The Great Monastery of Nālandā was one of ancient India’s greatest cultural institutions. The monastery was a complex of Buddhist monastic dwellings and temples. It functioned as a prominent place of Buddhist learning and teaching from at least the 5th to the 12th Century. It was noteworthy not just for its immense size but also for the considerable number of resident monks who studied and taught there. According to different accounts by travellers who visited Nalanda, there were around 3000-10,000 monks residing at the monastery.

This virtual exhibition aims to provide a brief but comprehensive understanding of the monastery’s history and its excavated remains, using a critical assessment of the archaeological, art-historical, and textual sources. The visual basis for this virtual exhibit is indebted to the remarkable collection of images captured by Dr. Frederick Asher during his extensive research visits to the Nalanda excavation site.

The origin of the monastery is shrouded in myths and mystery. Buddhist religious narratives attribute the founding of the monastery to the Mauryan emperor Ashoka. It is believed that it began as a modest monastery and gained popularity and status only in the 5th century CE onwards. Over time, it became one of the largest and most widely acclaimed monastic universities in the world attracting students from different parts of the world including Korea, Tibet, and China. One of the most popular narratives about how the monastery began is mentioned in the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang’s account of Nālandā. He writes that the land on which Nālandā was built was previously a mango grove which was purchased by 500 merchants for 100 million gold coins. The merchants then gifted the mango grove to the Buddha where the Buddha preached for three months. After the Buddha’s Mahaparinirvana, King Shakraditya (Kumaragupta I) selected this land as a sacred spot and constructed a monastery which went on to become the Nālandā.

From the 5th century until the 12th century, the monastery enjoyed its heyday under the patronage of various dynasties such as the Guptas, the Palas, as well as from rich lay individuals and families. During this period, the monastery was believed to have housed some of the most influential and learned Buddhist philosophers and scholars such as Shilabhadra, Nagarjuna, Shantideva, Shantarakshita, etc. However, after the 12th century CE, the monastery experienced a gradual decline, leading to its burial under soil and evaporation from collective memory.

Sources on Nalanda Mahavihara

Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang who visited the Nalanda Mahavihara in the 7th Century CE. This is an image constructed in front of the Xuanzang Memorial Hall at Nalanda.

Our current understanding of Nālandā relies heavily on two main sources: the writings of Chinese and Tibetan monks who visited the monastery during its period of operation to study Buddhism, and the discoveries made during excavations at the Nālandā site, including the information derived from the inscriptions and the architectural remains. These sources provide valuable insights into the renowned monastery. Unfortunately, there are no records found of any writings by student monks residing at the monastery describing everyday life at Nālandā Mahavihara. Any such writings on every day life by the resident monks are believed to have been destroyed by the effects of geographical time and pressure.

Therefore, the primary basis through which the Nālandā archaeological site was identified in the late 19th century was through the descriptions provided by the Chinese writer Xuanzang. The authenticity of the site was later confirmed by the inscriptions found on sealings at Nālandā. The most extensive name of the monastery is found in a sealing inscription in eighth century script which reads srī-Nālandā-Mahāvihārīyāryabhikṣusaṃghasya (“of the noble monastic community of the Great Monastery of Nālandā”).

Excavations at Nalanda Site

To understand the history of Nālandā, Alexander Cunningham, the founder of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) referred to Chinese sources. Based on the descriptions provided by Xuanzang, Cunningham identified the monuments and the remains at the Nālandā site. Before Cunningham, there were other explorers such as Buchanan Hamilton and Markham Kittoe. A M Broadley, the Deputy Magistrate of Bihar district also excavated at the site in October 1872.

