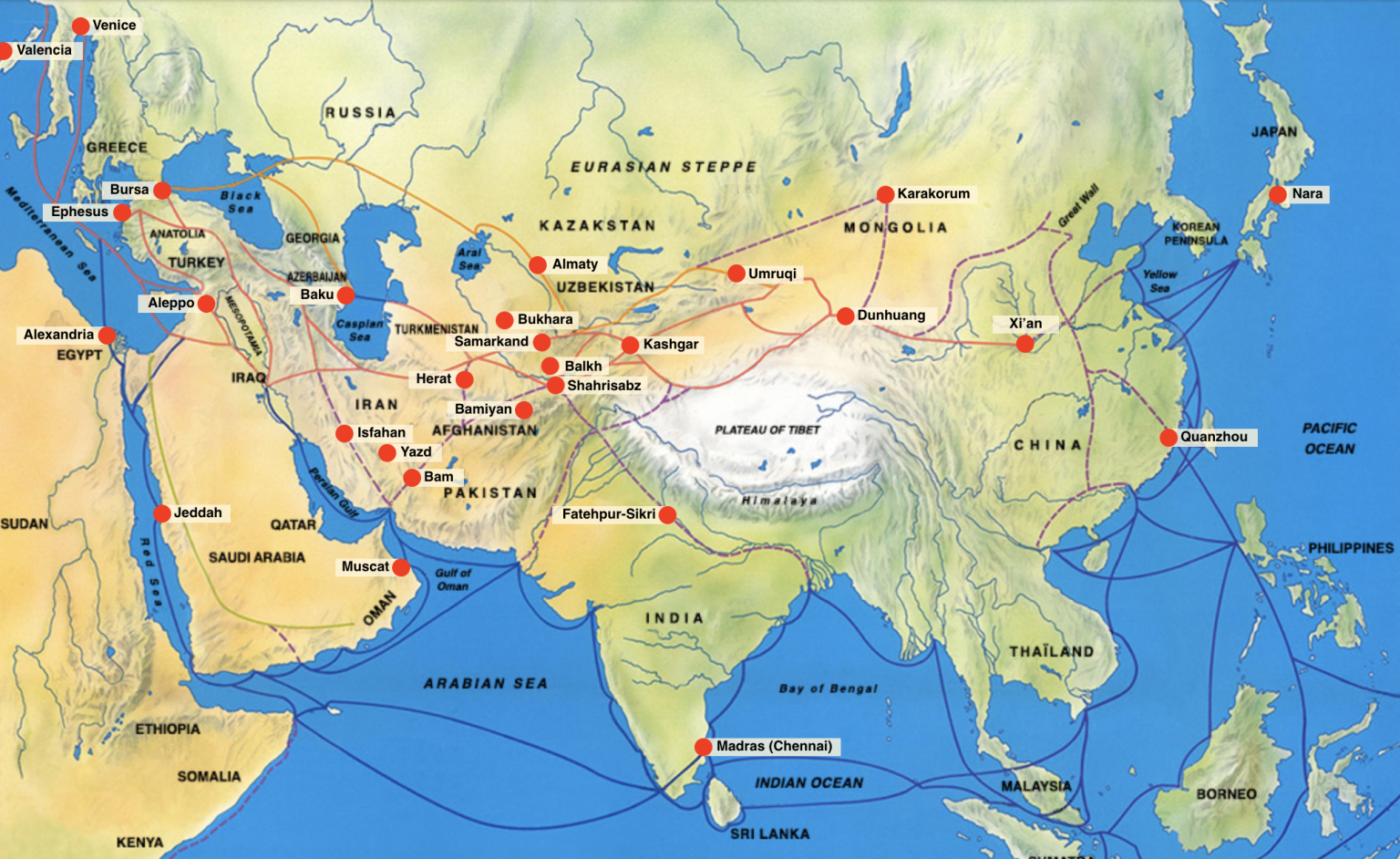

The discoveries of numerous hoards bearing foreign iconography in India’s Maharashtra state over the last century have sparked a line of queries into this central coastal region, particularly regarding its connections to the Silk Route. Also referred to as the Silk Road, the Silk Route is a term encompassing the vast and frequently shifting land and maritime trade networks that facilitated the movement and exchange of goods, cultural traditions, and people across the Asian, African, and European continents.

The archaeological discoveries from the Ancient Maharashtrian cities of Ter, Paithan, and Brahmapuri reveal the function of these sites as epicenters of production, trade, and cultural exchange during the height of the Roman Empire between the 3rd century BCE and 3rd century CE. There was frequent contact between these two societies, with trade functioning as a primary intermediary.

This exhibition consists of four sections focusing on Female Figurines, Zoomorphism, Molds, and Amulets and Medallions. Each section presents the assemblages from Maharashtra with contemporaneous examples from across the ancient world as a means for demonstrating the extensive network of cultural exchange that was taking place.

The bronze Poseidon statuette unearthed from Brahmapuri illustrates the contact between the Ancient Mediterranean world and Maharashtra. Notably, while this artifact may have been produced under Roman rule in the Mediterranean, Poseidon actually belongs to the Greek pantheon of deities. As such, the production of this bronze Poseidon indicates that despite being under the jurisdiction of the Roman Empire, the Greeks not only retained their religious and artistic traditions, but continued to disseminate them across the ancient world. Indeed, the retention of local artistic traditions can also be observed in Gaul, Dacia, and Ptolemaic Egypt following annexation into the Roman Empire.

