Auspicious Dress: Ikat Textiles within Andhra Pradesh

Introduction

In a craft known for its complexity and difficulty, ikat weaving still manages to stand out as one of the most impressive textile techniques practiced at any point throughout history. Produced by tie-dying bundles of yarn then carefully arranging them on a loom to create various patterns, ikat garments have been worn and celebrated in India for millenia, with evidence of their use found in the murals of the Buddhist caves at Ajanta. Prized around the world, it is no surprise that this technique has found its way to Andhra Pradesh, both in trade and practice. In this section of the exhibition, we will consider the geometric designs of ikat in South India, examining how these unassuming and simple patterns may actually share inspiration with temple schemes. By invoking similar patterns, these textiles channel the auspiciousness of temple architecture so as to imbue the objects—or people—they dress with divinity.

Technique

This video describes and showcases the modern ikat process of Pochampalli, Andhra Pradesh. Artisans begin by marking a design onto stretched yarn using a pen. Then, rubber or some other resist material is tied around those markings to block pigmentation during the dyeing process. Finally, the tie-dyed strings are woven on a loom to produce the desired pattern.

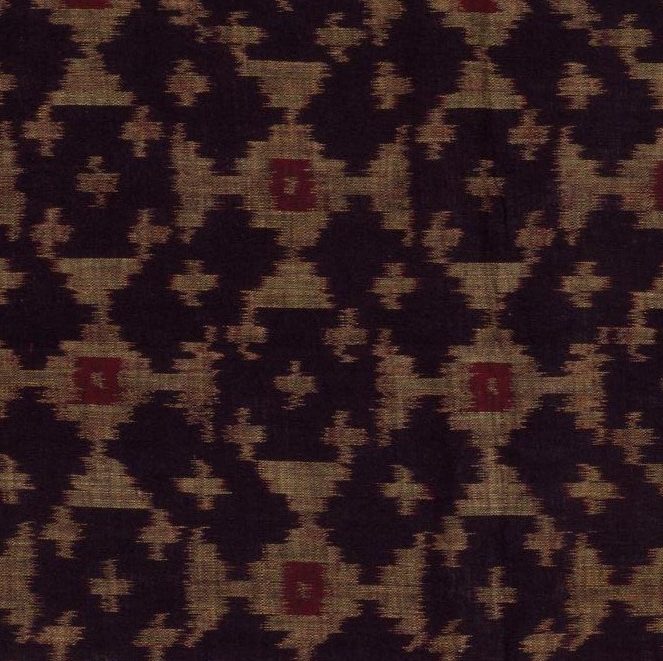

Ikat is a resist-dye method, meaning it utilizes a technique wherein a material is applied to sections of the textile before dyeing so that those areas ‘resist’ pigmentation, resulting in patterns formed by the contrast between dyed and undyed portions. For many, a familiar example of this might be the tie-dyed shirts of childhood arts and crafts. In the case of ikat, however, the resist dye occurs before the construction of the garment itself. The yarn is stretched across a horizontal plane so that artisans may sketch their desired pattern onto the surface of the strings. Then, the strands are collected into bundles and wrapped with rubber or some similar material so as to block those portions from taking the dye. Finally, the colored bundles are taken apart and woven into the predetermined pattern on a loom. As seen in the nearby example, this technique yields geometric designs whose patterns seem to bleed across the fabric, resulting from mild deviations in the placement of individual strands as well as the capillary action of resist dye that allows pigment to suffuse small areas of yarn that were blocked off.

This general approach informs a number of different varieties of ikat, broadly divided into two main approaches: single and double. Plain weave—the basis for all ikat—consists of a warp and a weft, with the former describing the vertical strands that form the basis, or ground, of an eventual textile and the latter indicating the horizontal strands that are woven in between. Single ikat is a method wherein only one of these two elements is tie-dyed and patterned, further divided into warp ikat and weft ikat, depending on which was resist dyed. Double ikat, on the other hand, indicates that both the warp and the weft were tie-dyed prior to weaving and results in delightfully intricate and delicate patterns.

