Architectural Dress: The Kalamkaris of Srikalahasti

Introduction

The kalamkaris of Andhra Pradesh defy the perceived boundaries between mediums perhaps more than any other. These cotton cloths are produced using mordant and resist dye methods that are applied directly to the cloth with a kalam, or pen. After a series of dye baths, each adding an additional color and contributing to the painterly qualities of the textiles, they are hung on walls as an accompaniment to oral narrative performances. Made of cloth and decorated like a painting, these hangings operate in a space that is architectural, performative, and painterly, all while leveraging the strengths of textiles. In this section of the exhibition, we will examine how these cloths function as mobile shrines that can extend or even construct their own sacred space. By examining where shared motifs occur in the textile as compared to the temple, we will find that the kalamkaris functionally condense temples into portable objects by mapping key locations within the temple onto analogous areas of the cloth. Finally, some hangings will be found to not only imitate architecture generally, but to refer to specific temples, contributing to the creation of pilgrimage networks. In this way, textiles sustain and inspire architecture as much as they are influenced by it.

Technique

The creation of even a single kalamkari is remarkably complex, with historical accounts listing as many as 26 different steps that are all essential for producing a high quality textile. However, a single glance at a finished kalamkari is enough to dispel any surprise at this fact, as the intricacy of the horizontal narratives and the vibrancy of their rendition could require nothing less than a feat of labor. Though different families and communities have perfected their own variations on the process over countless generations, there remain a number of steps that are more or less universal to the craft. To begin with, the cotton cloth—finely woven so as to allow for a smooth surface for the pen to glide across—must be treated in some way so as to facilitate a clean design with vibrant colors and sharp outlines. Often, this means bleaching the cloth several times in a solution of buffalo milk, dung, and certain plants, then washing and leaving it out to dry in the sun between each treatment. Doing so creates an even surface for the brush while softening the fibers of the cloth so that the dyed colors bind to them more readily.

A brief video that illustrates the treatment of the cloth in preparation for design and dyeing. A man plunges a large bunch of fabric into a metal vat containing a mixture of buffalo milk, dung, and ground fruit. He wrings out the cloth and swirls it around to ensure even treatment.

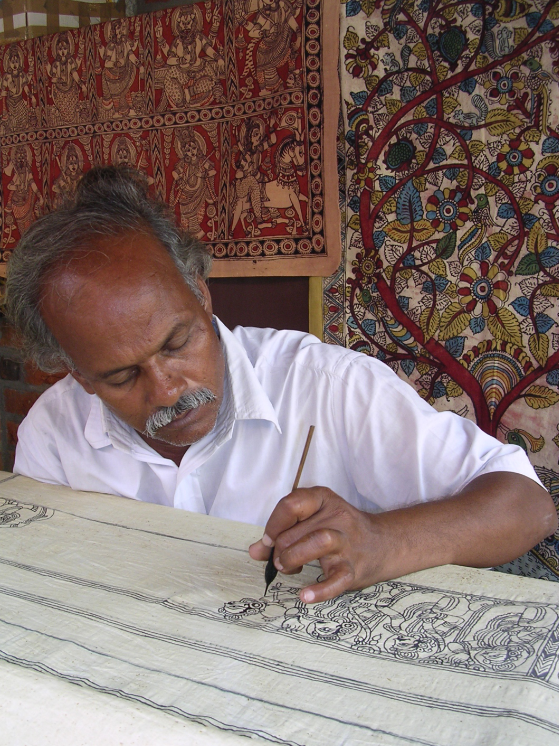

Having prepared the cloth, master designers will sketch the outlines of the composition in charcoal or some other easily washable material. When they’re satisfied with the results, either they or one of their students will go over the tracing with an iron acetate mordant, or a corrosive liquid that allows the black color to fix to the fibers like ink. They do this using a kalam, or pen, that consists of a mass of fibers wound around the end of a rod of bamboo. The artist can control the flow of ink by changing the amount of pressure they apply to this wound mass, allowing for precise, sharp outlines.