This exhibit focuses on the flow of aesthetics and artistic techniques in the ancient world, with a focus on Romanization, which describes the influence of foreign cultural typesites on imperial Roman culture and vice-versa. Emphasis is placed on the retention of local artistic traditions in Roman colonies, a concept referred to as creolization, deriving from the term for the combining of two languages to create a new composite language.

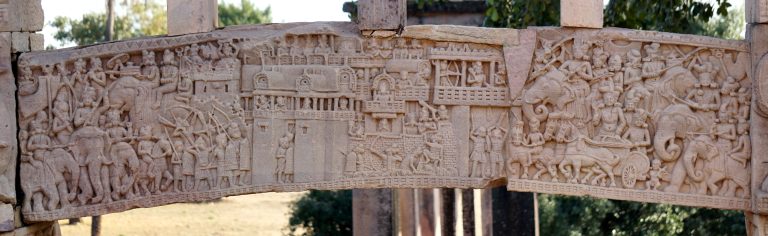

Two modest temples referred to as the North Temple and South Temple were discovered at Paithan. Construction on the North Temple began in approximately the 5th century BCE, while the South Temple began construction no later than the 7th century BCE. Although these structures likely held only local significance, they demonstrate a creolization of Maharashtrian and the Roman architectural styles and building techniques. In particular, the plinths exhibit visual similarities with column bases originating from the Roman world, and can even be found among contemporaneous temples in Maharashtra such as the Rāmtēk Temple complex. Meanwhile, the foundations of the North and South Temples adhere to traditional Indian architectural principles.

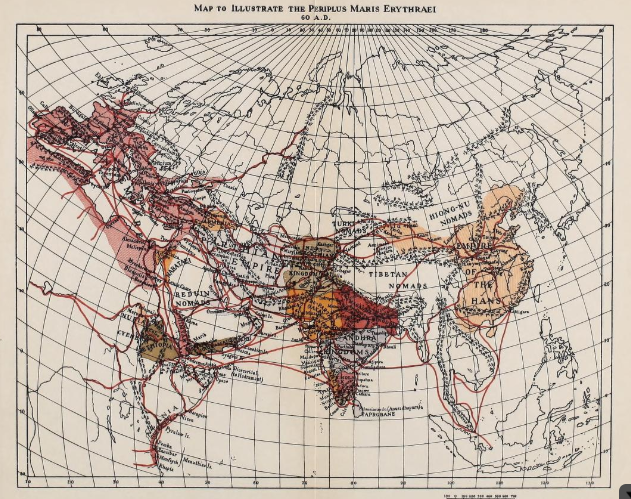

Composed in the first century by a Greco-Roman author, the Periplus Maris Erythraei was created as a guide for merchants who engaged in the maritime trade of the Silk Route. The Periplus contained information pertaining to the sea trading routes, ports, merchandise, and even references specific goods and centers of trade including the ancient cities of Tagara (Ter) and Paithan. Another site that received considerable attention in the Periplus was the port city of Alexandria in Ptolemaic Egypt, which at the time of its authorship was under Roman imperial rule. One such example of this ancient seafaring trade can be found on the island of Socotra, which sits near the entrance of the Red Sea that lead to the port at Alexandria. A number of Brahmi inscriptions and images of Satavahana-style ships were found inscribed in the caves of this island, leading scholars to suspect the use of this island as an intermediary point between the ports of India and Alexandria for seafaring merchants.

A similar framework referred to as transculturalism recognizes Silk Route trade as having been overwhelmingly facilitated by the contact between individuals from myriad sociocultural backgrounds. More and more, the ‘human’ side of the Silk Route continues to come to light, revealing the intimate and personal side of this inter-continental exchange network. This exhibition presents artifacts from Ter, Paithan, and Brahmapuri that have been selected based on their embodiment of transculturalism and artistic creolization. By way of highlighting the local and foreign aesthetics and techniques associated with each object, the cosmopolitanism of these ancient cities, and the agency of the artists and merchants that interacted within them, may be discerned.

Female Figurines

Fertility Figurine, House 1.8.5, Via Dell’Abbondanza, Pompeii, Roman Empire, 1st Century BCE-1st Century CE, Ivory.

.

