- Home

- Uncategorized

- Introduction: Inhabiting the Sacred

Introduction: Inhabiting the Sacred

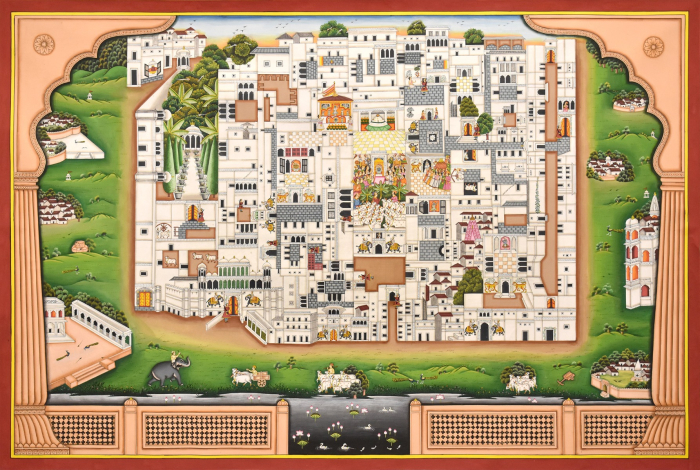

In the state of Rajasthan, perched atop a hill and nestled in a bed of labyrinthine streets and bustling markets, lives a God. Having manifested himself at the top of the sacred mount Govardhan in the form of Krishna as a seven year-old boy, he spent many happy days among the people of the Vraj in Uttar Pradesh, swiping handfuls of ghee from village stores and hiding the clothes of bathing maidens. He earned the undying worship of many by lifting the mountain he was born from above his head, shielding the villagers from the tempestuous rains of the king of devas. A massively popular sect of Hinduism evolved around him, in which individuals would cultivate a deeply personal, loving, and intimate relationship with him, fashioning themselves after his lover Radha or foster-mother Yashoda. As legend states, he enjoyed many centuries of worship in Vridavan before having to flee from the threat of iconoclastic conquest. While on their way further South away from the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, the wheels of the chariot bearing Shrinathji got stuck in mud. His followers understood this as a sign that the strong willed deity wished to go no further, and built the town of Nathdwara—the ‘Portal to the Lord’—around that very spot.

Eager to see and be seen by a God, I, like millions of others every year, made the trip myself to Shrinathji’s home. As an art historian, there were countless reasons to go—the hand-painted cloths called pichwais that decorated his shrine and set the stage for worship, the fantastic displays of food and toys they’d offer to the God seven times a day to suit his various moods, and of course the temple itself, built more like a mansion than a sanctum so as to suit the luxurious needs of a living god. And yet, the most important thing I learned from this trip had much less to do with the scholarly information that could eventually find itself in a book, and much more with the nearly indescribable intimacy and electricity of sacred space.

At the gates to the temple complex, all electronics were confiscated as I entered the first courtyard. Unassuming at first, with hardly a hint that this may contain a luxurious mansion with a powerful god, I skirted the perimeter of a pavilion, weaving between merchants selling vibrant garlands made for offerings, their wares filling the air with the intoxicating aroma of jasmine and marigold. Though some stopped to buy something, most dodged the outstretched hands that were all but hidden by piling mounds of fresh flowers. The crowd surged forward in a jumbled mass until we were filtered into lines by metal fences like those in amusement parks. With every twist and turn revealing nothing more than lightly tanned plaster walls, I began to wonder when the supposed ‘mansion’ would appear—then, right on cue with a melodrama befitting the confident young Lord, I found myself in front of a corbeated archway nearly three meters tall, flanked on either side by rich, cobalt-blue elephants with two princely riders atop each.