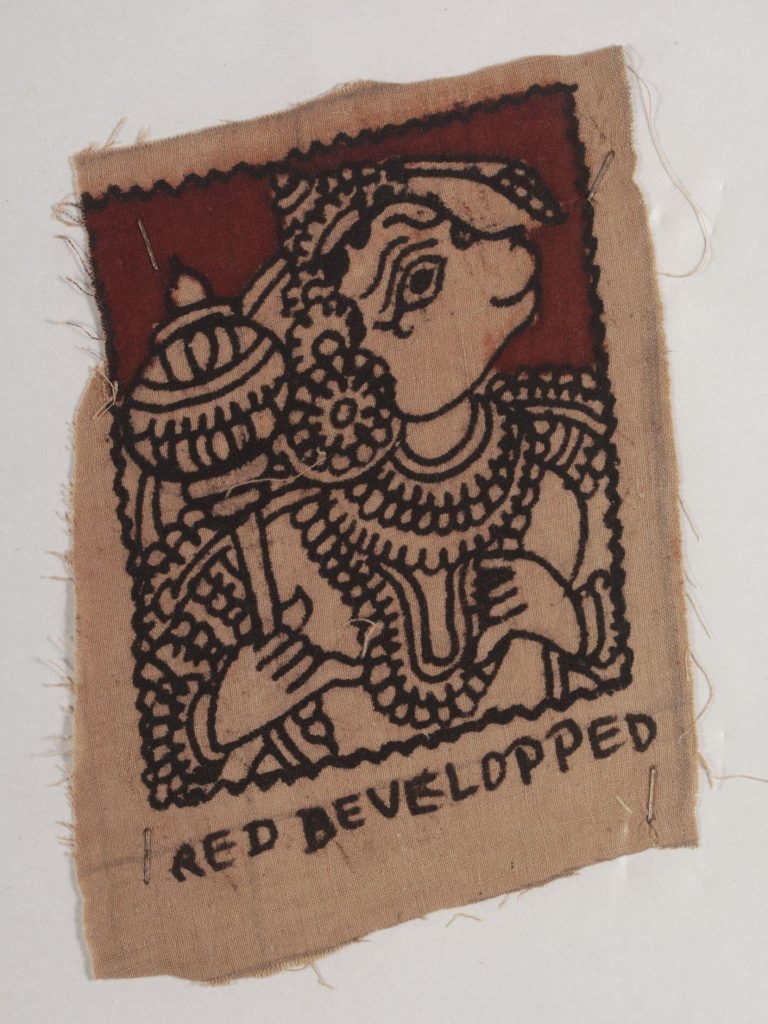

Next, artists will mark the areas for red dye by hand painting alum onto the cloth. This colorless mordant renders those areas susceptible to the red dye, allowing the color to permanently bind to the fibers after being submerged. A wide variety of hues can be achieved by manipulating the amount of mordant applied, how long the cloth is submerged in the vat, and repeated dye baths. Unmarked areas do not take well to the dye and are at most slightly pink following this round of coloring. After a few more washes and some time in the sun, the cloth is once again a pristine white, save for the precise, black outlines and sections of carefully shaped red.

The following step is to dye the areas that must be blue. This is accomplished through a resist dye method that blocks areas from taking unwanted dye, as opposed to applying mordant that will allow color to bind to the fibers. Though many resists are used throughout India, wax is the most common in Andhra Pradesh. Having shielded all but the areas meant to be colored, the cloth is once again submerged in a dye bath, this time composed of the famous indigo plant that produces the rich blues that India is known for. After all of the desired hues are achieved, the now familiar step of washing and bleaching the cloth is repeated. Finally, yellow is hand painted directly onto the surface of the cloth, completing the vibrant, three colored compositions characteristic of Srikalahasti.

In the technique alone, we can already observe many of the material confluences of the kalamkari craft. The methods utilize many of the traditional skills of textile production, including resist and mordant dyeing. However, these practices are changed to mimic the application of paint, using the fine-tipped kalam pen to achieve remarkably graceful and intricate figural designs. Finally, the painterly textile becomes architectural as it is hung on a wall to set the stage for an oral performance of the legends it succinctly narrates in horizontal bands. Even now, it might occur to us that the only other place where so many mediums converge at once is the temple itself. As we will see, this is not coincidental, but a consequence of the relationship between kalamkaris and the temples whose function they attempt to condense and mobilize.

Textile Temples

It is believed that kalamkaris were gradually developed by wandering minstrels who wanted to accompany their narrative performances with visual aides. The composition of these stories was inspired heavily by the painted murals and stone carvings found within temples. However, a textile base was needed to provide the lightweight portability that a traveler would need. A keen eye will notice, however, that the motifs adapted from temple architecture are not chosen randomly, but selected with their original context and purpose in mind. By mapping each motif on the kalamkari to its respective location within a temple, we will find that they are arranged in a manner that reconstructs sacred space on the textile itself. The borders of hangings can be traced to the thresholds of temples with the epicenter of both containing the primary venerated deity, with auspicious narratives occupying the space in between.