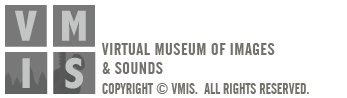

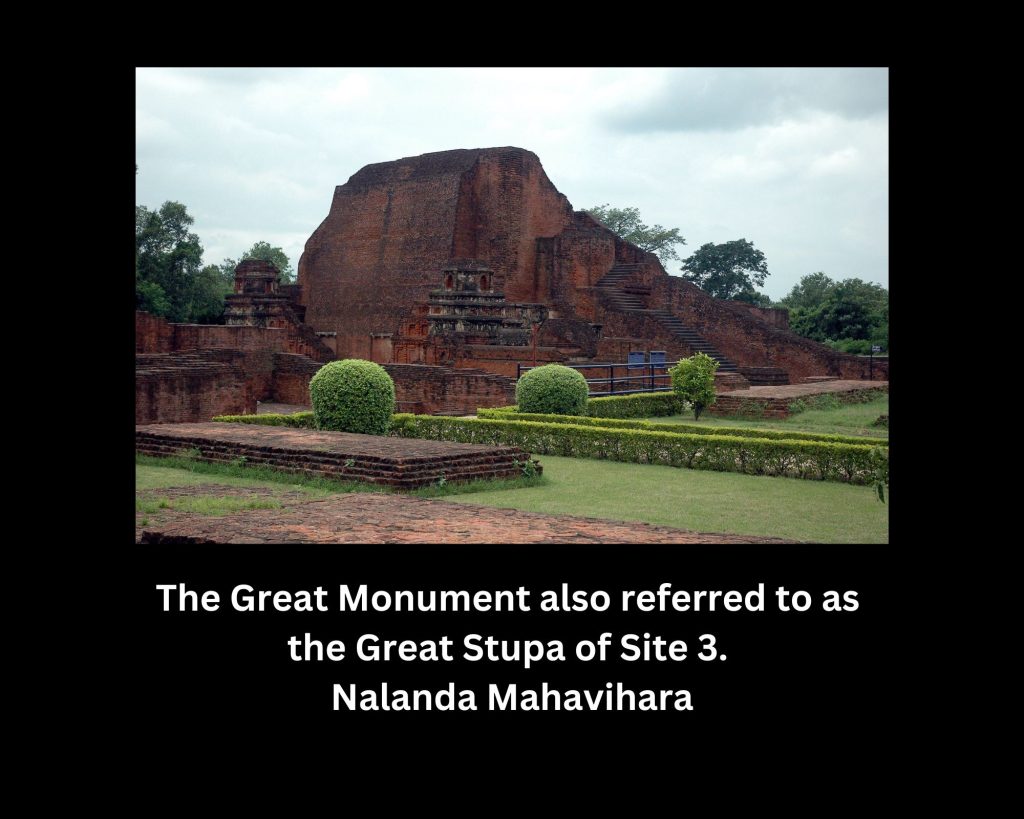

The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) formally undertook two excavations at Nālandā first from 1915 – 1937, and again from 1974 – 82. The excavations revealed the remains of some five temples, eleven monastic dwellings, and an enormous structure at the southern end. The dwellings face westward towards the temple and the temples face east towards the monastic dwellings. The most iconic monument excavated from the Nālandā site is the one known as the Great Stupa or the Great Monument of Site 3. This structure is made like the other structures with brick and stucco adornment. A staircase leads to the top of the structure where a small shrine was located. The stucco figures of the monument and its subsidiary towers date to the 7th century.

The identity or the purpose of this great stupa is uncertain however many consider the stupa base to be the location of the Nālandā’s library. This imagination is based on the writings of the Tibetan monk Taranatha composed long after the site was abandoned. In these sources, the Tibetan monk refers to three buildings (Ratnasagara, Ratnodhati, and Ratnaranjhaka) which functions as a library known as Dharmaganja at the Nālandā.

Origin of the Name Nalanda

Nālandā has been attributed with various origin stories in the writings of Chinese sources. One such tale recounts the existence of a pond within a mango grove that was acquired by 500 merchants and offered to the Buddha. In this pond resided a serpent known as Nālandā, which eventually lent its name to the monastery.

Another narrative is derived from the Jataka tales wherein the Buddha, in one of his past lives, reigned as a compassionate king at the site of Nalanda. Renowned for his immense generosity, the king was called ‘the Insatiable Almsgiver,’ which inspired the Tang Chinese name for Nālandā – Shiwuyan.

In the accounts of Faxian, another Chinese traveller who visited Nalanda during the 5th century CE, a different story unfolds. It suggests that Sariputra, one of the Buddha’s closest disciples, was born and later passed away in a village named Nala. A stupa was erected at the location of his cremation, and over time, Ashoka built a temple there, which gradually evolved into the renowned Nalanda Monastery.

Other accounts suggest that the name Nalanda is derived from the long stalk grass named Nalaka, which grows abundantly in the area.

These diverse explanations in the Chinese writings offer intriguing insights into the origin and significance of the name and the rich historical and cultural heritage associated with Nālandā.