Ikat in Andhra Pradesh

The earliest visual evidence of ikat in Andhra Pradesh can be found not in surviving textiles, but in the murals that dress temple surfaces. The 16th century Veerabhadra Temple in Lepakshi is famous for such paintings, bearing richly detailed scenes of myth that include depictions of worshippers throughout the ages. Their dress reflects the fashion of the Vijayanagaran period in South India, including several depictions of checked saris that resemble the ikat garments of today. Immediately we can observe in these murals the similarities between the decorative borders of the paintings and the ornamentation of the textiles, both bearing examples of trains of lotuses or diamonds.

While ikat was known and worn in Andhra Pradesh for centuries, it wasn’t actually produced until sometime between the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Before then, locals sported the richly detailed patan patolas imported from Gujarat. These spectacular double ikat garments have enjoyed a well earned fame throughout India and the world for centuries, thanks to their finely crafted grid-based designs and vibrant colors. While the murals of Lepakshi represent a variety of textile traditions, befitting the diverse courtly fashion of the Vijayanagara period, Gujarati patola can be spotted on the figure on the left, as indicated by the geometric floral designs arranged in a grid.

Although there is no precise documentation detailing the emergence of ikat production in this region, it is known that the town of Chirala was the first center for its production and sale. Ikat design in Andhra began humbly with the Telia Rumals; small square cloths with geometric designs rendered in starkly contrasting black, white, and red. With a name meaning ‘oily kerchief’—referencing the treatment of the yarn with oil before dyeing—these little fabrics were used as loin cloths and turbans by fishermen and cowherders. However, their small size and regular shape afforded them a versatility that allowed for countless uses in and around the house, often as a covering of sorts, both decorative and protective. Today, their designs influence expensive saris worn by women around India, with Andhra Pradesh emerging as one of the largest exporters of ikat fabric in the country. Modern centers of production include Pochampalli, Koyalagudam, and Puttapakka, the former of which has achieved particular renown for their very own Pochampalli patolas.

Sharing Sacred Geometry

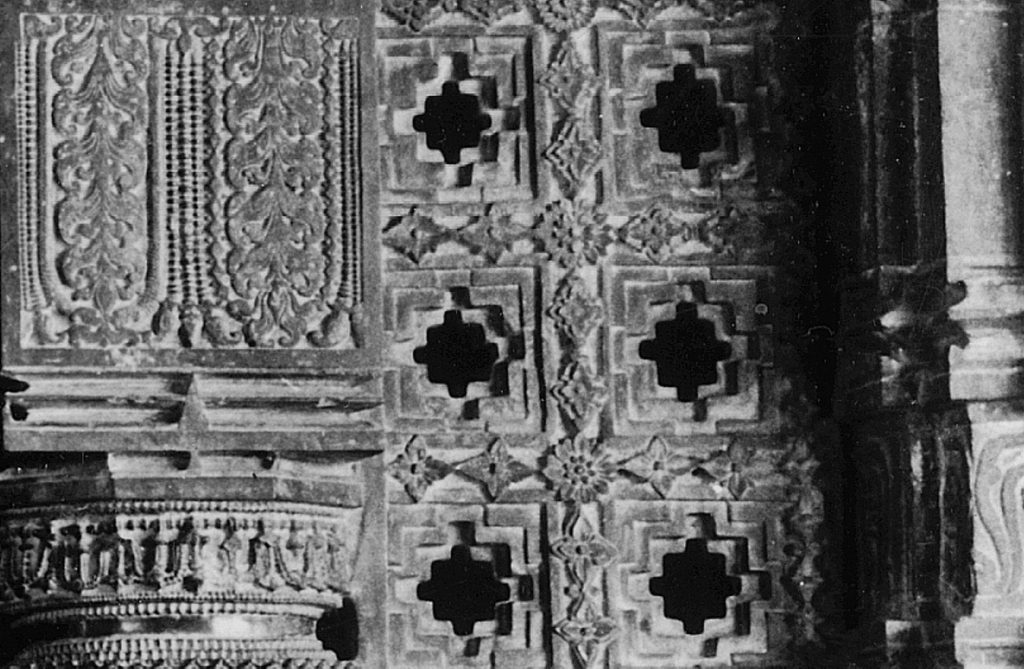

Even the simplest designs are informed by intention and higher meaning. Although the basic patterns of telia can be easily dismissed as incidental ornamentation, to do so is to understate the intelligence of their design and the power of dress in Indian art. The grid, with its mathematical precision and pleasing layout, informs temple design as much as it does the telia. To begin with, it would be easiest to compare what we see in the telia with what we can see in the temple. The straightforward geometries of textile designs are most frequently observed in transitional spaces in temples, including the borders of more complex carvings, as well as the lattice screens that flank entrances to the interior.