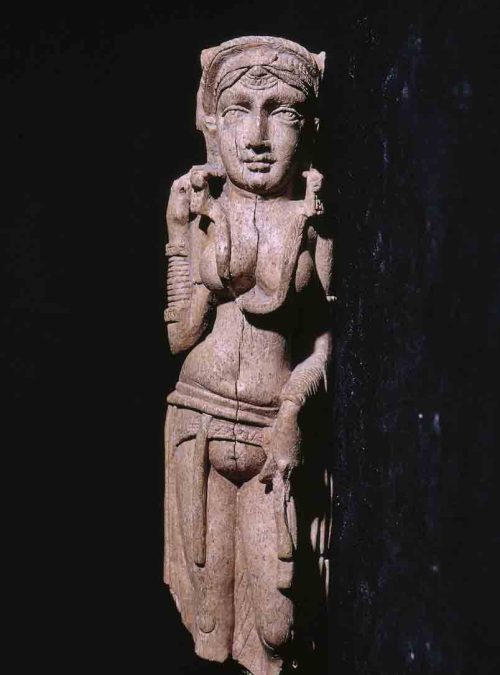

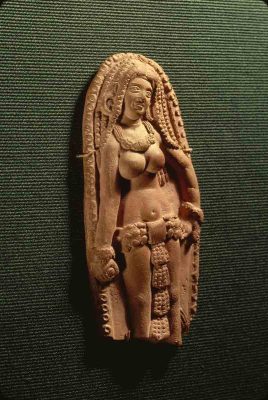

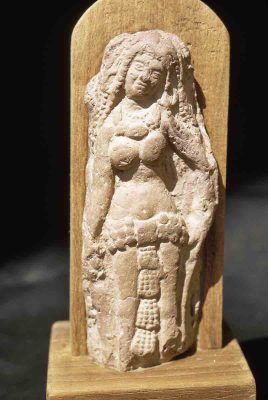

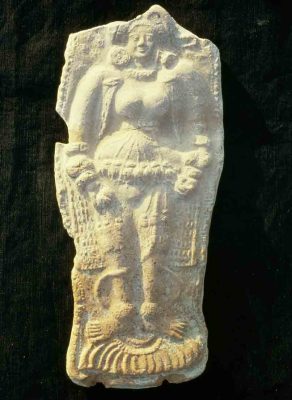

Among the most prolific forms found in the art of ancient Eurasia are the so-called ‘mother goddess’ and ‘fertility’ female figurines. These terms, however, tend to reduce the identity and function of these figures to their reproductive and maternal roles. In actuality, many questions remain concerning how these figurines may have been perceived at their time of production and use. The ubiquitous representation of these female figurines may suggest a degree of typecasting in the context of a patriarchal society, and as such, raises questions about the role of women in these environments. The popularity of these female figurines in the Indian Subcontinent, Mediterranean, and the Near East not only points to the cultural and economic significance of these objects, but also reveals one such avenue through which aesthetics and traditions were disseminated in the ancient world. At Ter and Paithan, several of these ‘mother goddess’ types were unearthed.

In the context of these two sites, the figurines may be divided into two categories consisting of depictions of the goddess Lajja Gauri, and depictions of other female deities that are either unidentifiable or exhibit a conglomeration of iconographic traits. Both types of female figurines found at Ter and Paithan are comparable to figurines found throughout the Roman Empire, including Ptolemaic Egypt, the Italian Peninsula, and Gandhara. It is suggested that Maharashtra was one such venue for the production and exportation of these figurines.

The presence of comparable figurines from Ter and Paithan suggest a Maharashtrian origin for the Pompeii ‘Fertility Figurine’. In particular, the presence of female figurines that feature a nearly identical facial physiognomy, remarkably similar adornments, and the same flanking attendants situate Maharashtra as a potential site for the production of this infamous piece. Maharashtra’s coastal proximity also addresses the maritime trade alluded to in the wall mural at House 1.8.5 where the ivory figurine was found.

Excavated from the courtyard of House I.8.5 along the Via dell’Abbondanza in Pompeii, this ivory figurine features a voluptuous figure with exaggerated feminine features. The figurine is decorated in jewelry and features a voluminous hairstyle adorned with an elaborate headdress. A plethora of bracelets and anklets cover the arms and legs, and a decorative waist belt is fastened around the hips. The rest of the body is left bare. Notably, House I.8.5 also included a graffito depicting a ship located on the West wall of a room located off the atrium where the statuette was found. This ship graffito, as well as the exotic figurine, has led scholars to believe that this house was owned by a successful merchant.

The female figurines from Ter and Paithan exhibit characteristics derived from the artistic traditions rooted in the Indian Subcontinent and abroad. These figurines display a number of differences and similarities in terms of their iconography, medium, and supposed functions. A conglomeration of local and foreign conventions can be observed in the figurines from Ter and Paithan. As such, these figurines may be interpreted as the physical embodiment of cosmopolitanism in ancient Maharashtra. The presence of analogous figurines found across the Roman Empire at sites such as Bagram, Afghanistan and in other areas of the Indian subcontinent such as Mathura, provides a glimpse into the dissemination of these figurines across time and space.

These ivory figurines discovered in Bagram, Afghanistan, feature a number of similarities to the terracotta figurines found at Ter. The tribhanga pose, exaggerated feminine proportions, prominent breasts, and sumptuous jewelry are rooted in Indian aesthetics. The ivory plaque featuring the women and children was likely positioned above the entrance to a women’s quarters. The ivory statuette may have served as a handle or a trading token. The sea-creature that the woman stands on, known as a makara, is another indicator of maritime trade.

The female body in Indian art carries connotations associated with fertility and renewal. Nudity in the context of these female deities is considered to be analogous with purity and, in the case of Lajja Gauri, modesty. Indeed, while the presentation of these nude and semi-nude deities certainly alludes to the erotic, it is also a marker of the being’s divine status, and of her life-giving capabilities. In addition to the prominent breasts and genitalia, these female deities may also be depicted in a tribhanga pose, which finds its origins in the Indian Subcontinent. tribhanga describes a woman leaning such that ‘three curves’ to the body are created, giving her an exaggerated feminine shape. This pose is symbolic of fertility.

