worshipped in processions. In the Chola kingdom, immovable deities made in stone installed in the sanctum according to prescribed rituals as well as bronze portable and even earlier wood images (utsavamurtis) used as procession images for festivals still continue to be decorated for worship. These sculptures were living deities, not just art objects. Devotees came to them with their fears and desires as well as gratitude. However, when these statues are collected, they are exhibited as works of art and, like in this exhibition, displayed in their unadorned state.

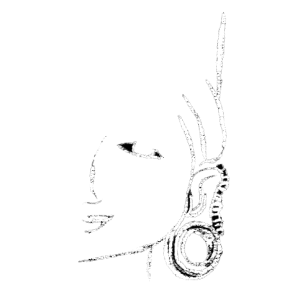

Uma-Parameshwari

kataka-hasta:

Symbolic hand gesture with the tips of the fingers joined to. the thumb to form a ring; a fresh or bronze lotus or blue lily blossom is inserted.

karanda-mukuta:

Conical crown studded with jewels. Here, with flowing jatas (matted locks of hair) rolling over the nape and neck.

Trivali tarangini:

Three lines along the ribcage considered sign of beauty. A woman with this attribute was applauded in poetry as “Trivali tarangini”

Also, seen a Brahminical sacred thread flowing from left to right of Uma’s bodice.

Devotees of Uma- Parameshwari understands her as a personification of supreme feminine power. She is depicted as a voluptuous woman with an exquisite body. In the Chola kingdom, her iconography is relatively consistent. She stands in a graceful tribhanga (triple bend) posture, with her right hand raised to hold a lotus or blue lily blossom (could be real or out of bronze), while her other hand gracefully contours her body.

The sculptors produced timeless images of the goddess. Her body, tall and sleek reveals the Goddess’ extraordinary beauty and perfection with her gently rounded breasts, slender torso, and fuller hips to heighten awareness of the form and a swaying sense of movement. In the two bronzes, Uma adorns karanda-mukuta (conical crown), pierced plate ear-ornament, stacks of necklaces, a Brahminical thread, elaborate armlets (pottu and vajibandha), elbow band, cluster of bangles, rings on all fingers and anklets.

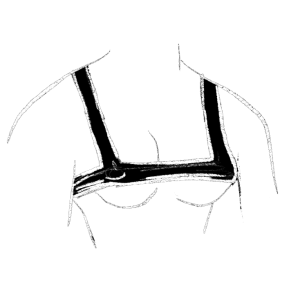

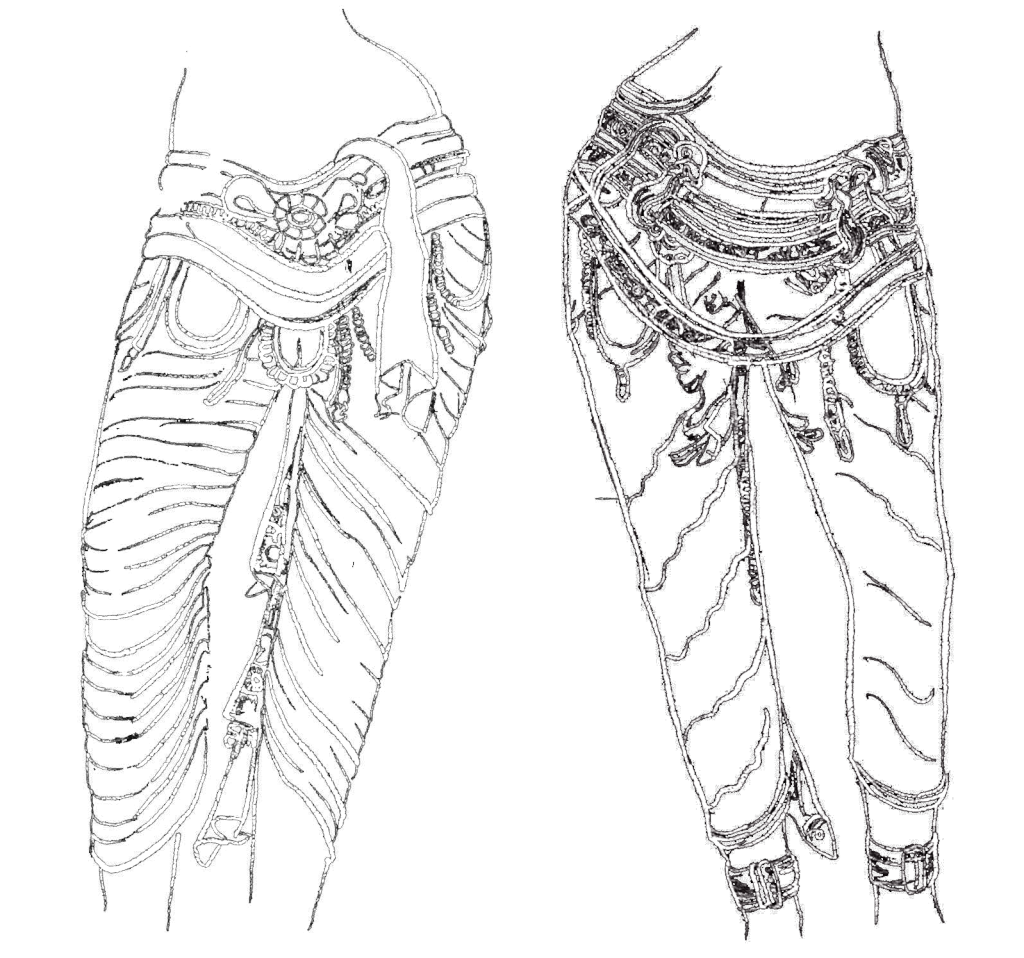

Starting way below her navel, the fabric is draped with pleats around Uma’s legs, held together by decorative clasps and beautiful ornate belts. The two sculptures show different ways of portraying pleats. The below sketch elaborates on the drapery and waist jewellery.

Uma

Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, India

10th Century CE, Chola, Bronze, 91.4 cm (H)

Tanjore Art Gallery

Photo Credit: American Institute of Indian Studies – 10410

Uma,

Tamil Nadu, India

11th Century CE, Chola, Bronze, 63.6 cm (H)