Nalanda's Decline

From the 12th Century onwards, the Nālandā monastery gradually declined in status and also in the scope of its operation. There weren’t any one specific reasons for the decline of the monastery. The decline actually co-incided with a lot of other developments taking place in north India at the time such as the military invasions of north India by foreign invaders, the resurgence of Brahmanical Hinduism, etc.

One of the most often cited reason for the decline of Nalanda is the military invasion conducted by the Afghan military commander Bakhtiyar Khilji in about 1193 CE. This claim is based on the writings of the Persian historian Minhaj al-Siraj in his literary work titled Tabaqat-i-nasri. In that, Minhaj writes that Khilji attacked the fortified city of Bihar considered to be present day Bihar Sharif. However, it was not a first-hand account as Minhaj writes that this information was provided to him by two soldiers who participated in the attack. Based on this report, historians assume that Bakhtiyar Khilji then proceeded to destroy Nālandā from Bihar Sharif. However, Minhaj has not explicitly claimed that Khilji has attacked Nālandā.

However, it is undeniable that Khilji’s attack on Bihar Sharif and the nearby areas had an adverse effect on the region including Nālandā. Nālandā, as a monastery dedicated to learning and teaching, was completely dependent on the surrounding area to maintain their way of life. Khilji’s invasion also could have ended the Pala dynasty’s support to the monastery. So, although there is no direct evidence that Khilji attacked Nālandā, the monastery suffered immensely from Khilji’s military invasion of the region. It is also to be kept in mind that the motivating factor behind Khilji and his soldier’s military invasion were not religious persecution and iconoclasm but rather loot, plunder, and acquisition of land just like any other military action at that period of time.

Archaeological evidence does reveal extensive fire damage at the monastery, with charred bricks and melted materials found. Some believe Khilji caused the fire that damaged the monastery, but Asher suggests accidental causes like oil lamps, commonly used for illumination at that time. He has explained that similar incidents of accidental fire have occurred globally, leading to reconstruction.

Patrons of Nalanda Mahavihara

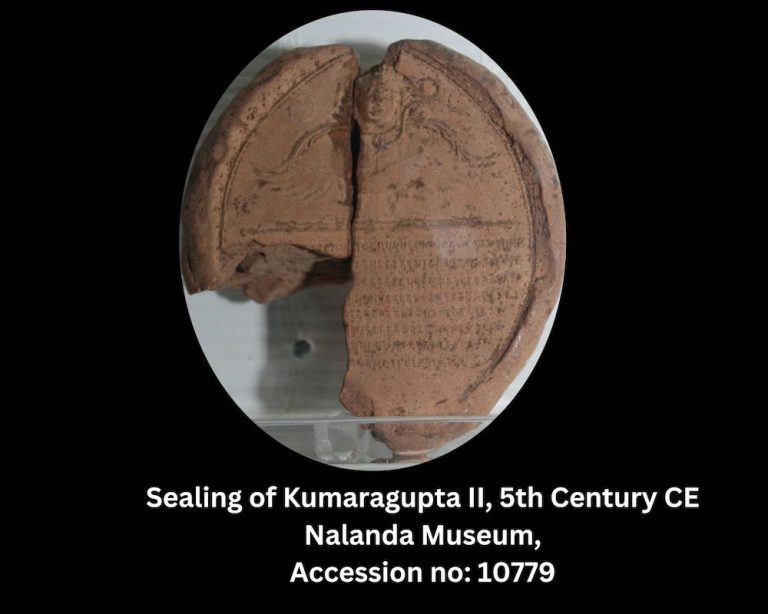

The most well-known royal patrons of the Nālandā monastery were the kings of the Gupta dynasty. That is largely because some 26 Gupta seals have been found during excavation at the Nālandā site. These seals are imagined to be attached to royal charters that provide support for the monastery. These seals include seals of Buddhagupta, Narasimha Gupta, Kumaragupta III, and Vainyagupta.

Xuanzang reports that shortly after the Buddha’s death, a king named Shakraditya selected the site and built a monastery on it. Then his successor and son Buddhagupta built another monastery to the south of the original one, while Tathagupta built one to the east and finally King Baladitya built a fourth monastery to the northeast. The Spanish Jesuit priest H. Heras has identified the above four kings as Kumaragupta I, Skandagupta, Purnagupta, and Narshimhagupta respectively.