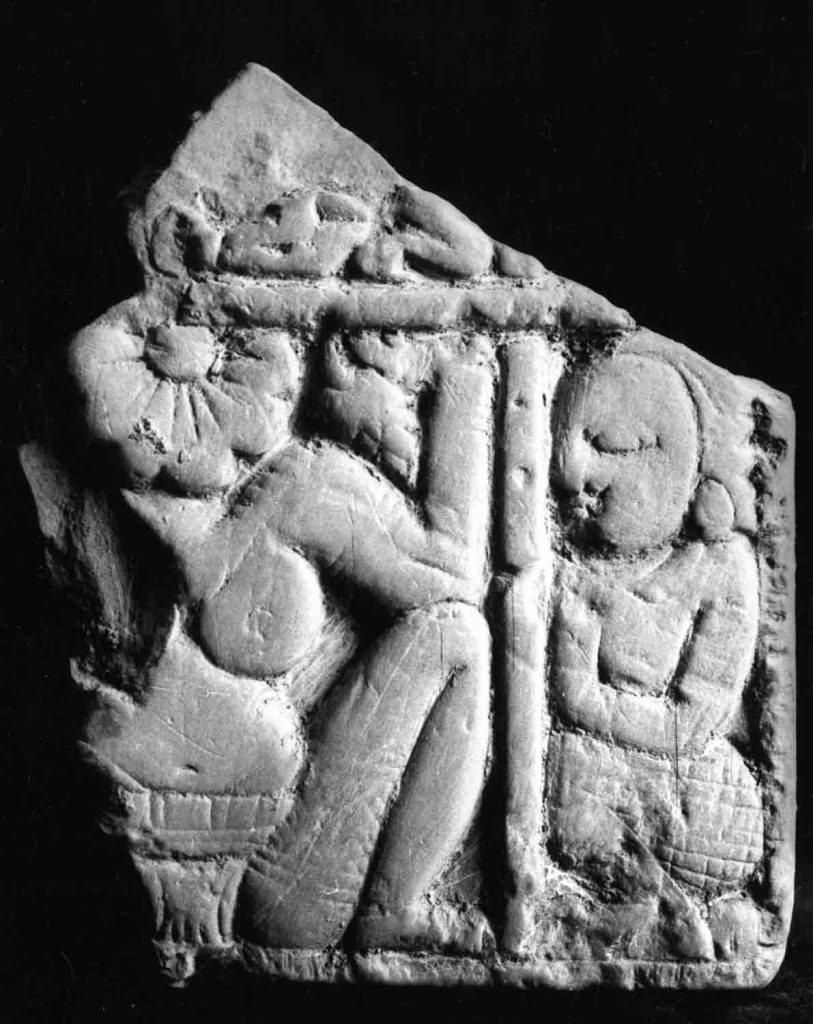

Goddess Lajja Gauri is associated with fertility and abundance, and is identifiable by her squatting uttanapad birth-giving position. She is often represented in ancient Maharashtrian art with a lotus-head, however there are also depictions that represent her with a human head, or no head at all. Lajja Gauri is associated with the earliest forms of Indian art, and can be found throughout the Indian subcontinent. Images of the Egyptian goddess Baubo that exhibit the same visual conventions and iconography as Lajja Gauri have also been uncovered from Ptolemeic Egypt. This resemblance indicates one such possible link between Maharashtra and Roman Egypt.

Zoomorphism & Composite Beings

Lid decorated with female Sphinx head, Ter, Osmanabad, Maharashtra, India, ca. 100-299 CE, Terracotta, #11237.

The earliest depictions of the Sphinx, a winged woman-lion hybrid, are found in Egypt as early as the third millennium BCE. In Ter, a terracotta Sphinx that functioned as a lid for a ceramic vessel was unearthed. This Sphinx figure illustrates the connection between Maharashtra and Egypt. The materiality of this Sphinx vessel indicates that it may have been produced in Maharashtra. Likewise, the figure is relatively crude compared to the Egyptian Sphinxes. As such, this figurine may been produced by local artisans in Maharashtra based on Sphinx figures they came into contact with via trade with Ptolemaic Egypt.

For millennia, animals have served both utilitarian and ritual purposes. The representations of animals in art is one such way that a society’s understanding of animals in relation to humans may be interpreted. In the case of Ter and Paithan, the animal artifacts unearthed indicate that animals were integral to ritual, trade, militarism, and more. A variety of animal and composite animal-human figurines have been discovered at these Maharashtrian sites. In addition to what they communicate about animals in these ancient societies, these animal figurines also provide evidence of contact between Maharashtra and the rest of the ancient world.

The highlights of this assemblage include a Sphinx ceramic lid, a centaur amulet, numerous equestrian statuettes, children’s animal toys, and composite animal-human figurines. This assemblage features stylistic connections to cultures of the Mediterranean, Near East, and Northern Steppe, as well as the retention of aesthetics local to the Indian Subcontinent. As a result, a degree of cultural syncretism may be sensed through the melding of these very distinct artistic traditions. Similar finds from Ptolemaic Egypt, the Saka nomads of Northern China, and Mathura demonstrate the dissemination and evolution of these visual forms.

Equestrian Statuettes are intimately associated with the Greco-Roman artistic tradition. In Imperial Rome, the commission of an equestrian statue was considered to be the highest of honors for the depicted, and was often displayed in public squares and buildings. Smaller equestrian statues were also produced from cheaper materials such as terracotta for plebeian audiences. These miniature equestrian statues may have served as toys, votives, and amulets. In Maharashtra, the assemblage at Paithan unveiled numerous equestrian statuettes depicting soldiers and merchants on elephants and horses. These Maharashtrian figurines provide a glimpse into the militarism and trade of the period.

