This exhibition commemorates the generous gift of Dr. Carol Radcliffe Bolon’s photographic documentation of the goddess Lajja Gauri to the American Institute of Indian Studies (AIIS). Dr. Bolon’s documentation sheds light on the identity, the distinct iconographic forms, and functions of the goddess Lajja Gauri. The collection is unique as it is not only the most comprehensive study on the topic but also asserts the importance of a goddess in a widespread cult whose imagery culminated in the eleventh century and is seldom referred to in texts. The images were first published in Dr. Bolon’s book Forms of the Goddess Lajja in Indian Art. The collection along with Dr. Bolon’s commentary is valuable to understand the development of the goddess’s iconography and worship tradition.

Dr. Bolon is a scholar of Indian art and former Curator of South Asian Art, Freer and Sackler Galleries, Smithsonian Institution. She has been a senior fellow of AIIS. The exhibition is curated by Stuti Gandhi, Research Associate at Center for Art and Archaeology, AIIS.

Who is Lajja Gauri?

Lajja Gauri is the name most widely used in modern India for the image of an Indian Goddess that has a female torso and a lotus flower in place of a head, and her legs are bent up at the knees and drawn up to each side in a pose that has been described as one of “giving birth” or the uttanapad pose. The implications of this pose are important to understand the deeper meaning of the goddess’s images. In the nineteenth century, when the British archaeologists were confronted with the life-size nude squatting figure, they designated her to be ‘indecent’ and ‘shameless’. This is, however, ill-considered since the birth giving pose is used as a metaphor for creation in Indian art. In fact, Lajja Gauri can be more appropriately translated to ‘Gauri, goddess of modesty’.

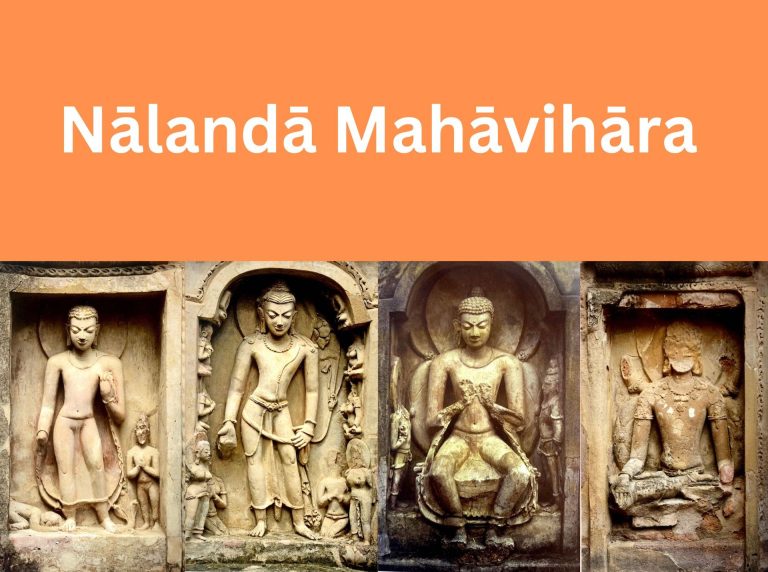

Lajja Gauri's imagery

Carol Bolon’s cross regional study reveals that Lajja Gauri figures conform to four broad iconographic configurations. The four forms of Lajja Gauri show a broad progression through time and region, growing from the minimal to nearly an iconic, and finally to the fully human.

Form I: Uttanapad Pot

The most elemental and symbolically potent Lajja Gauri representation is the birth giving (uttanapad) pot goddess. This imagery is characterised by human legs in uttanapad pose with a shape above the legs that resembles both a pot and a female’s lower torso. The figure has no upper torso and there are no breasts, arms, or head. The pot torso resembles a brimming vase, or purna kumbha.

These images of small and made of terracotta or stone. The size ranges from 2 inches square to widths or heights of 5 to 6 inches on a side. This form was popular in southern India and made in the third and fourth century but not thereafter.

Lajja Gauri

Ramligappa Lamture Government Museum, Ter, Maharasthra

Ter, Osmanabad, Maharashtra, India, 100-399 CE, Terracotta

Photo Credit: Regents of the University of Michigan, Department of the History of Art, Visual Resources Collections, ACSAA_11273

In these Form I or uttanapad pot goddess form of Lajja Gauri, the legs are joined to a truncated torso. The figure is a metaphor for a vase brimming with lotus flowers symbolic of fortune, life, and procreative power.