Bordering the Divine

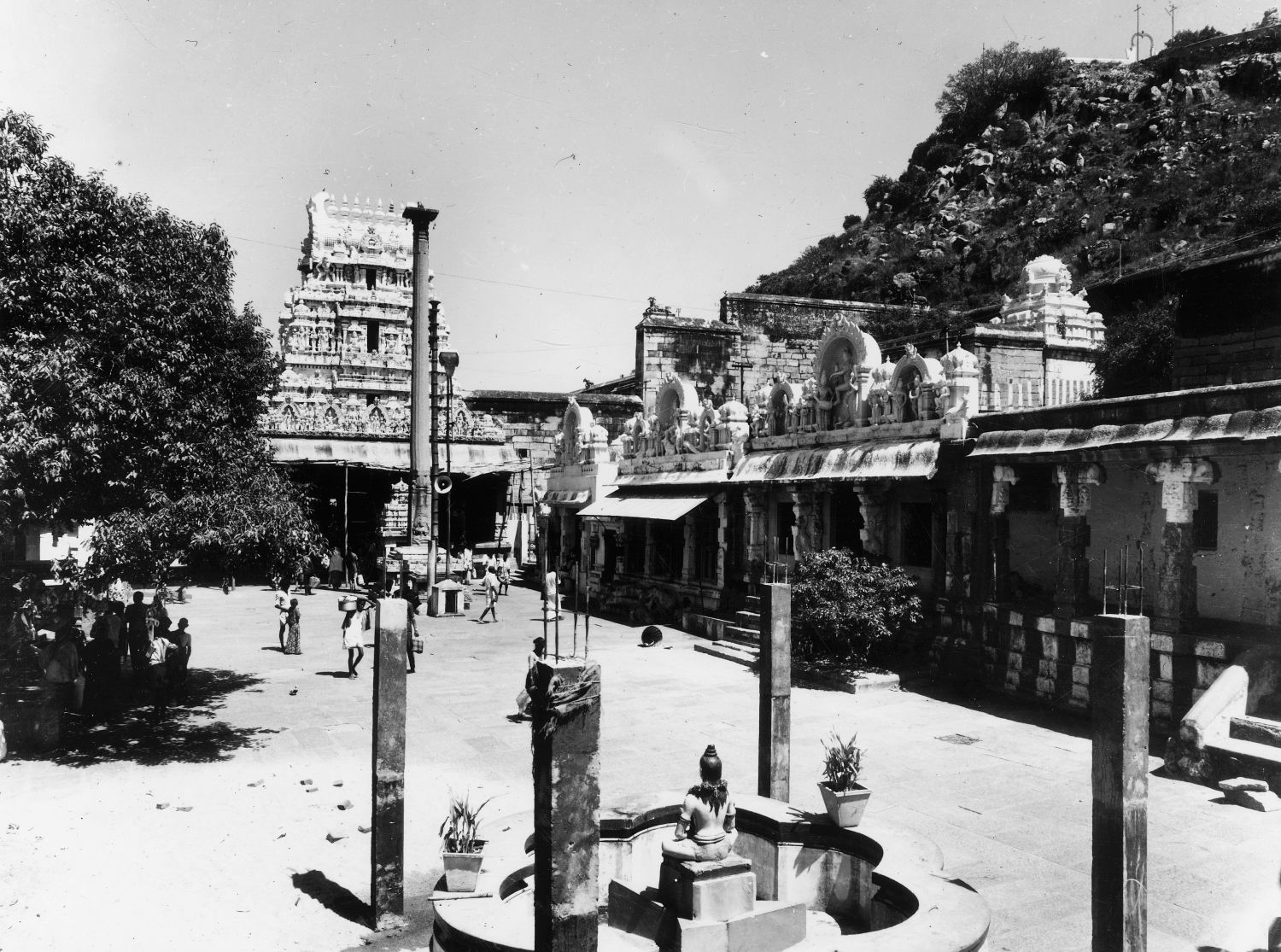

Our journey through the textiles will mirror that of the temple—thus, just as one might stand before the impressive portal to the divine, we will begin by considering the borders of the kalamkaris. What’s more, our initial observations will be grounded in none other than the local temple of Srikalahasti itself, the center of production for many of these works and thus the most likely visual inspiration.