Tanjore Art Gallery

Photo Credit: American Institute of Indian Studies – 9810

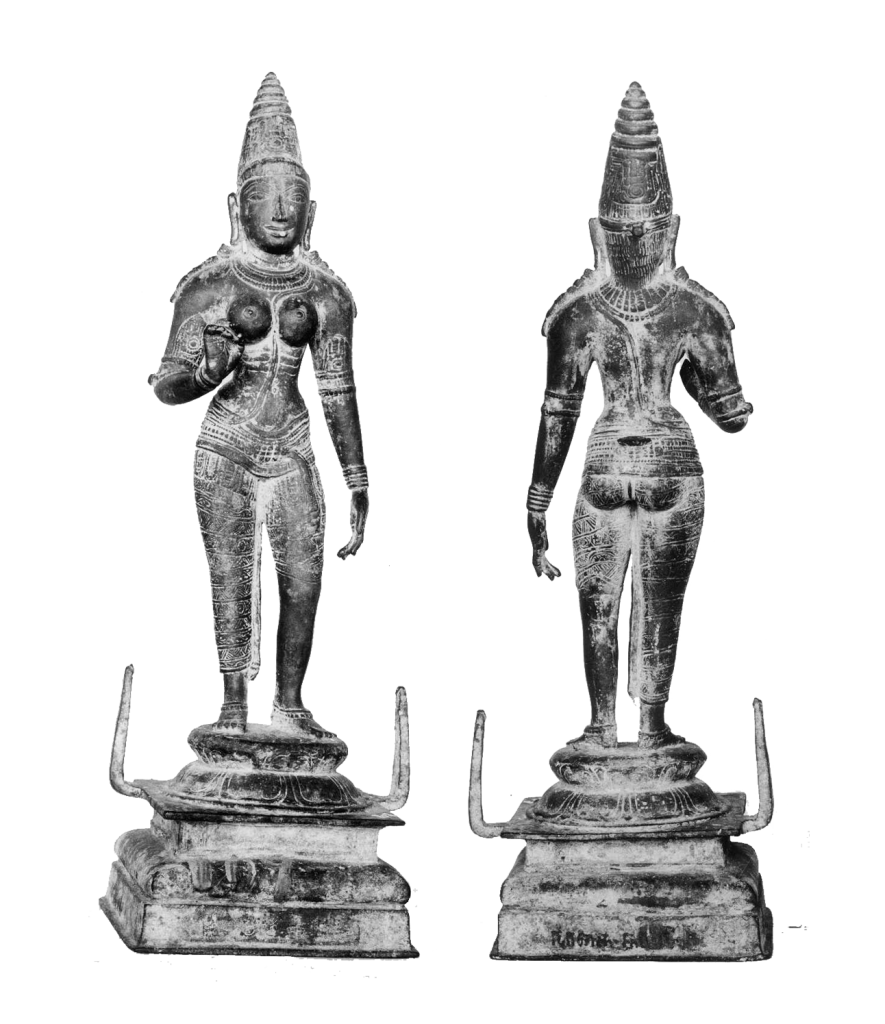

Kalyanasundara Murtis (Marriage Sculptures)

In regards to iconography, the sculptors present the wedding ceremony of Uma and Shiva in two separate episodes,

panigrahana, ritual in presence of fire, where the groom takes the bride’s hand as a sign of their union and

saptapadi, circumambulating the holy fire which bears witness in a Vedic marriage.