Form II: Lotus-headed without arms

These are like those of uttanapad pot Form I except that the torso extends up to the shoulders and includes breasts. There are no arms or head in images in this group, but the lotus is elevated to sit atop the shoulders. Almost all images are in stone and small, measuring either about 2 inches or about 5 inches on one side. This is the predominant Maharashtrian-type figure especially in the central area and was made from the fourth to the tenth century.

Lajja Gauri

Kanoria Collection, Patna

Site Unknown, Uttar Pradesh, India, 301-500 CE, Terracotta, 10.16 cm (D)

Gift of Carol R Bolon, CRB00011

The uttanapad legs in this Form II are on a torso that is more human in form than pot-like. The abdominal area has a carefully indicated navel, breasts, often a necklace, and a lotus in the place of a head. The lotus rosettes are placed to the sides of the shoulders joined to the figure.

Form III: Lotus-Headed with Arms

The Form III figures are lotus headed but with anthropomorphic female bodies with breasts and two upraised arms on the full torso with each hand holding a lotus bud, and legs in the uttanapad pose. The lotus buds in hand express pure generation. This type was made from the fourth to the tenth century. They were made in Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat as early as the fourth century and were made with great refinement of details during the Early Chalukya period in the late seventh century in Andhra and Karnataka; they continued to be made in the south until at least the ninth century. The Form III images are either small, about 2.5 or 5.5 inches, or are life size.

Lajja Gauri

Alampur Museum, Telangana

Sangameswara temple, Kunrnool, Andhra Pradesh, India, 675-699 CE CE, 35 x 41 in

Photo credit: Regents of the University of Michigan, Department of the History of Art, Visual Resources Collections, ACSAA_05638

Lajja Gauri

Badami Museum

Naganath Temple, Naganathakolla, Bagalkot, Karnataka, India, Late 601-700 CE, Sandstone, 96.52 x 71.12 cm

AIIS 30619

Form IV: Anthropomorphic

This anthropomorphic form of Lajja Gauri is a figure with a human head, full natural female torso, with raised arms, each hand holding a lotus bud as in Form III, and with legs in the birth giving pose. This is a northern type only and was never made in the south.

Lajja Gauri

Government Museum, Mathura

Site Unknown, Central India, India, 701-800 CE, Stone , 27.94 x 13.97 cm

Gift of Carol R Bolon, CRB00043

This is a monolithic platform and on the southwestern face of the solid platform, is carved an anthropomorphic Lajja Gauri. Lajja Gauri in the center of the panel is damaged. The two flanking female attendants who bear fly whisks are carved into the rock between relief pilasters. Since the bull on the Nandi mandapa platform faces the Sivalinga of rock-cut temple 21, the goddess is clearly associated with Shiva and Nandi.

The other three sides of the Nandi platform are damaged, but each panel seems to have had a ganas carved. On the panel adjacent to the goddess moving toward the right (east) a gana was seated with a pot. These ganas are commonly associated with Siva.

Symbols decoded

All the four forms of Lajja Gauri illustrate that the artists creating images of the goddess drew on various ancient symbols of fortune and fertility to communicate her power through their rich heritage of meanings. They used these symbols in combinations crouched within the female form in a birth like position. The three paramount symbols are:

Lotus

In Indian art the lotus is the symbol par excellence of fortune, fertility, and reproduction. The lotus is seen as a plant carrying the potential for future generations and is given meanings of cyclic renewal of life, of regeneration of life, or reincarnations.

Brimming pot

Like the lotus, the pot symbolizes well-being, fertility, and the power of water as the source of life. The pot also suggests the womb (yoni). The extension of the torso to include breasts, flanking buds, and a full flowering lotus in the location of the head may have taken inspiration from a purna kumbha association.

Srivasta

Srivatsa is a mark or sign of fortune; in art, it is represented with a whorl of hair, a triangle, or a cruciform flower and in its early form srivatsa has four upwardly curved “limbs.” Carol Bolon compares the combined designs of lotuses and srivastas at Bhahrut and Sanchi with the silhouette of Lajja Gauri. There is also a relationship in the meaning of Lajja Gauri and srivasta, and thereby kinship with Sri, Sri Lakshmi, and Gaja Lakshmi-all goddesses of well-being.