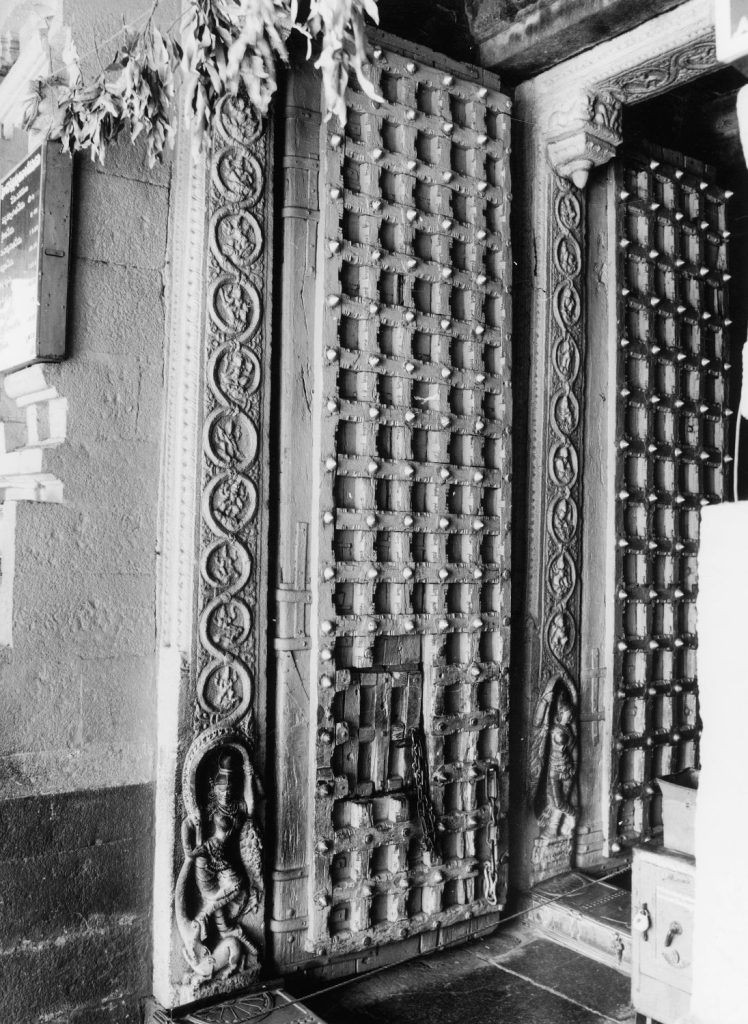

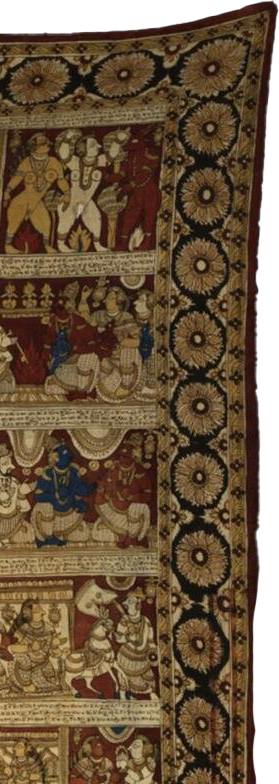

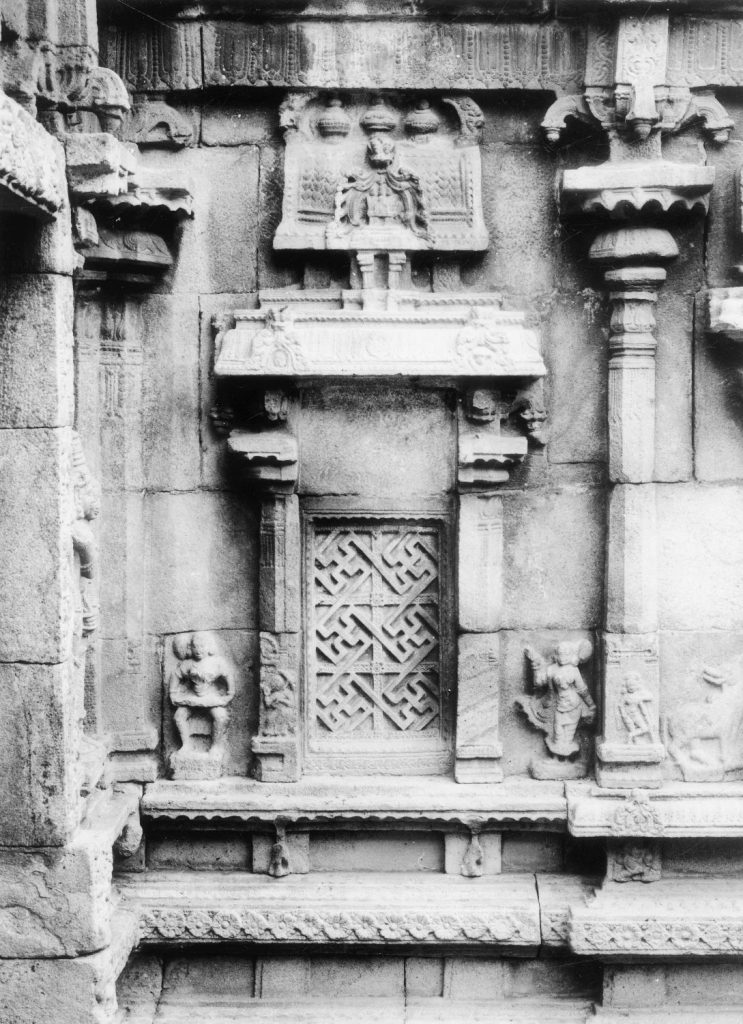

The door jambs of the temple are decorated with coiling creepers that, in shape, look remarkably similar to the series of flowers that adorn the border of many Kalahasti kalamkaris. Further, the motif wraps around the entire portal, containing the entire entrance and acting as a complete threshold, just as the textile motif bounds the interior of the composition.

Of course, it is necessary to acknowledge that the two are not identical—the temple motif features auspicious figures nested within circular vines, while the textile motif is undoubtedly composed of lotuses. This does not discount their potential connection, however. When comparing the details of two different mediums, it is essential to keep in mind the unique material affordances of each. The door jambs, carefully carved in stone on a surface as many as 12 centimeters across and several meters tall, permit much more detail than the thin edges of the kalamkari. As such, the geometry of the motif was maintained while the specifics were adapted to the limits of the medium or artisan. When comparing textile and architecture, it is often the case that abstracted geometries tie the two together.