The Makara is a legendary sea creature that finds its roots in Hindu mythology as the vehicle for the river goddess Ganga. Over time, Makara was incorporated into Buddhist lore, and also became symbolic of seafaring and maritime trade. The image of the ferocious Makara sea monster appears in a variety of mediums including ceramics, sculpture, and painting, and was used as an apotropaic symbol, or protective charm, for sailors along the Silk Route. Makara toys such as the one found at Ter can also be found throughout the Indian Sub-continent at sites such as Mathura and Kausambi, among other locales throughout the ancient world.

Nandi is the bovine steed of the Hindu god Shiva. Nandi is identifiable by the humped back, horns, and hanging skin on the neck. Depictions of Nandi can be found across the Indian Sub-continent, such as in the carvings of the rock-cut temples of Ellora, and even coins and amulets. The Nandi terracotta figurines excavated from Ter include both toy and votive forms. The Bull chariot toy served a recreational function similar to that of the Makara toys, which may be ascertained based on the hole through the center, which would have allowed two wheels to be attached. The more stoic representations of Nandi were likely used for ritual and cult purposes, and may even seek to evoke the image of a particular religious statue.

The creation of the Sphinx figure by the Egyptians was not the only instance of a composite human-animal figure in Ancient Eurasia. In fact, many variations of human and animal interactions were captured in the art of Maharashtra. The coupling of human and animal traits can often be associated with the divinity of a figure. For instance, the image of the Cobra King features an anthropomorphic head with a crown flanked by five hooded cobras. The cobras in this case are not harming the figure, but instead represent an instance of human-animal cooperation and communication which can also be observed in the winged figure with the cobra hair. Divine encounters and relationships between humans and animals in ancient art often represent the power and spiritual threshold of the figure.

Molding

Clay art, specifically terracotta art, remains among the most common art forms found in the ancient Maharashrian sites of Ter and Paithan. The ubiquity of this medium may be indicative of its utility, availability, cultural significance, and the preferences of consumers and artists. Indeed, terracotta was among the most affordable materials as it did not require a pure soil matrix unlike other ceramic types such as porcelain. The availability of suitable clay and relatively low-cost of terracotta has led to the notion that it was primarily a plebian artform. It is also worth noting that terracotta likely embodied ritualistic and symbolic significance as well, as many votives found at temple sites throughout the ancient world are often terracotta.