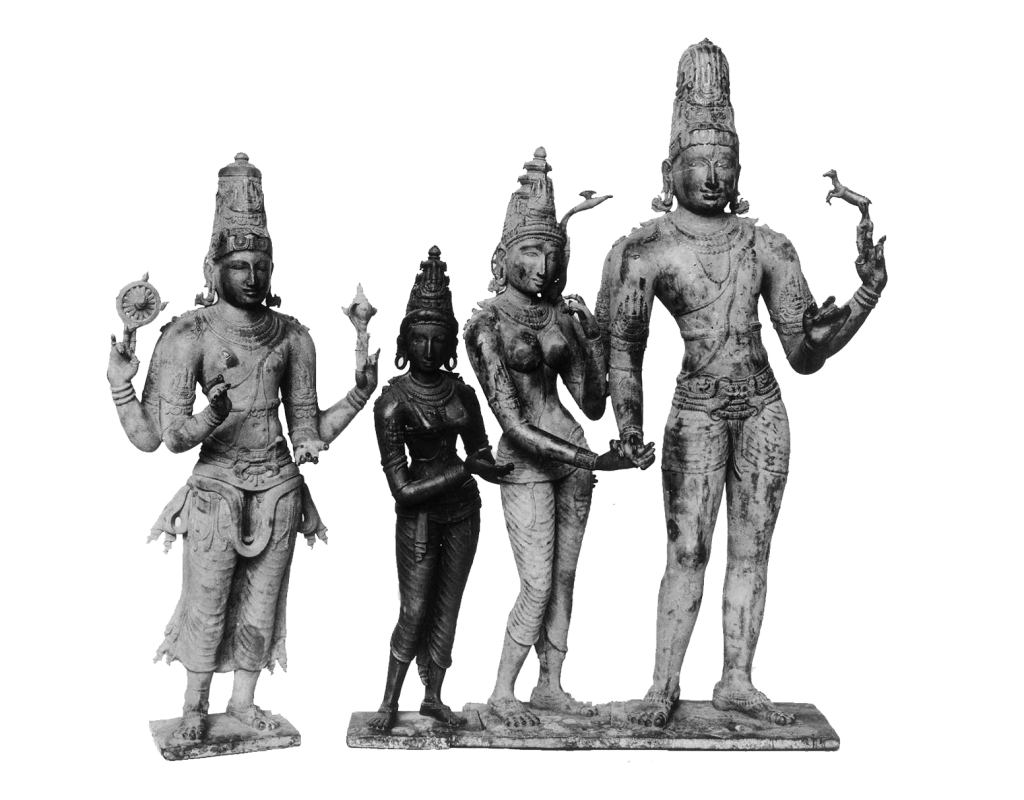

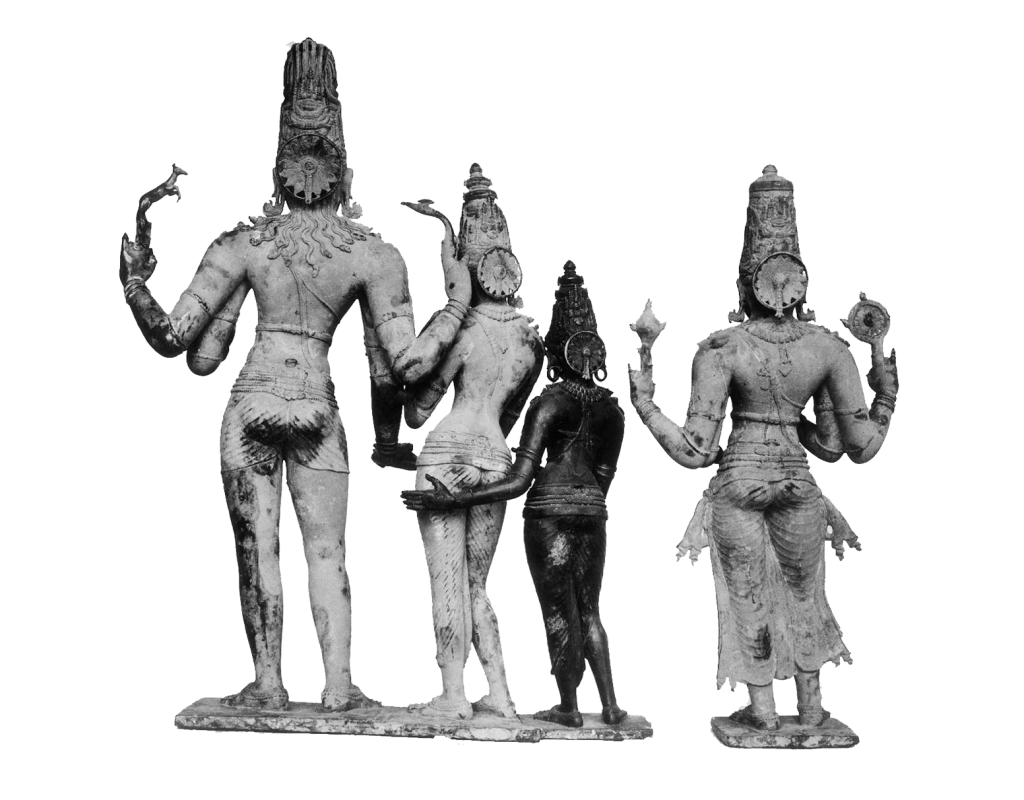

Panigrahana Ceremony

In the composition Shiva, as the bridegroom, is represented as taking his bride Uma’s hand. The ceremony also includes Vishnu and Lakshmi. Some research suggests Vishnu and Lakshmi as parents giving away the bride or Vishnu as the brother and Lakshmi as the bride’s friend.

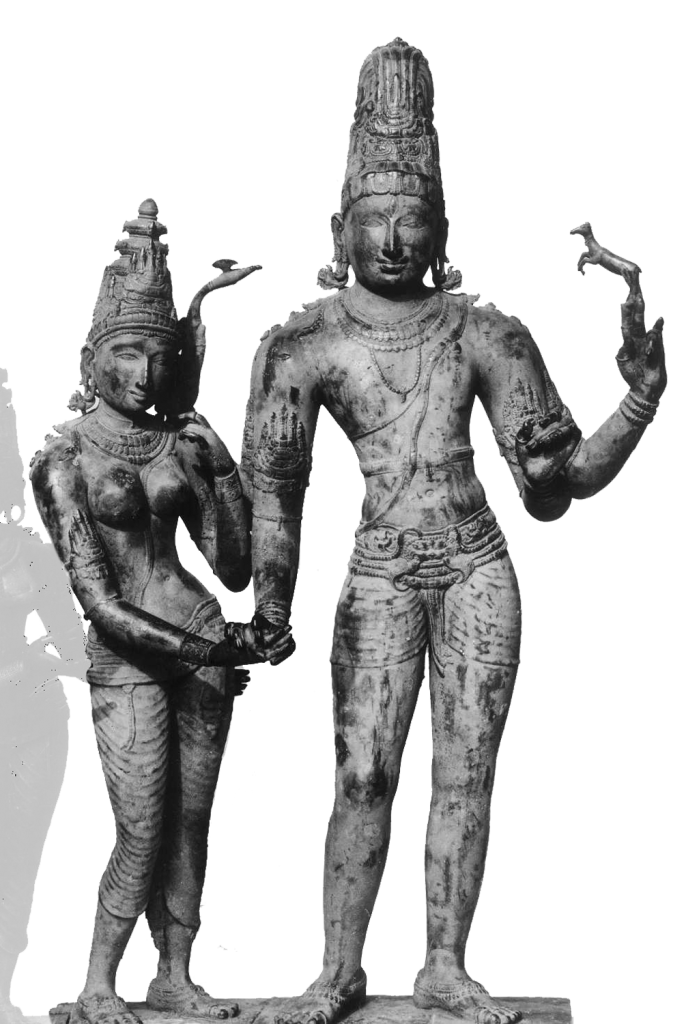

Marriage of Shiva and Uma (Kalyanasundara – Panigrahana ceremony),

Tiruvenkadu Temple, Tanjavur District, Tamil Nadu, India

11th Century, Chola, Bronze, 96.6 cm (H)

Tanjore Art Gallery

Photo Credit: American Institute of Indian Studies – 11857, 22527

Detail from Marriage of Shiva and Uma (Kalyanasundara – Panigrahana ceremony)

The master sculptor portrays Uma as very young. Her head is bent down in shyness as she leans away out of a sense of decency. Timidly, she stands a few steps behind Shiva and reaches his eyes. Her shoulders are tilted inwards just a little, giving the bridegroom authority. Uma’s left hand is positioned to hold the flower, and her right is stretched out for the ceremony. This panigrahana ceremony exists till today.

Uma is richly adorned in her jewellery. Young Shiva, the bridegroom is poised yet relaxed with his hair piled high on his head under the diadem. He wears a series of necklaces, makara (mythical aquatic) earrings, Brahmanical sacred thread, draped dhoti, and jewellery. He stand in a triple-bent stance and reaches out his right hand to take his bride Uma’s right hand. Shiva’s other front hand is in varda (hand pose of bestowing boons) while the back two hold parasu (axe) on right and mega (deer) on left.

Vishnu

Details from Marriage Tableau

Lakshmi, Shiva and Uma stand on one pedestal, and Vishnu stands separately. Vishnu holds his attributes— discus on the right and conch shell on the left—in two rear hands. The right front hand is raised in the gesture of protection while the other is raised to maybe hold the golden pot of water, ready to pour it in the ceremony of giving the bride to the bridegroom. He is wearing a tall crown and abundant jewellery, and is accompanied by his wife Lakshmi, goddess of wealth and fortune, for the ceremony.

Laksmi stands further away from Vishnu. For the ceremony, some suggest her as the mother and others as the confidante of Uma. Like a true friend, Laksmi uses both hands to urge the shy bride towards Shiva gently. Standing in tribhanga pose, Laksmi is also richly adorned for the wedding ceremony.

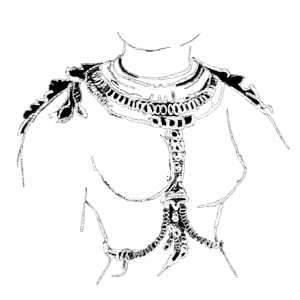

Some details of Lakshmi’s jewelry:

Lakshmi

Details from Marriage Tableau

Saptapadi Ceremony

As depicted in sculptures, the other marriage ceremony is saptapadi—the ritual of circumambulating the fire. Uma has her right knee bent and stands facing Shiva. Shiva, too is flexed in tribhanga pose with his left knee bent and is simultaneously reaching out his right hand to grasp Uma’s right hand. Unlike other examples of the couple looking forward directly at the devotee, this composition illustrates them as walking.

The ritual of circumambulating the fire is the most important in a Hindu marriage ceremony. ‘Sapta‘ means seven, and ‘Padi’ means steps. It means when the couple takes seven steps around the holy fire or Agni Kundam, only then do they become husband and wife.

Shiva and Uma, Saptapadi ritual

Tirumananjeri, Thanjavur District, Tamil Nadu, India

10th Century, Chola, Bronze

Photo Credit: Donaldson, Thomas Eugene. Síva-Pārvatī and Allied Images: Their Iconography and Body Language. 1. Vol. 2. 2 vols. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld, 2007.