Within the Divine

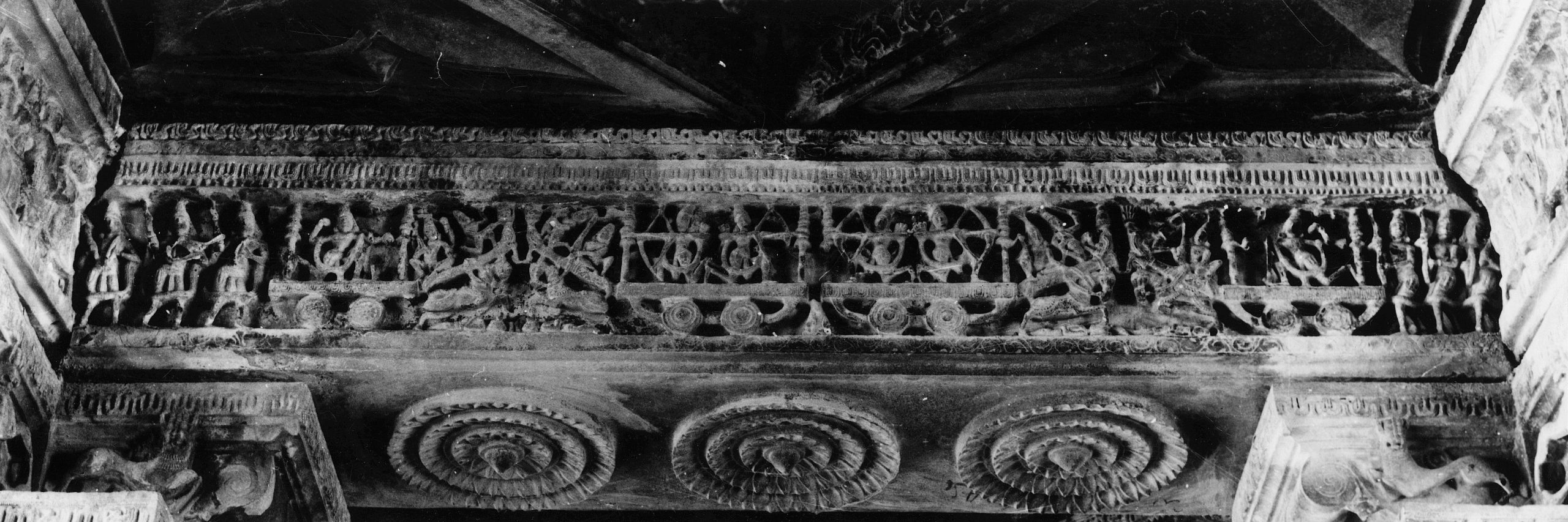

Having entered into the world of the divine, one is hard pressed to find even an inch of stone that isn’t ornamented in some way. Gods, spirits, and plants press in from every side, snaking across brackets and crawling into corners so that as little space as possible is left bare. Though the subjects are diverse, it would not be misguided to say that the vast majority are informed by auspicious narratives. In order to represent the progression of these stories on inert material, artists intuitively grew to favor the horizontal band as a compositional device. Whether representing multiple scenes from an epic like the Ramayana, or else a single moment encapsulating an entire story like the churning of the cosmic ocean, visitors will find legends unfurling lengthwise around the temple. In many cases, however, these scenes may be scattered, with bits and pieces of the story located on lintels, walls, and any other free space in all directions, immersing the viewer in the center of the story. To see this, we will travel to the dilapidated yet graceful Nagulapad Temple in Telangana.

The interior of the temple is composed of square bays whose lintels—the stones above that connect columns—are intricately carved with iconic legends. As one maneuvers from one bay to the next, they will find themselves surrounded on all sides by narrative strips, always in the center of the action. Explore some of the scenes and construct the space in your mind by progressing through the carousel of images below.

When comparing these panels to the narrative strips of the kalamkaris, we can immediately note many compositional similarities. For one, the consistent rectangular shape of the scenes demonstrates a shared approach to narrative construction. Further, both utilize captions to explain what is occurring in the story. Though time has ravaged the paint of Nagulapad, one can still note the writing above the churning of the cosmic ocean and the abduction of Sita by Ravana. The comparison between the abduction scene to a kalamkari from the Victoria and Albert Museum’s collection is particularly enlightening. Both feature a caption specifically above the image and, despite centuries lying between their creation, the illustration of Ravana is similar across the two, with multiple heads and arms arranged in monstrous sequences.