-

-

Purnaghata, Stupa Relief of Amaravati, Guntur, Andhra Pradesh

Government Museum at Egmore, Chennai

ca 199-100 BCE, Limestone

Photo Credit: Regents of the University of Michigan, Department of the History of Art, Visual Resources Collections, ACSAA_12151

-

-

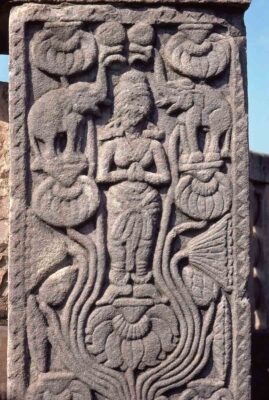

Gajalakshmi on a full-blown lotus, railing of Stupa 2

Sanchi, Madhya Pradesh, India

ca 199-100 BCE, Sandstone

Photo Credit: Regents of the University of Michigan, Department of the History of Art, Visual Resources Collections, ACSAA_03072

-

-

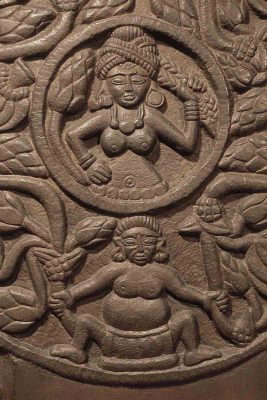

Medallion, Stupa Railing of Bharhut, Satna, Madhya Pradesh

Indian Museum, Kolkata

ca 100 BCE, Sandstone

Photo Credit: Regents of the University of Michigan, Department of the History of Art, Visual Resources Collections, ACSAA_12869

Lajja Gauri's transition into a Hindu goddess

The iconographic form of Lajja Gauri does not have any known textual or epigraphic documentation. The form of the goddess most widely known today as Lajja Gauri fits the Vedic descriptions of the mother of the gods, Aditi. There are also many traditional explanations to explain the source of the goddess. For instance, she is locally recognised as Yellamma or Renuka in Karnataka, Maharashtra, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. The visual depiction of Yellamma having outspread legs, has strong parallels with Lajja-Gauri. The rituals at associated with the Yellamma temple near Badami are associated with fertility. Some other the descriptive names are probably local inventions of no great antiquity while other names are based on rural mother goddesses.

Lajja Gauri may have originated on either a tribal or local village level as a gramadevi with a pot serving as her original aniconic form. Her fully anthropomorphized form (IV), formulated by about 500 CE as in the Elephanta, and found in situ at Ellora 21 by about 550 CE and persisting throughout Gujarat in the sixth and seventh centuries indicates her Brahminization process. As Lajja Gauri became Hinduized and admitted into the Hindu temple, she also became Hinduized mythologically in that she became considered as (assimilated to be) a consort of Shiva. She was represented with Siva’s bull and linga, and was given her own vahana, the lion of sakti. In Andhra she was represented as equal in status to the great Hindu gods in several plaques depicting groups of deities.

The change in form of this goddess from a personified symbol to a fully female form with a human head through a period of at least four centuries was probably brought about by royal patronage of the deity.

Popularization of Lajja Gauri

Fertility Function

An inscribed marble image of Lajja Gauri was discovered in 1940 on the north slope of Nagarjunakonda hill in the remains of the pillared hall of a Hindu temple. The one-line Prakrit inscription on the lower rim of the stone is written in Brahmi and reads: “Success! [This image is] caused to be made by Queen Mahadevi Khamduvula, whose husband and children are alive and who is the wife of Maharaja Siri Ehuvala Chamtamula.”

While the inscription does not give the name of the goddess, it suggests that this woman’s fortune in having her husband and children living is due to her worship of this goddess and, by extension and because the figure was probably placed within a temple shrine, that by worshiping this image other women may achieve the same auspicious state. This, we know, is the motivation for worship of such images in India today.

Political Function

The goddess Lajja Gauri was especially important to the people ruled by the Early Chalukya kings during the last two decades of the seventh century as is apparent from the number, size, and quality of her images made at this time. There are some Chalukya images that are still worshiped at sites where temples of the period stand. These temples provide an important context in which to study the role of Lajja Gauri.