Copyright: French Institute of Pondicherry/ Ecole Francaise d’Extreme-Orient; neg. IFI 597-10)

Shiva and Uma, Saptapadi ritual

Tiruvelvikkudi, Thanjavur District, Tamil Nadu, India

11th Century, Chola, Bronze

Photo Credit: Donaldson, Thomas Eugene. Síva-Pārvatī and Allied Images: Their Iconography and Body Language. 1. Vol. 2. 2 vols. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld, 2007.

Copyright: French Institute of Pondicherry/ Ecole Francaise d’Extreme-Orient; neg. IFI 1397-8)

A wide range of Shiva manifestations and iconographies developed before and during the Chola period, each of them with its own meaning and story behind it. However, for temple ritual purposes, according to Shaiva Siddhantha, Shiva could only bestow his grace on an individual soul when in the company of Uma-Parameshwari.

Uma, as the beautiful consort, the dutiful wife and mother of Ganesha and Skanda, accompanied her husband. When paired together, Shiva and Uma’s physical and emotional interactions, as displayed in their posture, become the key themes of the sculptures.

Shiva has specific iconography and posture for each of his manifestations, but his consort Uma is most often shown in tribhanga (triple bend) posture. When with Shiva, Uma always has only two hands, right raised to hold a lotus or blue lily blossom (could have been real or made of bronze), while the other gracefully contours her side. The sculptor captured her stilled movement in tribhanga and this posture became a standard way for sculptors to render her sensuous and captivating beauty. The pose expressed poise and enhanced the lithe femininity of her figure. They accentuated the Goddess’ slender body with rounded breasts, narrow waist, and gently curved hip.

Tamil nayanmar saint in sacred hymns use sensual language to describe the great beauty of Shiva’s wife. A verse from Saint Sundarar (ca. 800) poem is an example to show how Uma was described in hymns written about Shiva. Even before the poem, it’s important to mention that the sensual language was considered appropriate by the poets of the time who innocently only saw the divine aura of the beautiful goddess. In the example, each verse commences “Shiva passed this way” and was followed by reference to Uma.

He passes this way…

together with the young woman whose soft breasts fill her taut bodice

He passes this way…

together with the woman whose smile is white as pearl

He passes this way…

together with the woman, perfectly adorned whose mound of Venus is veiled in cloth

He passes this way…

with the woman whose brow is the crescent moon.

Following are sculptures of the divine couple where Shiva passed his devotees way and so did Uma along with him:

Tamil nayanmar saint Sundarar from eighth-century with wife Paravai

Tiruvengadu / Tiruvenkadu, Tanjavur, Tamil Nadu, India

11th Century, Chola, Bronze, 91.6 cm (H)

Tanjore Art Gallery

Photo Credit: American Institute of Indian Studies – 22072

Ardhanarishvara

Ardhanarishvara – murti

Tiruvenkadu, Thanjavur District, Tamil Nadu, India

11th Century CE, Chola, Granite, 23.1 cm (H)

Government Museum, Chennai (Madras)

Published in : Krishna, Nanditha, Shakti in Art and Religion. Madras: CP Ramaswami Aiyar Institute of Indological Research.

Shiva as Ardha-nari or the half woman is celebrated as the form when Shiva takes Uma as one-half of his body. The master sculptor fuses the masculine and feminine aspects of the deity into one. The images of Ardhanarishvara can be seen in stone on temple walls as well as in portable bronze sculptures. The bronze sculpture on the left is a utsavamurti. Its pedestal has holes to tie to a palanquin which temple servants carried during processions. The stone sculpture on the right would have been a steady, immovable temple sculpture.

Ardhanarishvara

Ugrakaliamman temple, Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, India

10th Century CE, Chola, Granite, 117 cm (H)

Tanjore Art Gallery

Photo Credit: American Institute of Indian Studies – 9879

In both examples, the artist cast Uma’s side of the jawline as gently curved, and Shiva’s shows a straight profile. For the body as well, Uma’s side has rounded breast, a narrow waist with a curved hip, and Shiva has a broader chest, straight waist, and firm hip profile. A similar distinction is notable in their ornamentation and dress, from the crown and earrings to long-skirted, slender female leg to short waist cloth male thigh.

Uma with Shiva Tripurantaka

Shiva as Tripurantaka and Uma

Tamil Nadu, India

10th Century CE (950-960 CE), Chola, Bronze

Shive: 81.9 cm (H), Uma 65.1 cm (H)

Photo Credit: The Cleveland Museum of Art, John L. Severance Fund 1961.94

Shiva as Tripurantaka is accredited with destroying three mythical cities of the asuras. His manifestation, described in all the Agamic treatises, has as many as eight prescribed features for iconic representation: either standing in sambhanga to atibhanga posture (form no flexion of the body to multi-flexions) or seated sukhasana. When standing, Uma accompanies Shiva; she may be addressed as Tripurasundari, the Beauty of the Three Cities) or perhaps as Tripuravijayi (Victorix of the Three Cities).

Looking at the slenderness of the body, it seems like the artist of the Tripuravijaya murti cast both Shiva and Uma just out of their adolescence. Although cast separately, the two sculptures are placed beside each other on a single pedestal. Shiva is in a dramatic tribhanga pose. He in this image has an exceedingly slender torso with broad shoulders, powerful thighs, and neatly formed knees and ankles, creating an image of athletic perfection. In his graceful posture, we can imagine that shortly Shiva will effortlessly raise his arms and move his body dramatically to use the bow and arrow (now-missing) to kill the asuras. Supporting him, Uma is also in tribhanga pose with her bent left knee and feet slightly closer than usual. The goddess in peace looks beautiful next to her victorious consort.

Uma with Shiva Chandrashekhara

Kevala Chandrashekhar

Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, India

12th Century, Chola, Bronze, 76.2 cm (H)

Tanjore Art Gallery

Photo Credit: American Institute of Indian Studies – 7530

Chandrashekhar is a mesmerizing name of Lord Shiva formed by the union of two words – Chandra (moon) and Shekhar (crown), meaning the Lord with the moon as his crown.

When Chandrashekhar presented alone is called Kevala (alone). However, with Uma next to him, the popular sculptures of Chola bronzes is called Alinga – Chandrashekhara Murti. In the composition, as shown in the bronze, Chandrashekhar is shown embracing Uma. Both in standing positions have their head slightly turned towards each other. Uma is in her constant pose of tribhanga with her right leg firmly planted on the pedestal while her left is slightly flexed. Her one hand is raised to hold a lotus or blue lily blossom, while the other is further away from the body than usual, allowing Shiva’s hand to embrace her waist. Shiva, too, stands in a slightly flexed contrapposto with his right knee slightly bent and foot rotated towards Uma. Placed on the same visvapadma, the composition celebrates the intimacy between the divine couple.