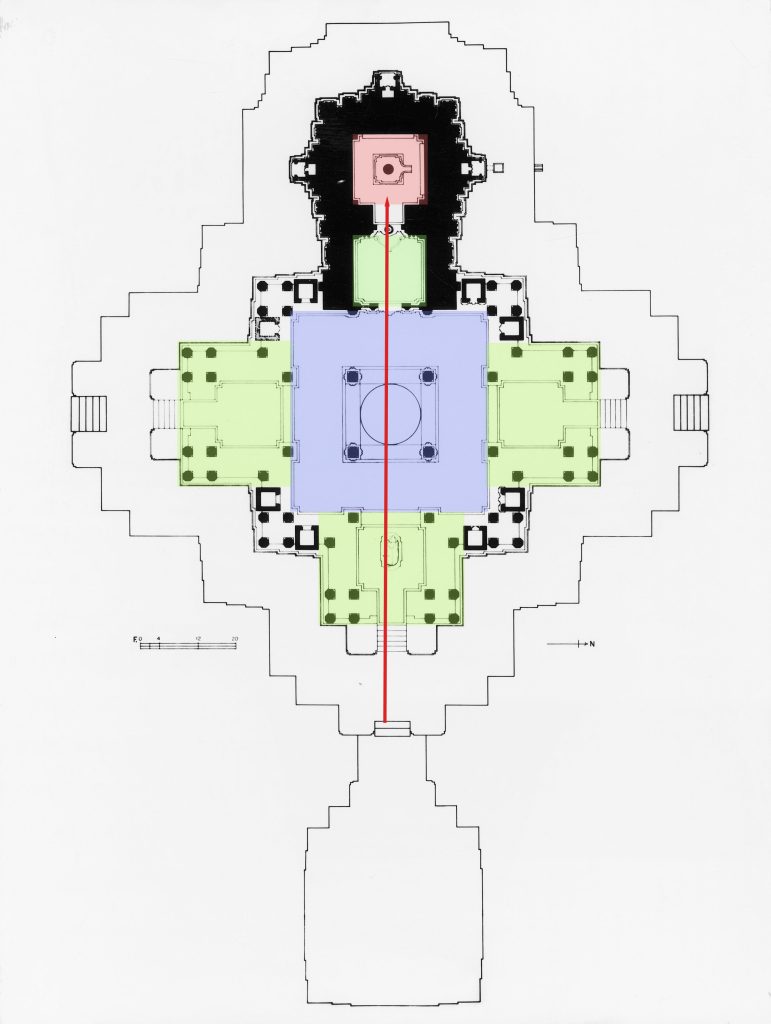

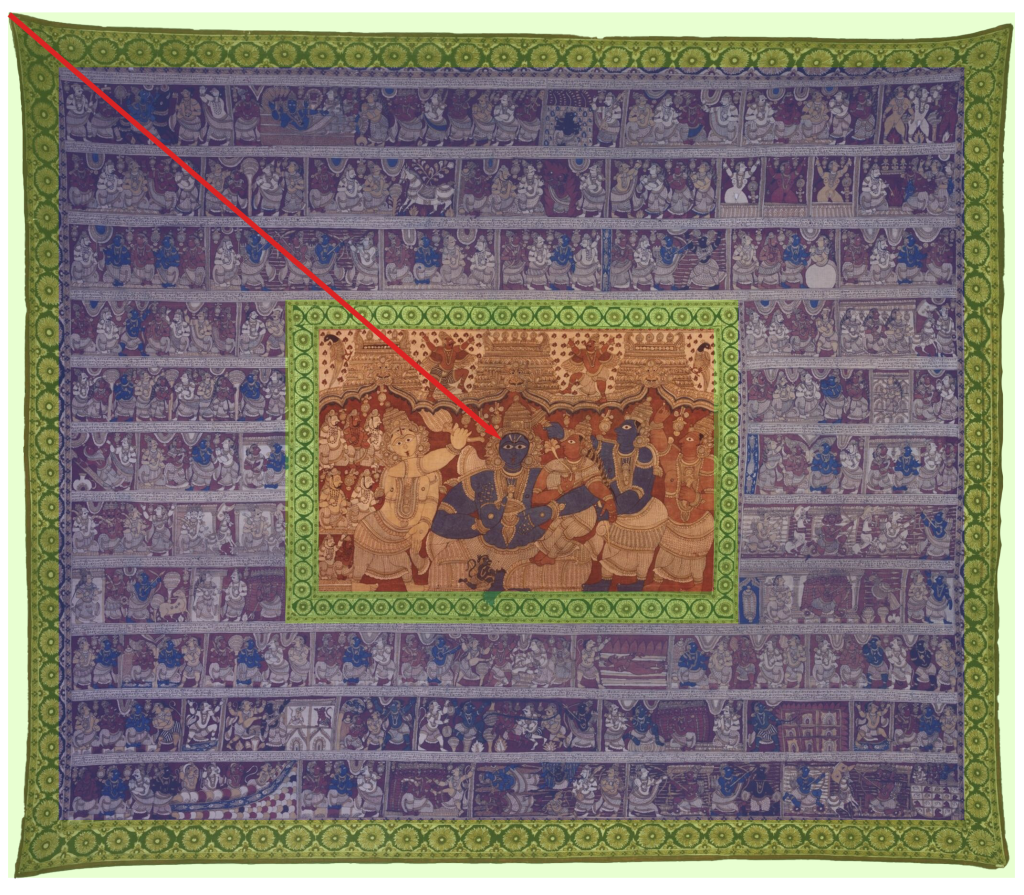

Most, if not all of the narrative content of the temple will lie within the boundaries of the mandapa halls. In other words, these panels can be found beyond the threshold marked by auspicious creeping vines, but before the garbagriha, which contains the primary image of the temple’s venerated deity. The kalamkaris are arranged with the same spatial relationships in mind. The legends lie within the boundaries of the sacred, yet don’t encroach upon the sanctum of the murti. Although the placement has been adapted to a two dimensional space, the outer to inner progression of the textile mirrors that of the temple. One can imagine the carved lintels of Nagulapad being rearranged into stacked bands exactly like the kalamkari without having to change anything about their representation or relationship to the rest of the temple.

The Divinity

After stepping into the realm of the sacred and witnessing the heroic feats of the gods, it is finally time for the devotee to receive darshan in front of the venerated deity. Tucked away in a sanctuary called a garbagriha, the murti, or image of the divinity, is the climax of the religious experience. Standing in front of a God, one can see and be seen by the divine, in turn receiving their grace and power. This section of the temple is usually bereft of narrative content, instead focusing solely on the God and their retinue. The deity faces directly forward with eyes wide open to bear witness to their devotees, occasionally flanked by guardian figures known as dvarapalas or servants waving chowri (fly whisks). Photos are rarely taken of murtis or the garbagriha out of respect to the deity and to protect them from theft, but we can compare this description to the kalamkari and notice some immediate similarities.

Here, Vishnu sits with his arm around his lover Lakshmi with the other held by his side with his hand in abhaya mudra, offering safety and bliss to those who greet him. To the left, a chowri bearer marks his auspiciousness, while above, his vahana (mount) Gardua flies with wings spread wide. Other figures abound, including a slight Hanuman leaping across the bottom. At the center of the textile, just as the temple, lies the God in all their grace and beauty. If we compare the spatial relationships of the different areas of the temple to the relationships between various motifs in the kalamkari, we will find that the progression is maintained exactly.

In light of this, we may consider the kalamkaris to be temple experiences condensed onto mobile pieces of cloth. They not only share motifs, but maintain the spatial relationships between them so that the journey ‘through’ the textile mirrors the progression through temple grounds. A threshold marks the transition into the sacred, a space in which the visitor may marvel at the legendary feats of the gods rendered in horizontal panels. A secondary boundary lies between the interior of the temple and the spiritual center, or the garbagriha with its wide eyed murti. When these cloths are hung, the condensed temple is projected forward as an audience gathers to enjoy the performer’s stories of the Gods. Just as a backdrop to a stage is able to transform the space in front of it, so too can the kalamkaris mobilize and reconstruct temple architecture.