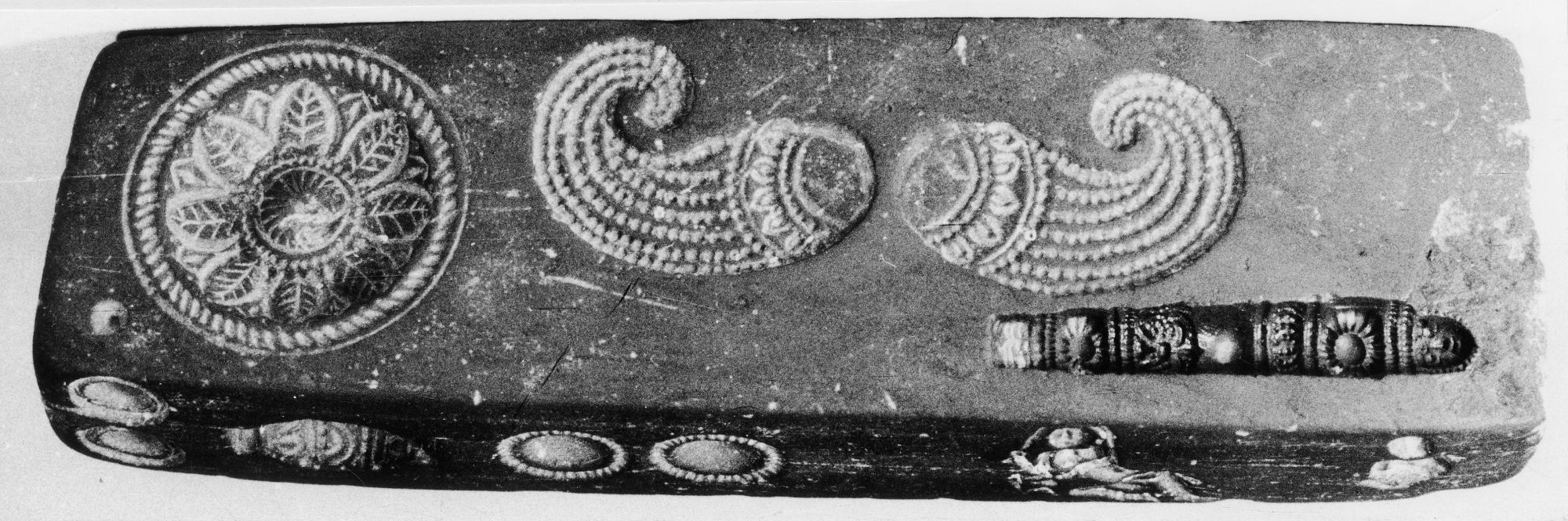

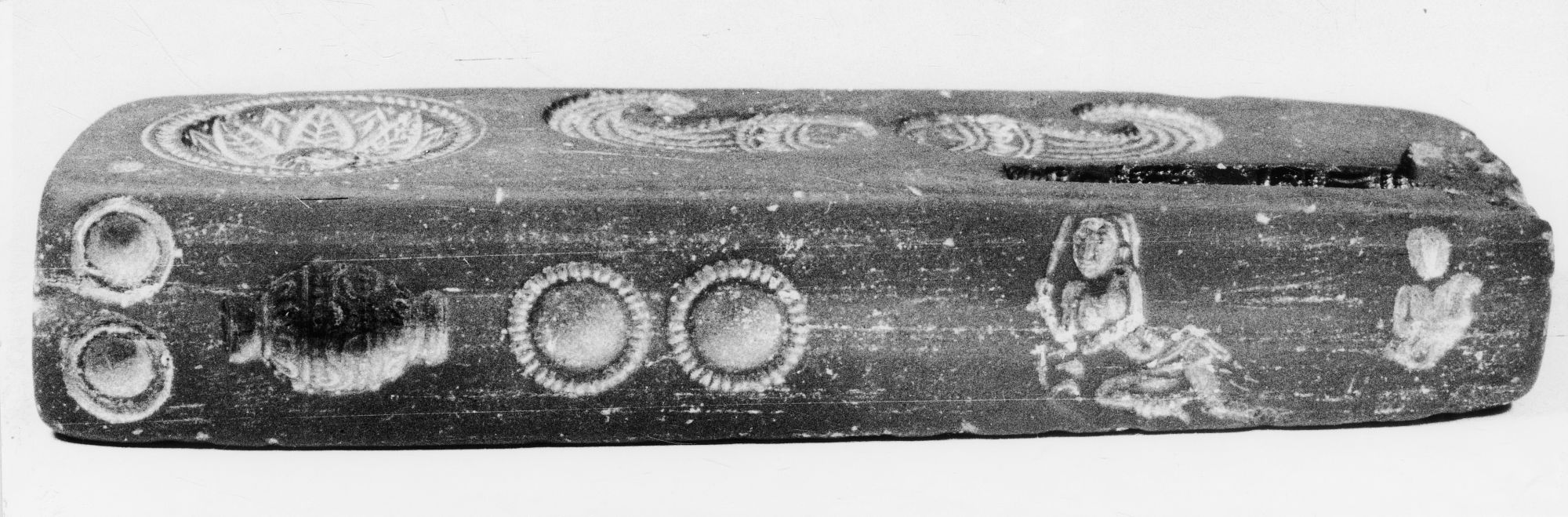

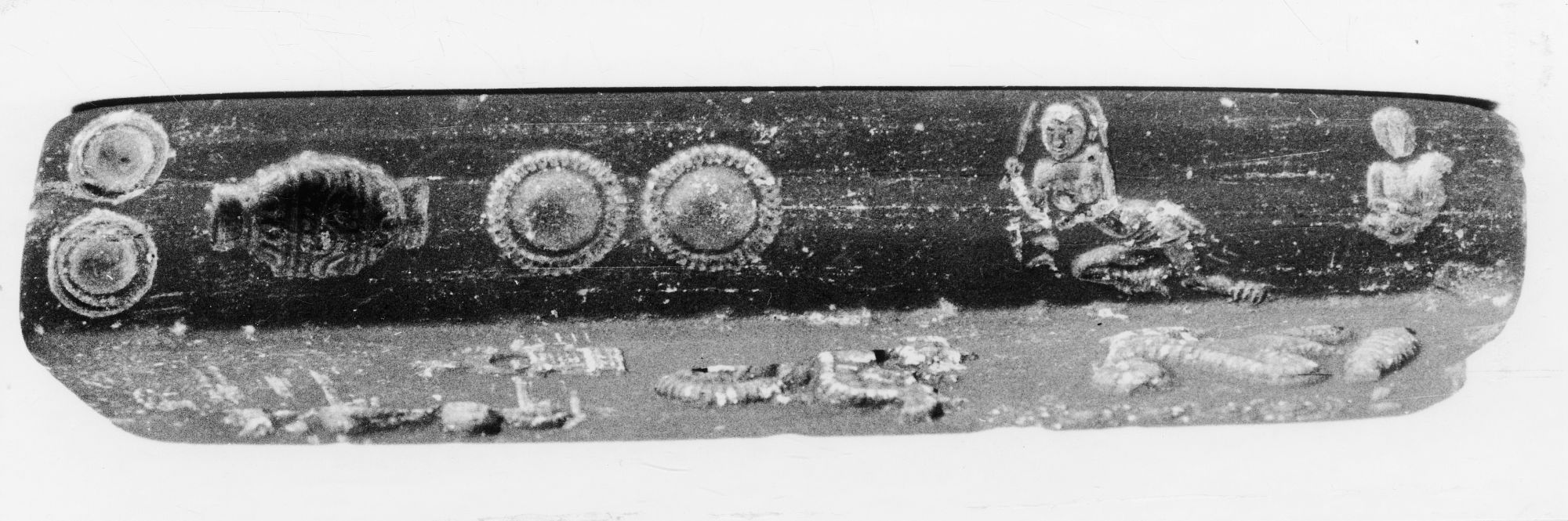

The earliest forms of terracotta art were hand-shaped, while later techniques involved a mold that impresses a design onto a slab of clay followed by firing. Beginning in the 3rd century BCE, evidence of the double-mold technique began to emerge in Maharashtra. This technique utilized a front and back mold to create a double-sided design. Remains of both single and double-molds and the art they produced have been discovered at Ter and Paithan. Not only do molds indicate a process of standardization and commercialization in the context of Silk Route trade, but they also provide insight into the dissemination and evolution of terracotta as an art form.