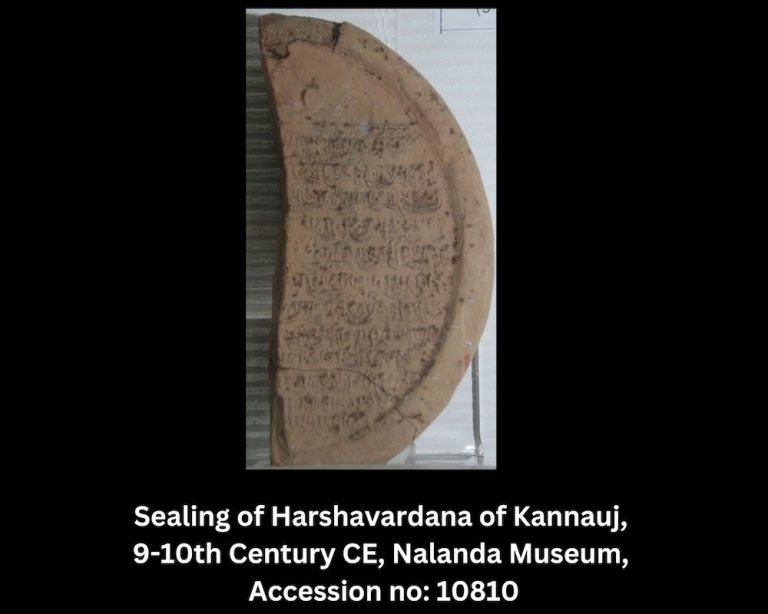

Other patrons of the Nālandā monastery include King Harshavardana of Kannauj who is credited with the reconstruction of Nālandā after its destruction by King Shashanka of Bengal. Seals of King Harshavardana were discovered during excavation indicating his provision of support for the monastery.

At about the same time, other kings also offerings and donations to the monastery. A long copper plate inscription was found during excavation which revealed an endowment towards the monastery from Malada, a minister of King Yashovarmadeva. It is not clear who King Yashovarmadeva was and when was his reign. It is believed from the style of the script used in the inscription that he ruled in the 7th century CE. Other seals also indicate patronage by kings from Assam and the Maukhari dynasty.

Other than the Guptas, the most important dynasty to support the Nālandā monastery was the Pala dynasty. It was also during the reign of the Pala kings (8-12th centuries) that the production of architecture and sculptures made a comeback following a decline in the mid-5th century. That is one reason why almost all of the stone and broken sculptures found at the Nālandā site are dated to the Pala period.

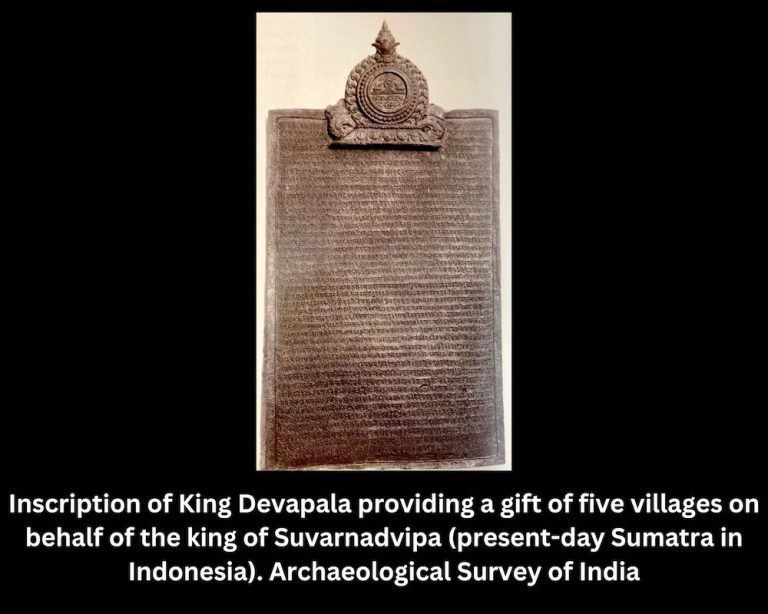

The Pala kings were Buddhists, and remains of copper plates were found at the site that revealed the Pala king Dharmapala gifting a village to the monastery. Another inscription found at the site claims that King Devapala built a monastery and gifted five villages to the monastery on behalf of Balaputra, king of Suvarnadvipa (present dau Sumatra, Indonesia). This is also the only indication of international patronage for Nālandā. However, from the archaeological remains and the inscriptions, there isn’t any record to indicate a foreign presence, unlike Bodh Gaya where pilgrims have recorded their visits and repairs. It is assumed to be because Nālandā was associated with learning and not generally open to everyone.