Constructing Sacred Geography

It is clear that the kalamkaris are drawing upon temple architecture to inform both their design and their purpose, serving as a functionally mobile shrine. However, for some the connection goes deeper than a general imitation. Many kalamkaris, particularly those from Srikalahasti, can be shown to allude to specific temples. When this is the case, they are usually referring to famous shrines that are part of a large pilgrimage network. I will demonstrate in this section that by mobilizing the image of specific temples, the kalamkaris help to construct sacred geographies by spreading the legend and image of specific locations. People from far away may be motivated to undergo a trip to the temples they hear about, initiating the cross-continental journeys that eventually lead to the creation of a legendary pilgrimage network.

On a Bed of Snake Hoods

Just South of Andhra Pradesh, in the state of Tamil Nadu, resides the largest temple complex in India. Known as Ranganathaswamy Temple, the site is dedicated to the recumbent figure of Vishnu resting on the serpent Ananta in an eponymous form of the divinity called Ranganatha. Just as Vishnu and the serpent float atop the cosmic ocean, so too do the temple grounds sit atop divine waters, as the site is situated in the center of an island framed by two auspicious rivers. Thanks to its natural environment, architectural beauty, and an abundance of sacred poetry and art celebrating the site, Srirangam has been able to achieve the status of a legendary pilgrimage spot and is one of the most important locations for followers of Vishnu.

According to legend, the temple was created during the earliest stages of the universe, when the various conflicts between asuras and devas brought forth the many aspects of the cosmos. During one such event, Brahma performed severe austerities and won the favor and attention of Vishnu, who appeared before him as Ranganatha, resting within his holy vimana, or vehicle, which would be the temple as we know it today. This holy abode would float down the rivers of time for eons, finding itself at turns within the heavens or lost somewhere on Earth, until it finally alighted upon on the island where it stands even now.

This narrative is helpful for understanding how seemingly incidental aspects of a locations history may in fact be intentional strategies to transform a locale into a pilgrimage destination. The reality of the temple’s construction likely includes many more laborers and fewer gods, thus suggesting that this story was, for one reason or another, created to elevate the status of the temple. This further reveals that pilgrimage networks are not entirely random, but at least partially constructed.