Ascending the steps and passing through, the sounds of worship begin to filter through the din of conversation, distant drums, flutes, and singing promising a celebration of the divine soon to come. Many press on towards the main sanctum to receive darshan and see Shrinathji, though others are engaged in a diverse variety of auspicious activities. Swept along by the tide, I find myself gratefully receiving a bindi from the orange, kumkum-coloured finger of a priest, just before I join the others in pressing my head against a wall anointed with swastikas. Almost before I can register everything that’s happening, the wave heaves forward, leaving me in a choked, thin hallway with even more coiling lines. A final moment of suspense before turning into the sanctum, the sounds of the courtyard and beyond gradually fade away and are replaced by the raucous din of whatever lies beyond the last turn. At last, myself and many others flow into Shrinathji’s home. Hardly knowing how, I find myself perched on wooden stands in the back of the cordoned off area. Straining my neck, I look beyond the pulsating shoulders of the crowd, past the empty space that lies between us and the Lord, through the heavy doors thrown open for just these thirty minutes, and lock eyes with the beautiful and merciful Shrinathji.

For me, and I’m sure many others, those few minutes in front of a God strip you of all thoughts, all fears, and fill your heart with pure feeling. The experience is so deeply sensual that the conscious makes way for the felt—voices of all ages sing in unison, old men with rasping baritones and young children with squealing sopranos; the fragrance of sandalwood and jasmine fills the air with a scent so thick and warm your lungs feel physically full; bodies push against your own, absorbing you into the throng of worshippers as the air vibrates with energy; and of course, perhaps most importantly of all, you see the God in all their glory. Just as I’ve seen in so many pichwais, Shrinathji stands with his right hand on his hip and his left held aloft, mimicking the same motion he made to save his beloved people from Indra’s wrath. His dark black skin is dressed in striking white cottons draped carefully across his body, while massive garlands nearly obscure his entire chest. And behind all of this, to set the stage for worship and create an infinite variety of imagined spaces, hangs the painted pichwais. Through cows and rolling hills, rows of milkmaids and winding rivers, and countless other scenes, these mobile and versatile cloths are changed regularly to evoke particular moods and environments for followers to embody their love for Shrinathji.

“Vajra asked: O sinless one : Kindly tell me (about) the making the form of deities, so that the inner form remains according to the śāstras, in the figure manifest (the deity). [1]

Mārkaṇḍeya answered : O king : He who does not know the Citra-sutram (canon of painting) very well, can never understand the characteristics of the image. [2]

Vajra inquires : O progenitor of Bhṛgu race : Kindly explain to me very clearly the canon of painting, because one who knows the canon of painting, knows the characters of images. [3]

Mārkaṇḍeya replied. It is very difficult to know the canon of painting, without knowing the canon of dance, because, O king ! in both, the world is to be imitated (or represented). [4]

Vajra inquired : O, the twice-born : kindly explain to me the canon of dance and then be kind to speak about those of painting; because one who knows the science of dance, knows painting. [5]

Mārkaṇḍeya replied : Dance is difficult to be understood by one, who does not know instrumental music (Ātodya). Without instrumental music there cannot be dancing. [6]

Vajra asked : O the knower of principles ! Kindly elucidate the canon of the instrumental music and then you will speak about the canon of dance, because O excellent Bhārgava ! When the instrumental music is properly understood, one understands dance. [7]

Mārkaṇḍeya answered : Without vocal music, it is not possible to know instrumental music. One who knows the science of vocal music, knows everything according to the rules. [8]

— Vishnudharmottara Purana, Khanda III, Adhāya II, Verses 1-8

Though a fair distance away from South India, where most of this exhibition will be taking place, this story reveals much about the lived experience of sacred space and the relationships between the various mediums in South Asian art. The energy of Nathdwara, though unique in character, is common in conception; temples serve as a locus for the arts in India, bearing elaborate carvings, sprawling mandapas filled with dancers, and often, hangings detailing legends important to the deity the sanctum hosts. No matter the scale, from the towering gopurams of Srirangam Temple, to the humble withering stones of a village shrine, these sacred spaces serve to bring together communities and their art.