How did the Monastery Sustain itself?

Remains of burnt rice dated to the 10th Century CE found near Monastery 1 during excavations at Nalanda. Nalanda Museum, Accession no: 04282

If the reports that there were 3000-10,000 monks at the monastery were accurate, Nālandā must have had a dynamic relationship with the surrounding agricultural region, and not just with the surrounding towns. It is undeniable that the surrounding region prospered substantially from the endowment wealth of the monastery, however Nālandā in turn was also heavily dependent on goods and service from the surrounding region. Monasteries produce scholarship, however they don’t produce any goods or services other than ritual services but were rather exclusively consumers.

Just to feed 3000 monks from Yijing’s estimate, food alone would have been a huge enterprise.

If each monk ate even half a kilogram of food per day, it would require 1.5 tons of food to feed 3000 monks. That is far more than the surrounding agricultural area could provide. However, we also need to think about the fact that the surrounding area and Magadha in general was a highly fertile region. These areas could produce as many as three crops per year, reducing the need to bring food from other faraway places. In fact, one reason for the success of Nālandā monastery is attributed to the region’s ability to supply large amounts of food to large concentrated populations of monks. The area around the monastery was also known for having a number of lakes and water bodies.

Sculptures of Nalanda

Probably the most spectacular of all Nālandā’s sculptures are the stucco images that adorn the Great Monument. Access to the site is now restricted following a night time theft in the 1970s. These stucco images were built during the first half of the 7th century, and was part of the fifth level of reconstruction.

This grouping of the images starts with a Buddha seated with his legs pendant, his hands in the teaching gesture. Some have speculated that this gesture suggests the Buddha’s first teaching at Sarnath. However, instead of the images of the five listeners and two deers that is usually associated with the Buddha’s first sermon, this image is attended by a pair of male figures at each side.

The next figure, from left to right, shows a standing Buddha. His right hand extended downward in Varadamudra although the hand is now missing. The left hand is holding his outer garment at shoulder level. This image is imagined to depict the scene from the Jataka tales where Dipankara, a former Buddha,

Particularly the scene where he was walking on a muddy road when a devout Brahman approached him and laid his long hair on the ground so that Dipankara could walk without muddying his feet. Dipankara then predicted that this Brahman would later be reborn in the future as the Shakyamuni Buddha.

The next image shows a standing Avalokiteshvara, perhaps one of the most important bodhisattvas in East Asian Buddhism. It is recognisable from the lotus that he is holding in his left hand and the seated Buddha image in his headdress.

The final figure in this grouping shows the Buddha with his begging bowl. The pose and the style are very similar to the image of the Dipankara. The scene is imagined to represent the Buddha’s son Rahula seeking his inheritance, Rahula being the small figure to the right supported by his mother Yashodhara. The begging bowl symbolises inheritance, and this scene is witnessed by the Buddha’s disciple Ananda on the right.

Who Made the Sculptures?

Some writers imagine that the monks of the monastery as the artists and sculptors who made the carvings, paintings and the stucco images. However, there is no evidence that the monks that were at the monastery came there for anything other than for teaching and study. The real sculptors were almost surely professionals who worked at the site when specific projects were undertaken and then moved on. It is assumed that they may have worked under the supervision of a monk who conceived the overall layout of a building or the order of the sculptured images. The actual sculptors could be lay artists who may be were not even Buddhists.

There are also suggestions that these sculptors who built the stucco images could be the descendants of the sculptors who built the sculptures at the Sarnath temple. That is imagined to be so because the slender, sensuous image style of the sculptures so closely resembles the sculptures at Sarnath dating to the 5th century CE. So, it is assumed that when Nālandā started to receive resources under the leadership of King Harshavardhana, these sculptors moved eastward from Sarnath to Nālandā in the 7th century onwards.

A stucco image of the Bodhisattva Manjushri in its original form (left) and after a theft that took place in the 1970s (right).