Two Chalukya-period temples, the Lakulisa temple at Siddhanakolla (Bagalkot, Karnataka) and the Bala Brahma temple at Alampur (Telangana), still in worship, retain images of the goddess. They are visited by childless women or couples seeking the blessing of fertility. They are worshiped by circumambulation and application of ghee to the pudendum. Moreover, miniature dolmen like “houses” to be filled with children are also built by women or couples making pilgrimage to the site.

-

-

Lajja Gauri carved on path to the Lakulisa temple at Siddhanakolla, Bagalkot, Karnataka, India

Late 601-700 CE

AIIS 41877

-

-

Lajja Gauri carved in relief from the rock floor of a natural grotto at the Lakulisa temple at Siddhanakolla, Bagalkot, Karnataka India

Late 601-700 CE, Stone 81.28 x 99.06 cm

AIIS, 41984

The image’s significance during the mid seventh century may be the Chalukya kings’ strategy for gaining the loyalty of his diverse subjects.

Lajja Gauri

Kedaresvara temple, Belligamve, Shimoga Karnataka, India

701-800 CE, Stone, 71.12 x 38.10 cm

Gift of Carol R Bolon, CRB00036

All of the Chalukya-period examples are large, three to four feet, and are carved in relief in stone. The large size, the choice of stone for Lajja Gauri images, and the care taken in carving them indicate their considerable importance at this time. Furthermore, a sub-shrine was specially built to enshrine Lajja Gauri in front of some seventh-century temples dedicated to Shiva.

An eighth-century Lajja Gauri by the side of the Kedaresvara temple bears an inscription that records that Early Chalukya King Vinayaditya (reign 681-96 CE) imposed a tax on sonless couples. Perhaps Vinayaditya needed soldiers for his military campaigns and the images of the fertility goddess were housed at special temples to serve as recourse for sonless women.

Agrarian Prosperity

Several Lajja Gauri images are found on walls of tanks. There are two such examples from Gujarat and another from Aihole in Karnataka. The Ramesvara Temple at Ellora is also situated near a waterfall. Large Lajja Gauri images that are still in worship are near a tank, river, pond, or in a stepwell. In two images from Ramatola (below), the figure placed on the right side of a wide rectangular stone plaque which includes two miniature tanks (kundas) on the left side. In the larger of the two plaques there is a third tank below the goddess.

Each tank has a hole cut through its side wall nearest the figure. Water poured into the tank runs out the hole onto the goddess. This resembles a tank near the goddess in a standard in a temple setting, for bathing. Association with water may indicate that she was also worshipped for agrarian prosperity.

-

-

Lajja Gauri

Nagpur Central Museum Ramatola, Bhandara, Maharashtra, India

301-600 CE, Stone, 15.24 x 22.23 cm

Gift of Carol R Bolon, CRB00016

-

-

Lajja Gauri

Nagpur Central Museum Ramatola, Bhandara, Maharashtra, India

301-600 CE, Stone, 15.24 x 22.23 cm

Gift of Carol R Bolon, CRB00017

Lajja Gauri in Kashmir Smast

The Kashmir Smast caves, also called Kashmir Smats, are a series of natural limestone caves, artificially expanded from the Kushan to the Shahi periods, situated in the Babuzai Sakrah mountains in the Katlang Valley Mardan in Northern Pakistan. Seals showing either Lajja Gauri figures or other related symbols or inscriptions have been recorded from this site. This has historical value since the seals are unique in character but also because they are distinct from the cultural and religious aspects of the people during the time of Buddhism. These seals here came through illegal digging and are without any proper archaeological context.

Recent discoveries of the Lajja Gauri image

An image of ‘Lajja Gauri’ carved on a huge boulder has been discovered at Cherial village in Telangana, one of the petroglyphs that have been discovered in and around the Ratnagiri and Rajapur districts also depicts the goddess and a Lajja Gauri idol was found on the road in Udupi, Karnataka.

Acknowledgement

We wish to thank Dr. Carol Bolon under whose guidance Stuti Gandhi, Research Associate at Center for Art and Archaeology, AIIS curated this exhibition. We also want to acknowledge the American Council for Southern Asian Art (ACSAA), M. Nasim Khan, Adjunct Professor, Hazara University, Pakistan and Stella Dupuis whose images, publications and video respectively have been used to develop this exhibition