Shiva Embracing His Consort, Uma

(Alingana – Chandrashekhara Murti)

Piravamaruntisvara temple, Tirutturaippundi, Tanjavur District, Tamil Nadu, India

1100 CE, Chola, Bronze

Shiva 38.4 cm (H), Uma 33 cm (H)

Photo Credit: Donaldson, Thomas Eugene. Síva-Pārvatī and Allied Images: Their Iconography and Body Language. 1. Vol. 2. 2 vols. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld, 2007.

Copyright: National Museum, New Delhi

Both the graceful, richly ornamented sculptures have similar jewelry and patterned drapery casted from their waist and below.

Uma as Sivakami with Shiva as Nataraja

Shiva as Nataraja and Sivakami

Nagesvarasvami temple, Kumbakonam,

Tanjavur District, Tamil Nadu, India

11th Century CE, Chola, Bronze

Shive: 155.8 cm (H), Uma 129.8 cm (H)

Photo Credit: Donaldson, Thomas Eugene. Síva-Pārvatī and Allied Images:

Their Iconography and Body Language. 1. Vol. 2. 2 vols. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld, 2007.

Copyright: French Institute of Pondicherry/ Ecole Francaise d’Extreme-Orient

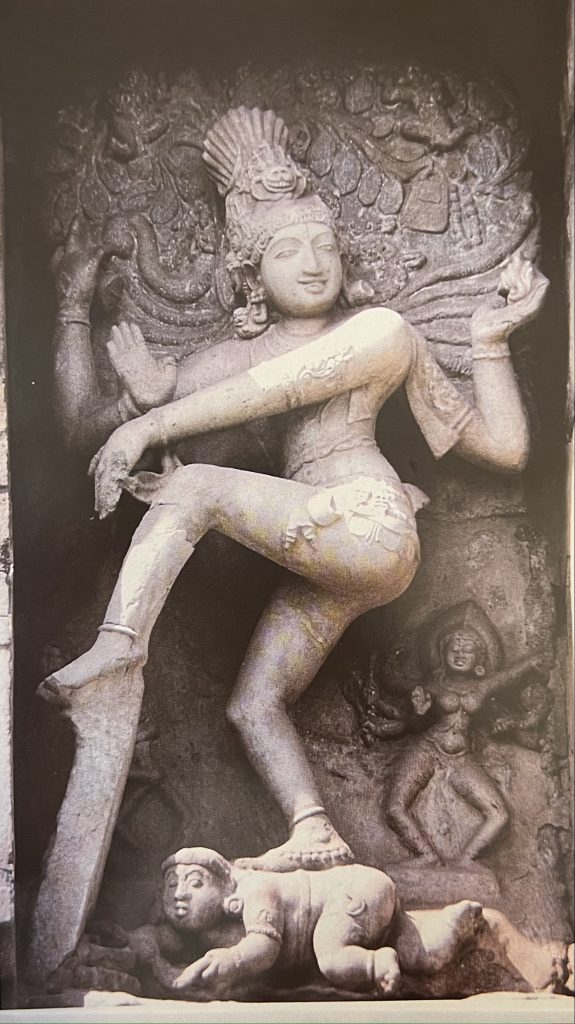

Shiva as Nataraja (Lord of Dance)— with his exquisite face, elegant torso, perfectly proportioned thighs and legs— is indeed the epitome of beauty. Identified as the supreme being, Nataraja dances triumphantly at defeating demons or for the pleasure of his consort. His performing ananda tandava, or the dance of bliss, can bring the universe into being, sustains it with his rhythm and then dances it out of existence.

Cast separately but placed together on the left of Nataraja is Sivakami, a manifestation of Uma. She is known as the beautiful woman, wife or beloved of the Nataraja. Even though unified by the composition, Sivakami is in her own prabha aureole. As we know, Nataraja’s aureole represents the cyclical, cosmic concept of time, an endless cycle of creation and destruction. What does the aureole around Sivakami represent? Does it mean that the goddess is not only taking pleasure in her husband’s dance but also representing herself as an equally powerful being? Especially with her left hand raised waist high, with her palm up appearing to hold an object rather than her usual pose of holding a flower.

Nataraja in Chola kingdom also have stories of dance off with Kali, another manifestation of Uma. Depicted in stone sculpture and murals, there are small images of Kali dancing alongside him.

Shiva as Nataraja with Kali Dancing in background

Tanjavur District, Tamil Nadu, India

11th Century CE, Chola, Bronze

Photo Credit: Donaldson, Thomas Eugene. Síva-Pārvatī and Allied Images:

Their Iconography and Body Language. 1. Vol. 2. 2 vols. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld, 2007.

An interesting story of the dance off from Tiruvalankattupuranam version summarized by Shulman is:

“She created Kali, who killed the demons but upon drinking their blood became

intoxicated and ranged through the forest near Tiruvalankadu, madly

devouring living creatures. At Närada’s request, Siva agreed to quell her

fury; he came down from Kailasa and engaged her in a dance contest. Kali

excelled at the lasya, but when he began his tândava, the worlds shook,

constellations fell to earth, and Kali tainted upon the ground. When she

revived, she shyly admitted defeat, for Siva had done the Urdhvatandava

with one leg lifted high above his head, and modesty prevented Kali from

imitating this step. Siva granted that she was the second-best dancer in the

world, but he himself continued to dance violently until the gods begged

Uma to help them calm him down in order to avert any calamity to the universe.

Finally calm, Siva said that he danced in order to give a vision to the sages in the forest.”

This story raises many questions. Is there a connection between the bronze sculpture with the stone and mural. Is the bronze of Sivakami in her own prabha aureole denoting the power she has on Shiva to calm him down? Also, even though they are one, the story differentiates Kali from Uma. The artists who make them in stone and bronze also do the same. Why? One possible way to understand this is that an audience of devotees gain pleasure in the moment of the competition but also know that there is cosmic stability. Seeing the competition gives salvation.

Uma with Shiva Vrishabhavahana

Here Shiva is Vrishabhavahana, he who has a bull for his vehicle. His face is exquisite and serene, with dreamy eyes and matted hair wrapped around his head and held in place by a snakey turban. One leg crosses casually over the other while a hand rests on his thigh, to suggest that he is leaning on Nandi, his bull, which is missing in this set. Along with him, Uma’s hip curves to the left.

These two sculptures are not joined a common pedestal and would have been processed separately as would Nandi. Shiva’s pedestal has holes to tie to a palanquin which temple servants carried. However, Uma’s base has no holes, perhaps it was attache to another larger, now missing. This is what happens to portable images; they change with use and over time.