Bronzes of Nalanda

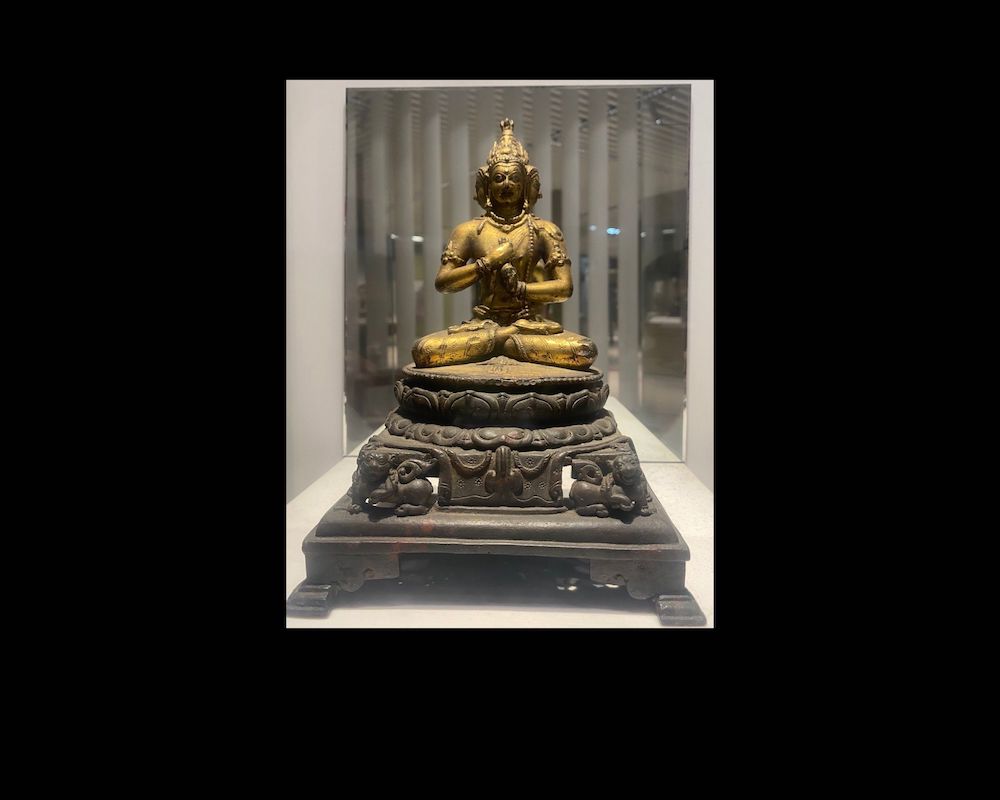

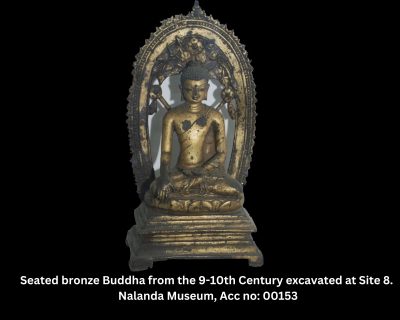

Nālandā as an institute of higher Buddhist learning is well-known and celebrated. However, one lesser-known fact about the Nālandā monastery is that it was also a flourishing centre of metal works, especially bronze. More than five hundred bronze images were found from the Nālandā site during excavations. The bronze sculptures were mostly small in size and found almost exclusively in the monastic dwellings suggesting that they were used by individual monks. The bronze images depict mostly the Buddha and some Mahayana Buddhist deities such as Avalokiteshwara, Manjushri, etc. Today, most of these bronze images are in the Nālandā Museum, with several also in the Patna Museum, the National Museum, and the Indian Museum.