The congregation of the seemingly disparate—of textile with architecture, of the hunched elderly with the strapping youth—is enabled by the common goal of everyone and everything within these spaces: to revel in the love and grace of the divine. Consecrated icons, as described by the ancient Sanskritic treatise on the arts, the Vishnudharmottara, “are of supreme importance in the present” age, as their worship confers merit and prosperity upon their audience. Thus, an artist traditionally practices his craft so as to facilitate encounters with the divine by revealing the latent beauty in the world. Regardless of medium, this shared purpose connects all the varied arts of India and reveals their common characteristics and origins. Further, the arts not only share a philosophical framework, but are explicitly connected in their practice. The sage Markandeya warns that to understand images, one must first understand painting; and to understand painting, one must understand dance, and so on. As such, the technique—and therefore formal qualities—of each medium are informed by all the other arts around it.

With this, we return to the temple as the epicenter of the arts in India so that we can begin to dissolve the perceived barriers between different art forms and discover a deeper understanding of their relationship. I hope to demonstrate in this exhibition that textiles and architecture are not only related, but in many ways interdependent in their decorative and conceptual evolution. Both rely on the idea of ‘dressing’ to channel the auspiciousness of the divine—in the case of architecture, stone is dressed through painting and carving, while in textiles, the material itself dresses the body. By utilizing motifs from sacred architecture, textiles are able to confer similar grace to the body that carvings and mandalas afford to temples, as with the geometric designs of the Telia in Andhra Pradesh.

Further, architecture is often constructed and maintained through textiles themselves. Temple hangings like the figural kalamkari of Andhra Pradesh would cover entire walls and act as portable murals to accompany oral performances of legends. As we will see later, even when these narrative textiles find a life of their own beyond the temple premises, they continue to draw their iconography and decoration from sacred architecture, serving to extend the fame of legendary pilgrimage spots by spreading their stories and geographies to distant lands. In this way, the two maintain each other—the textile constructs and reifies the legends that allow temples to draw visitors from across the subcontinent, while temples themselves offer spaces for their use and inspiration for their iconography. Using Andhra Pradesh and nearby regions as a case study, we will discover the beautiful intimacy of the arts in India while revealing the omnipresence of the divine in daily life.

Curator's Note

This exhibition implies a linear progression through the material, moving from the Telia to the figurative kalamkaris. However, this pathway is nothing more than a suggested starting place for viewers. Textiles and sacred spaces are deeply intimate and immediate experiences that demand a personal relationship with the aesthetics in order to fully understand. As such, a self-guided journey through the exhibition is not only possible, but encouraged. Look for connections between the textiles and temples yourself, even beyond those I highlight in my writing. Forging new pathways will put different photos in proximity to each other, allowing for new discoveries and relationships with the material. I strongly encourage you to assert your claim over your experience of this art and make it your own, as that is how these objects and spaces are meant to be experienced. Multiple journeys through the exhibition are also encouraged, as each new pathway will reveal more beauty and meaning in both the selected objects and the art of India at large.

Acknowledgements

A special thank you to Professor Anjan Chakraverty for advising me throughout the duration of the exhibition. It is thanks to his guidance and expertise that this project was able to take shape in the way it did in such a short amount of time. I would also like to thank the American Institute of Indian Studies for allowing access to their impressive and profuse collections of images. Even those not featured in this exhibition were essential to developing my research in a way that would not be possible in any other scenario. Additionally, the director of the Center of Art and Archaeology, Vanda Sinha, deserves special mention for offering unwavering guidance throughout the production of this exhibition, as well as director general Purnima Mehta for making the DIL fellowships logistically possible. Thank you to the Victoria and Albert Museum, British Museum, Royal Ontario Museum, and National Museum of New Delhi for providing many of the images for this exhibition. Finally, a thank you is in order to Professor Jinah Kim of Harvard University, for introducing me to the wonders of South Asian art and advising me continuously as I pursue my passion through this field.