Shiva Vrishabhavhana with Uma

Tiruvengadu/ Tiruvenkadu, Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, India

11th Century CE, Chola, Bronze, 106.7 cm (H)

Tanjore Art Gallery

Photo Credit: American Institute of Indian Studies – 10513

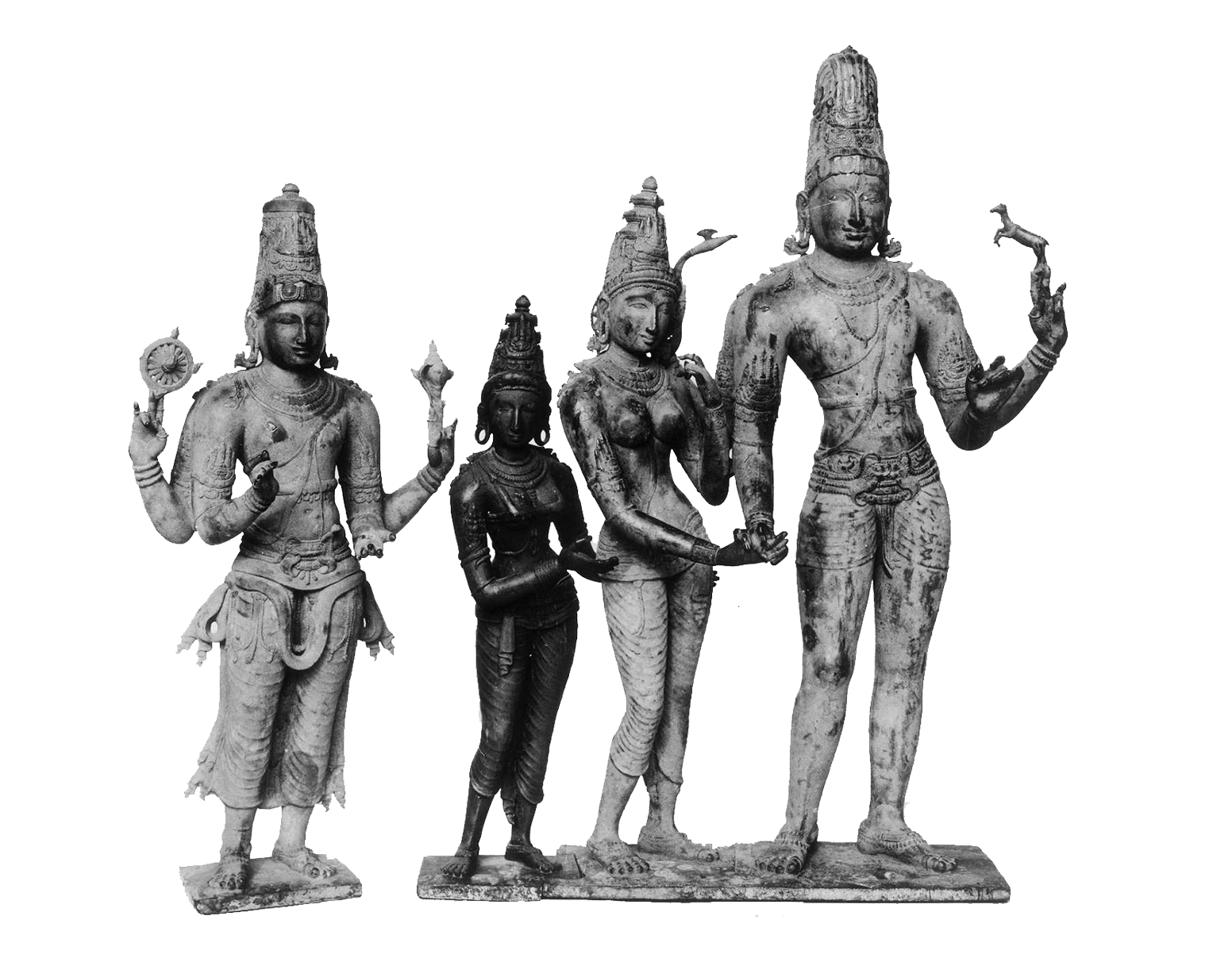

Uma as Mother

According to Shaiva Siddhantha, Shiva bestows his grace on an individual soul only in the company of Uma-Parameshwari. A bronze image of the god together with his wife, Uma and their son Skanda is thus the principal image at every single temple, wealthy or otherwise. During the Chola period, the Somaskanda murti was the main object of worship during festive rites, when the sculptures were taken out in processions. For a fact, if at any festival, a specific sculpture or composition was missing, it could be substituted by the Somaskanda murti for the ritual. It may be because of the nature of the composition where Shiva and Uma represent affectionate parents to Skanda, making the devotees feel the attachment too. The only member missing in the group is the elder son Ganesha. There is no images of the holy family that include both Ganesha and Skanda in the same composition from the Chola dynasty. Some scholars suggest the reason could be that Ganesha was created by Uma herself and was not fathered by Shiva, whereas Skanda sprang from Shiva’s semen. Furthermore, as per the Tamil mythology, there is a constant antagonism between Shiva and Ganesha, whom the goddess dearly loves.