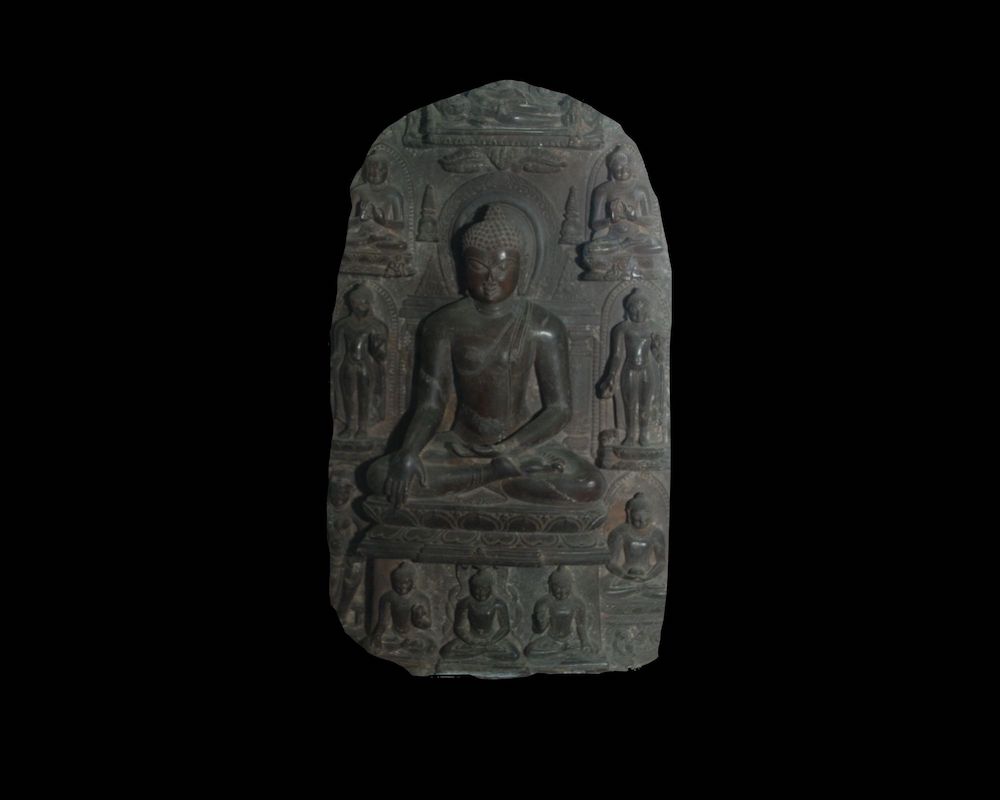

As discussed earlier, almost all of the bronze images and sculptures found at Nālandā during excavations were dated to the 8th century or later, i.e., during the period of the Pala dynasty. This is the case with almost all the bronze sculptures found in all parts of eastern India. This is generally assumed to be so because the Pala dynasty facilitated easier and safer access to the copper deposits in Ghatshila in present-day Jharkhand.

Who created these bronze images?

As was the case with stucco images and stone sculptures of Nālandā, the artists who made the bronze images are also considered to be professionals. We learn from the Tibetan lama Taranath who wrote a treatise titled History of Buddhism in India, in 1608. In this history, he cites a father and son duo named Dhiman and Bhitpalo, who were skilled artists that lived during the reigns of kings Dharmapala and Devapala. Based on this citation, many scholars have taken this father-son duo to be the founders of the bronze metallurgical works in Nālandā.

The seated Buddha with the hand extended downward in the earth touching gesture is 30 cm in height. Leaves over the head suggest the Bodhi tree beneath which the Buddha achieved enlightenment indicating that this image represents the Buddha overcoming Mara at Bodh Gaya. Emerging from the image’s shoulders sprues through which the molten metal flowed from the seated figure to the surrounding halo. This figure is believed to be dated to the 8th century because of the similarity with other such images both bronze and stone assigned to this date.

Seated Avalokiteshwara: This image is discovered along with the bronze seated Buddha image. It is considered to be a companion piece but it is more elaborate in its design, so it is considered to be made by a different sculptor.

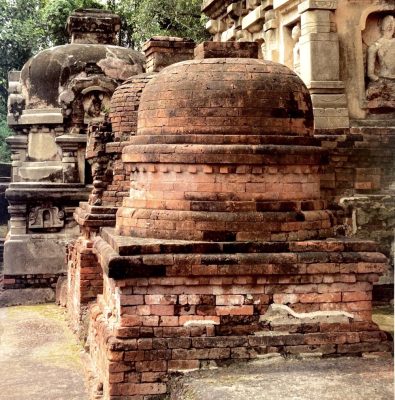

Stupas of Nalanda

Miniature stupas in front of the temple of Site 12.