Spreading Legends

The kalamkaris are essential to this process, as they are capable of mobilizing the very architecture whose image must be spread to entice pilgrims. We have already seen how the hangings refer to temples more generally, both in structure and content, but now we will compare a selection of them to Srirangam to see how they might be referring to this site in particular.

Perhaps the most obvious starting place for connecting this to Ranganatha Temple is the fact that Ranganatha himself resides in the center of the hanging. Much like his murti within the garbargriha, he looks towards the viewer as he rests atop the thrice coiled Ananta whose many hoods loom above Vishnu, singing his praises. However, to connect this specifically to Srirangam, we must look for indications of geography and architecture, rather than just iconography and legend.

Much like how the kalamkaris reconstruct key spatial relationships to recreate the temple experience, so too does this hanging reproduce the geography of the island upon the cloth itself. Ranganatha is surrounded by a temple with towering gopurams and impressive shalas, which themselves are contained by two river motifs as indicated by sequences of fish against a background of blue. The fish flow in two, opposing directions, emerging from the left side of the image to meet at the right. This mirrors the flow of the rivers in real life and not only situates the center image as occuring on an island, but even recreates the flow of the two rivers that split upon Srirangam and converge further to the East. In this way the hanging situates the image within a specific location that calls to mind a place that could be none other than Srirangam, offering a geographical specifity to the image that can create associations between this area and the legends depicted elsewhere on the textile.

This cloth not only recreates the geography of Srirangam, but even refers to specific elements of the temple. For one, we find further evidence of the relationship between the border of lotuses on the textiles and the circular creepers on temple portals. As with other entrances in South India that we’ve examined, the door jambs of Ranganathaswamy Temple also feature the creeper motif. In addition to this, we can observe elsewhere on the temple a sequence of circular lotuses almost exactly like those on the border of the kalamkari. Significantly, this occurs on a horizontal section of the wall that has much less space to work with than the large and flat door jambs. Thus, we see the temple itself simplifying the motif to accomodate less space, rather than observing it solely on the textile.

The next feature of note is the similarities between the representations of the gopurams, or towers, on the textile and the temple itself. The South Indian, or Dravidian architectural style can be distinguished from other regional approaches through its pyramidal tower structure wherein in strongly delineated layers are stacked atop one another. A section can be identified by the presence of motifs that repeat vertically—namely, a barrel-shaped vault called a shala. Accordingly, these structures are capped by a spiked shala that gestures towards the skies while marking the crest of the tower. As the largest active temple complex in the world, Srirangam has plenty of examples of these, with each of its dozens of gopurams bearing a similar looking shala crown.

The next feature of note is the similarities between the representations of the gopurams, or towers, on the textile and the temple itself. The South Indian, or Dravidian architectural style can be distinguished from other regional approaches through its pyramidal tower structure wherein in strongly delineated layers are stacked atop one another. A section can be identified by the presence of motifs that repeat vertically—namely, a barrel-shaped vaulted ceiling called a shala. Accordingly, these structures are capped by a spiked shala that gestures towards the skies while marking the crest of the tower. As the largest active temple complex in the world, Srirangam has plenty of examples of these, with each of its dozens of gopurams bearing a similar looking shala crest. As the crowning element, it is natural that this feature becomes symbolic of the entire architecture under a limited visual economy. Thus, we can observe one such shala above the image of Ranganatha on the kalamkari. Though flattened, it is no less recognizable, bearing a horseshoe shape with teardrop-shaped spikes running along its top length. The differences we observe between the full scale representation and its simplification on the kalamkari may once again be attributed to a condensing of form given limited space. What’s more, the same condensed form can be observed on the walls of the temples themselves, demonstrating that this is a symbol of larger architecture utilized by both mediums.

Both designs feature three of the teardrop spikes framed by a curling motif on top of the horseshoe-shaped shala. Additionally, a kirti-mukha, or victorious face, decorates an arch below. On the temple, this is contained within the shala, while on the kalamkari it spreads outwards to contain the image of Ranganatha. This discrepancy makes sense if we consider the shala as it occurs in the textile to be a symbol for the architecture of Ranganathaswamy as a whole—it contains the image in the center just as a temple might contain a stone murti in the garbagriha.

By referring directly to Srirangam rather than more generally to sacred space as a whole, the kalamkari is able to associate the narratives it contains with the location it depicts. As the founding narrative surrounding Srirangam indicates, stories are essential to elevating the mundane to the status of the divine, and beyond that, to the level of the legendary. Textiles like the kalamkari, which can mobilize sacred space in a way that retains key elements of its original location, allow architecture to spread roots across the entire subcontinent. Just as ritual creates reality, these narratives breathe life into architecture and transform stone into the vehicle of the divine. Legend is not incidental, but actively transformative and plays an essential role in constructing archiecture as we know it. Thus, in many ways, architecture relies on textiles like the kalamkari as much as cloths rely on temples. The two mediums not only take inspiration from each other, but construct and reify the other, leveraging material specificities to pursue a common goal of grace, beauty, and auspiciousness.