As trade heightened between the 3rd century BCE and 3rd century CE, so too did the production of trading goods. Ancient Maharashtra was well known for its textiles as well as its terracotta wares. As such, production techniques evolved in order to meet the increasing demand for these items. For terracotta art in the Ancient World, the mold was the foundation of production, as it allowed for the standardization of designs as well as a streamlined production process as opposed to hand-shaped ceramics. Molds also provided a source of inspiration for artists as they were disseminated across Eurasia.

Numerous molds were discovered among the assemblages at Ter and Paithan. These molds included impressions used for fertility figurines, amulets, coins, and more. Many of the molds from these Maharashtrian sites are fall into the double-mold design. The double mold involves two molds which are used to create a three-dimensional figure with a front, back, and sides. This molding technique is different than earlier methods of molding which included stamping and or hand-shaping. The images housed in these molds also provide a glimpse into some of the figures and motifs that were being in-demand during this period.

One of the natural consequences of increased trade and exchange in Maharashtra was the increased foreign demand for locally-produced goods. In this way, the terracotta art produced in Ter and Paithan may be read as a reflection of demands from overseas, particularly those of Imperial Rome. Alternatively, there is also evidence of another trend during this time-period in the Mediterranean wherein molded vessels were purposefully altered in order to reflect a more hand-made appearance. In this way, the taste of consumers for “hand-made” or “unique” vessels was continuously being negotiated with the production techniques preferred by and available to artisans.

The double-mold technique represents a particularly contentious area in the history of ceramics in Eurasia. The emergence of double-mold technology in the Mediterranean, Near East, Indian Sub-continent, and East Asia has raised questions as to the origin of this production practice. It should be noted, however, that the independent invention of this technology in each of these societies is very possible. Variations of the double-mold technique include the double-molded vessels from Corinth in the Greco-Roman Mediterranean. The megarian bowl from Corinth is one example where a mold-made vessel was altered in order to look like a hand-shaped vessel. Similarly the terracotta soldiers of Qin Shi Huangdi were made using double-molds and then fitted together using pipe-fitting technology, but fitted with a variety of accessories to produce an illusion of verisimilitude.

Seals, Amulets & Medallions

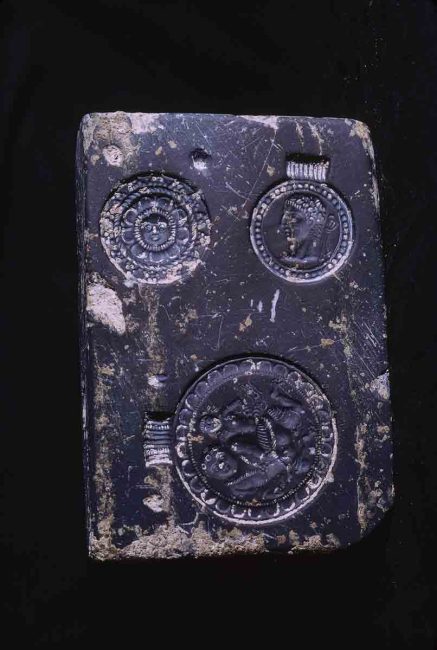

The hoard of seals and amulets at Ter and Paithan are among the most significant finds of these sites. Not only do these medallions indicate activities associated with trade, exchange, and political domain, but they also represent another such proxy by which artistic creolization in Maharashtra may have occurred.

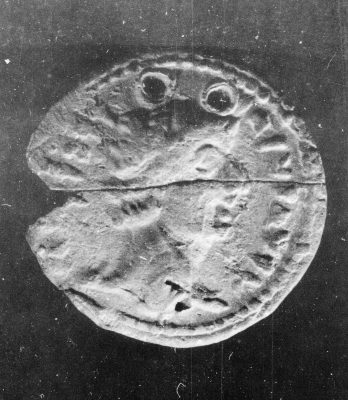

The most common types of medallions in this assemblage include Greco-Roman bullae, Nandi amulets, and amulets depicting Goddess Gajalakshmi. The consistency of the medallion designs in this collection indicates that there were standardized methods of production taking place.

In the case of Ter and Paithan, the presence of amulets (bullae) and seals bearing both local and foreign imagery suggests that Maharashtra was both a venue of production for these medallions, as well as a trading center where foreign medallions were brought and circulated. The medallions found in Maharashtra are almost exclusively made of terracotta, which points to yet another instance where foreign visual types were applied to local media.

The bulla is a type of amulet that was given to Greek and Roman children as a protective emblem. Some were filled with precious metals or semi-precious stones. The typical Greco-Roman bulla was fashioned out of a precious metal or metal alloy, and feature an exterior design. These bulla were also produced with a hollow cylindrical attachment which would have been used to secure a string or chain for the wearer to keep around their neck. Numerous terracotta fragments were unearthed from Ter and Paithan that exhibit an identical design with a hollow appendage. Many of these terracotta bulla also feature images that are comparable to those of the Greco-Roman bulla.