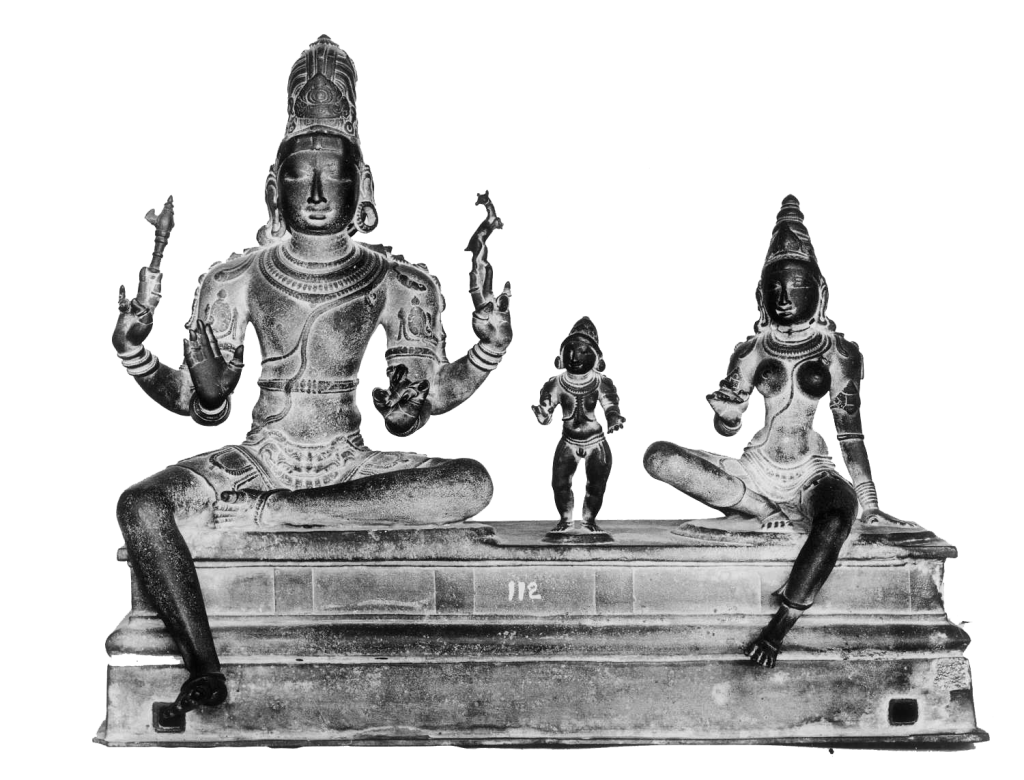

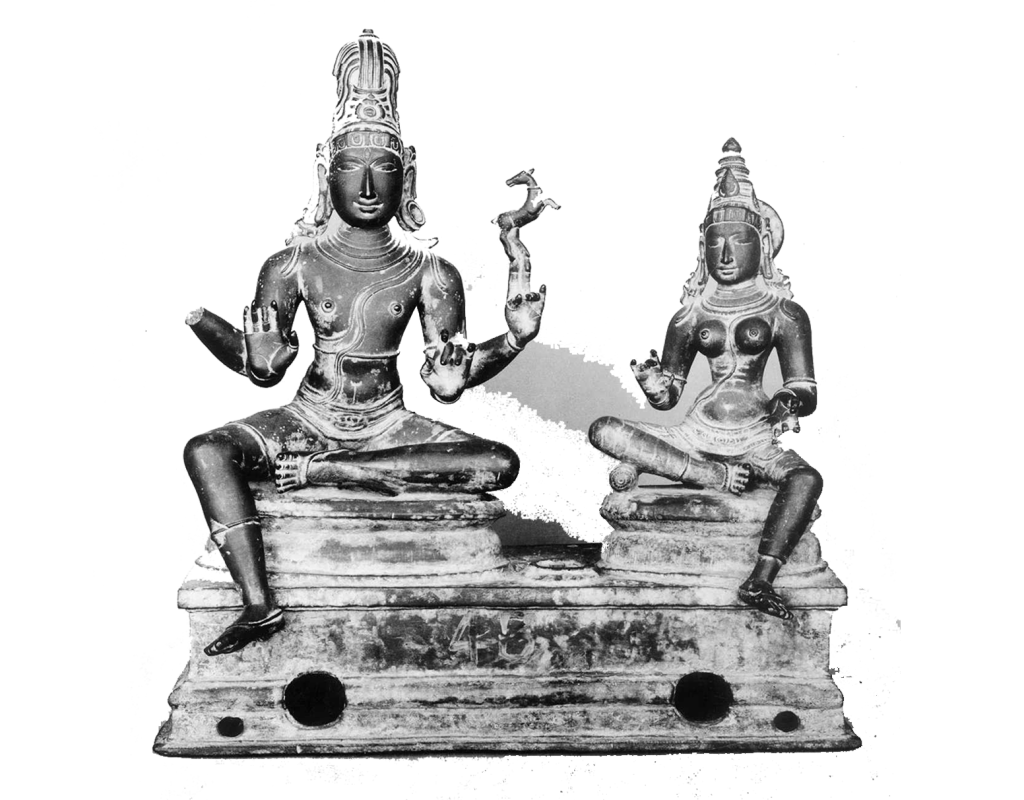

Shiva and Uma with their child Skanda (Somaskanda murti),

Pattisvaram, Tanjavur District, Tamil Nadu, India

10th Century, Chola, Bronze, 20 in (H)

Tanjore Art Gallery

Photo Credit: American Institute of Indian Studies – 10086, 10087

Somaskanda Murti with Shiva and Uma, Skanda missing

Tiruvidaimardur/ Tiruvaidaimarudur,, Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, India

11th Century, Chola, Bronze

Tanjore Art Gallery

Photo Credit: American Institute of Indian Studies – 87974

Multiple Somaskanda bronzes exist to date with Shiva and Uma in their graceful body poses with Skanda always placed on the front edge in the middle, standing, seated or dancing. Skanda is sometimes missing from compositions now. Shiva and Uma are sculpted seated in lalitasana, with one foot crossed in front and the other leg pendant. Shiva’s left leg is tucked in, whereas Uma’s right is folded. The artists uses this formatting to evenly balance the arrangement with the pendant leg on the outside or ends of the seat.

Uma from the composition, is richly adorned in a karanda-mukuta (conical coiffure or crown studded with jewels) with multiple necklaces, Brahmanical sacred thread, elaborate armletaer of bangles, and rings. Her heavy jewellery, the roundness of her breasts, with the circle incised around her nipples set her to look as the mother in this composition. Another interesting casting is the stylized curve of the upper edge of the skirt and her drape that falls down and can be noticed around Uma’s ankles.

Uma from the composition, is richly adorned in a karanda-mukuta (conical coiffure or crown studded with jewels) with multiple necklaces, Brahmanical sacred thread, elaborate armletaer of bangles, and rings. Her heavy jewellery, the roundness of her breasts, with the circle incised around her nipples set her to look as the mother in this composition. Another interesting casting is the stylized curve of the upper edge of the skirt and her drape that falls down and can be noticed around Uma’s ankles.

Uma from Somaskanda murti,

Pattisvaram, Tanjavur District, Tamil Nadu, India

10th Century, Chola, Bronze

Tanjore Art Gallery

Photo Credit: American Institute of Indian Studies – 10086, 10087

Durga

While Uma-Parvati is the name given to goddess in her role as wife to Shiva, as her own powerful self, the devi is addressed as Durga, the Impassable One.

The powerful goddess, the destroyer of demonic forces that threaten the universe, is famously known for killing the buffalo demon. She is not only found in the context of a Shiva temple but also is homed in the Vaishnava context as Vishu’s sister. From the Chola period, there are multiple figures of Durga in stone and bronze visually depicting herself and her battle through different postures and gestures. These different illustrated iconographies of Durga clarify the context in which she was worshipped.

The image from the eleventh century, now located at the Brooklyn Museum in New York, presents an exquisite image of Durga. The beautiful bodied sculpture is elaborately adorned in bronze. It is represented with four hands, the upper two carrying the usual attributes of Vishnu – discus (chakra) and conch shell (shankha), and the lower right hand in abhaya pose, while the left rests gracefully against her thigh in a gesture of ease (katyavalambita). With Vishnu iconographies, this particular sculpture supports her popular name as Vishnu-Durgai, worshipped in a Vaishnava temple.

The sculptor presents a lithe, youthful goddess whose form is almost adolescent. On a lotus base placed on a rectangular pedestal with vertical tangs to support a prabha (aureole), Durga stands in an upright position. Cast resting her weight equally on both feet in samabhanga pose (figure in equipoise), in contrast to Uma’s tribhanga (triple bend) posture.

Her body is richly ornamented with similar jewelry to Uma, however with a significantly shorter lower garment, which is patterned instead of pleated and have extra fabric knotted with bowlike ties falling down from both sides of her waist held in place with a jeweled girdle.

Durga holding Vishnu attributes:

Durga,

Tamil Nadu, India

Ca. 970, Chola, Bronze, 57.2 X 20 X 16.8cm, 11. 34kg

Photo Credit: The Brooklyn Museum,

Gift of Georgia and Michael de Havenon, 1992.142. Creative Commons-BY (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 1992.142_SL1.jpg)

Maheshwari

Maheshwari,

Velankanni, Thanjavur District, Tamil Nadu, India

10th Century, Chola, Bronze,

Photo Credit: The Madras Government Museum

Published in : Krishna, Nanditha, Shakti in Art and Religion. Madras: CP Ramaswami Aiyar Institute of Indological Research.