During excavations at the Nālandā site, many miniature stupas were found. Most of these stupas were found in front of the temple at site 12 and also near the Great Monument. Some of these stupas were made from solid blocks of stone, others from bricks. The brick stupas were originally believed to be covered in stucco with stucco images. However, these are not well preserved whereas the ones in stone are well preserved.

Buddhist stupas are generally shaped like a bell. It has a semi-circular structure atop a cylindrical drum with a canopy on top of it all. It is supposed to represent the Buddha seated in his meditative state with an umbrella on top. Traditionally, stupas have a reliquary function. They act as a shrine that contains sacred objects or relics of a holy person. The stone stupas found at the site of the Nālandā were built from solid blocks of rock, so they cant contain a relic. Some also suggest (based on Shobhana Gokhale’s observation at Kanheri caves near Mumbai) that these stupas have a funerary function, such as commemorating monks associated with the Nālandā, ones who spent long periods of time at Nālandā or those who died while at the monastery.

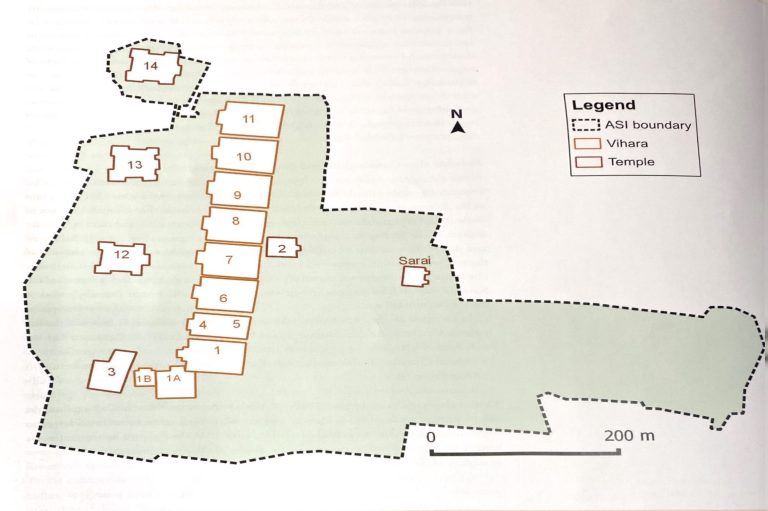

Nalanda as an Active Site of Worship

When we think about Nalanda today, we usually imagine ruins of old temples and monasteries. Some may also think about how invaders supposedly destroyed this great cultural centre of ancient India. Although it is true that the physical structures of Nalanda Mahavihara no longer exist, its history didn’t really end in 1193. Rather, it continues to have an impact even today in the way that people imagine and practice Buddhism. The knowledge and teachings that originated there are still prevalent through the networks that it has established. For instance, the philosophical traditions established by Nalanda scholars, such as Nagarjuna, Shantarakshita, Shantideva, etc., continue to influence the teachings of contemporary Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. Even in terms of religious practice, there are remnants of Buddhist religious activities that have continued to this day around Nalanda. Just outside of Nalanda, there is a modern temple known locally as the Black Buddha Temple. This black Buddha image is supposed to be gifted by a teli (oil trader) to the Mahavihara. Similarly, in Jagdishpur near Nalanda, there is another Buddha statue that is worshipped as the Jagdishpur Buddha by the locals. In Bargaon, there is a Surya temple that houses a crowned Buddha image which is worshipped along with the images of the other deities. These practices showcase a continuity of religious activity at Nalanda even after the great Mahavihara declined after the 12th century.

Acknowledgements

This exhibition is drawn from the images compiled by the late Dr Frederick Asher during his research visits to the Nalanda Archaeological site in Bihar. I would like to thank Dr Sraman Mukherjee for sharing his expertise on the history of Nalanda Mahavihara with me during this two-month program. I would also like to thank the AIIS for giving me this opportunity especially Dr. Elise Auerbach, Mrs. Purnima Mehta, and Dr. Vandana Sinha.

About the Curator

Jamphel Shonu is currently a PhD student in the Department of History at Pennsylvania State University. His research interests include Tibetan history, trans-Himalayan connections in the early modern and modern eras, and the history of Tibetan Buddhism. He was earlier the editor of Tibet.net and the Tibetan Bulletin magazine published by the Central Tibetan Administration in Dharamshala, Himachal Pradesh.