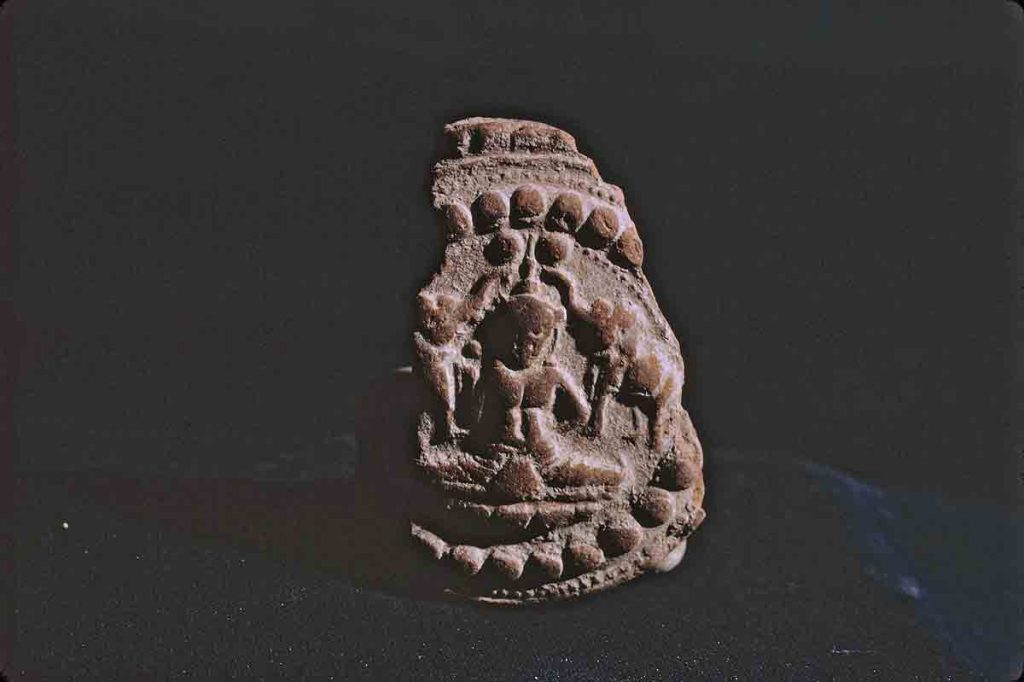

The Nandi amulets from Ter and Paithan come in the form of double-mold amulets and stamped medallions. Both types are of a terracotta medium. The circular Nandi medallions may have served as protective or spiritual emblems. On the other hand, the detailed bovine-shaped Nandi amulets may have been used as votive objects for spiritual offerings. Terracotta was a popular medium for votive and sacrificial objects because it was relatively cheap to make and as such more likely to be sacrificed than objects of a more expensive materiality. Moreover, some versions of votive offering included the breaking of the object, and terracotta would have been relatively easily broken for the purpose of this ritual.

Amulets and bullae representing the Hindu goddess Gajalaksmi were found at Ter. These images of Gajalaksmi flanked by two elephants are remarkable similar, and indicate that homogenous, if not identical, molds were used in their production. One of the Gajalaksmi images is being used for a bullae based on the hollow appendage, while the other lacks the appendage but exhibits an identical image. Another bulla features an elephant that is also mold-made, and features similar circular border as observed in the Gajalaksmi amulets.

Uncovered from Paithan, this amulet features a Leogrphy on the front and a floral motif on the back. The design of this amulet includes a small appendage with a hole similar to the design of the Roman Bulla. The leogryph is a mythical animal with origins in the Near East and Mediterranean regions. Its appearance in this terracotta amulet is another such example of the cross-cultural contact between these distant regions. The rear design features a flower that is remarkably similar in style to this rosette pendant. The small dots decorating both amulets may be an imitation of the granulation metallurgy technique that is associated with the Gupta Dynasty.

Conclusion

Clay is a people’s art, and shows how transculturalism was taking place at an everyday level across the ancient world. This exhibition showcased a variety of religious icons, both human and animal, amulets, medallions, and the molds that were used to make these objects. Each category looked at contemporaneous examples made using the same technology in the regions with which India was trading. The assemblages highlighted in this exhibition allow us to study the intricate social, economic, and cultural connections between India’s Maharashtra region and the rest of the ancient world. Particular parallels have been drawn between the art of the Indian Sub-continent and Ptolemaic Egypt, as well as the rest of the Roman Empire. By way of highlighting these artifacts and their connotations of agency, transculturalism, and creolization, it becomes increasingly possible to cultivate a narrative in which societies such as Satavahana and Ptolemaic Egypt are recognized with the same degree of cultural and artistic agency as Imperial Rome. By extension, the way in which societies such as the Satavahanas and Ptolemies exacted influence upon Roman culture may also be ascertained.

Bibliography

Recommended Readings

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Museum of Afghanistan, British Museum, Kolhapur Town Hall Museum, Allahabad Museum, and American Institute of India Studies' Center for Art and Archaeology for providing the images for this exhibition. Thank you to AIIS Director Dr. Purnima Mehta and Dr. Vandana Sinha, Director at the Center for Art and Archaeology, for providing the opportunity and resources that made this exhibition possible. A special thank you to Dr. Naman Ahuja at Jawaharlal Nehru University for advising me throughout the curation of this exhibition.

Ava Bush

Ava is a graduate student in the Regional Studies East Asia A.M. program at Harvard University. She is the recipient of the Albert and Teruko Craig Fellowship for Japanese Studies at the Harvard Reischauer Institute. In addition to her work at the AIIS, Ava has curated the show “Monochromes” at the New Orleans Museum of Art, and has also completed curatorial work at the Gitter-Yelen Collection of Japanese Art and the Newcomb Art Museum at Tulane University. Ava’s research interests include Buddhist Art, pre-modern Japanese painting, artistic creolization, and Ainu Art and Archaeology.