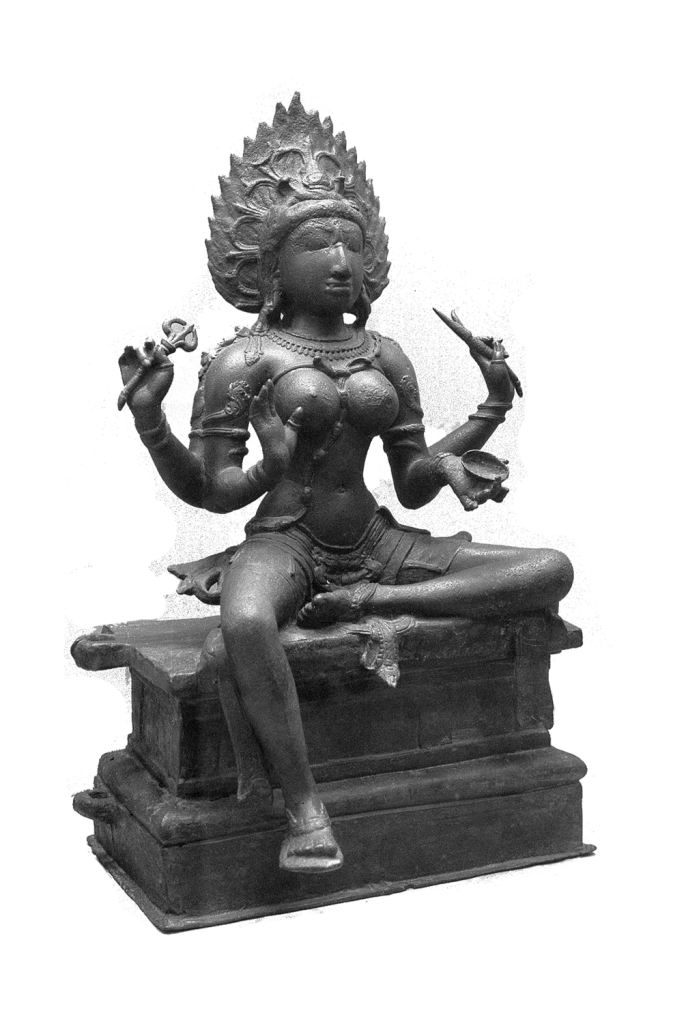

As the consort of Maheshwara, Uma, in her manifestation as Maeshwari, is depicted sitting in Shiva’s royal position or lalitasana. The figure sits on a throne with the left leg tucked inwards on the seat and the other hanging down to rest on the support. Furthermore, like Shiva, the sculptor depicts the goddess carrying the axe and an antelope in the upper hand. This is the only image in the Madras Government Museum representing this iconography and theme. Another notable detail of the sculpture is the hair which resembles the flame as the same in Kali bronzes.

Maheshwari holding Shiva attributes:

Mahishasuramardini/ Nishumbasudani

Yet another manifestation is Mahishaduramardini. In this role, the goddess is represented killing the demon king Mahishasura (demon with a buffalo head), who is always seen lying in her feet.

The bronze image, is however of Nishumbasudani. The animated bronze figure shows the devi sitting with one leg bent to rest upon her seat while her other foot is placed upon the figure of demon Nishumbha. Her left hand in kataka-mudra depicting the trident, while her other hands hold the cobra, sword, shield, bow, bell, dagger and skull cup.

Nishumbasudani

Turaikkadu, Thanjavur District, Tamil Nadu, India

10th Century, Bronze, 75 cm (H)

Government Museum, Chennai (Madras),

Photo Credit: American Institute of Indian Studies, 81242

Kali/ Bhadrakali

In her cosmic energy, the goddess remains a powerful force in south India. The warrior goddess, destroyer of demons’ more peaceful representation in sculptures can be seen:

Kali

Senniyanvidudi, Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, India

10th Century, Chola, Bronze, 44 cm (H)

Government Museum, Chennai (Madras)

Photo Credit: American Institute of Indian Studies – 81226

Kali

Kali, the powerful goddess is also referred as Kala pidari in Rajaraja’s Tanjavur inscription. Seated in the posture lalitasana or royal ease. Her two rear hands hold the trident and the noose, both weapons with which Kali redeems sinners by destroying their evil deeds.

Although the form contains several fierce allusions, this particular sculpture shows her serene face framed by matted hair that rises like a halo behind her head. Her breastplate shows intertwined serpentines and her sacred cord is threaded with human skulls.

Bhadrakali

In contrast, some scholars suggest when represented with more than two pairs of arms, the auspicious Kali is known as Bhadrakali.

The sculptor in the standing image has modelled the goddess as the tranquil protector with a smiling face. She is holding weapons in the back, whereas one of the front two arms is raised in a gesture of protection and the other lowered in a wish-granting gesture reassures their worshippers of her grace. Could be imagined as Bhadrakali’s own crown, her hair is arranged in a flaming halo adorned with a serpentine and have Shiva’s crescent moon.

Bhadrakali,

Thanjavur District, Tamil Nadu, India

1100-1199 CE, Bronze, 68.6 cm (H)

Tanjore Art Gallery, No.109,

Photo Credit: American Institute of Indian Studies, 7827

This exhibition is an effort to collect images of Uma-Parmeshwari from Thanjavur district’s 10th and 11th centuries in one place. This can be a much larger project to curate images of the Devi from throughout the Chola empire. The same can inspire more such websites of several deities and particularly goddesses from the period to understand and explore their iconography. Furthermore, this resource is a starting point and can be used to examine the Shakti iconography with a focus on ornament, gait, and posture.

The work during these two months inspired me to further explore the topic and continue working on the subject. For a much larger project, one can explore the ornamentation and clothing as cast on and how they further adorn the bronze sculpture. Inscriptions from the period with detailed information about the jewellery still exist. However, the actual jewellery is missing or anticipated to be re-used for different designs over the eras. Even though Chola jewellery has not survived, this exhibition can lead to a project to understand jewellery and temple jewellery as a whole. It can also lead to understanding if there were different ornamentation and rituals for dressing different deities during the Chola empire.

Curator:

My name is Saloni Mahajan, and I am a doctoral student in the Performance Studies program at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. Currently, I am studying the costumes, composition, and history of Indian performances, primarily focusing on alankara (ornament and clothes) and shringara (adornment).

Other than this, I am also an international costume designer, fashion stylist and graphic designer. My experiences include working in Bollywood and the entertainment industry in Los Angeles.

You can find more about my work and background on my websites: www.salmahajan.com and www.salmahajan.work

Curating Changing Iconography, Changing Identity, was my first experience of entering in the world of art and art history. I look forward to taking this experience forward and building on this project.