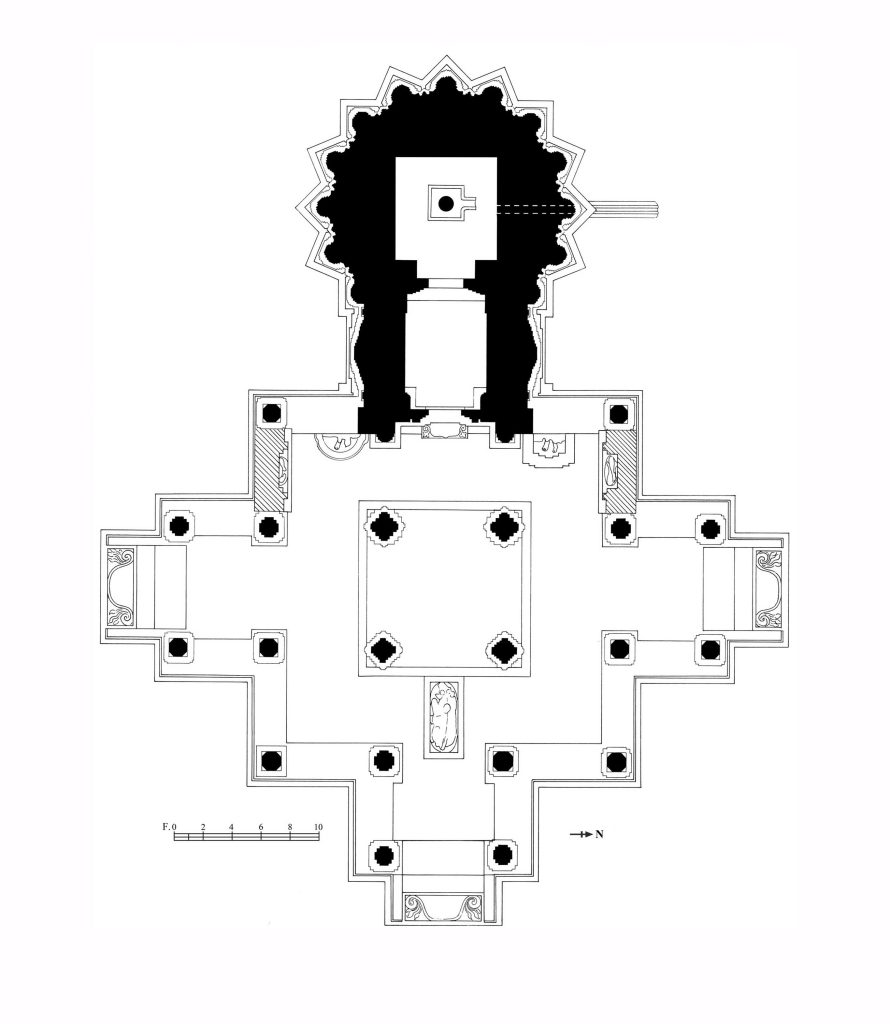

To the left, we can note strong similarities between the temple entrance and the telia saree. The inner patterns are nearly identical, with both repeating the geometric motif known as a sakarnaka, albeit with different layouts—cardinally in the case of the temple tracery (jāla), and diagonally in the textile. Further, the borders resemble each other, with both utilizing what are more or less parallel rectangles.

To the right, an ikat border is compared to the perimeter of a temple doorway. The designs are fundamentally very similar in composition, as both repeat diamonds in a lengthwise sequence. Further, a closer look reveals that both feature diamonds nested within each other. Although the innermost shape is simplified to a dot in the temple, the effect is the same.

The position of these motifs at the entrance to the temple is spatially significant and can inform our understanding of its meaning in the ikat textiles. Placed upon the portal to the divine, these patterns are one method of indicating the transition from the world of the mundane to the sacred. Everything beyond that point is explicitly imbued with a deific significance, as one is made aware they have entered a sacred place. Thus, extending the same symbolism to the act of dressing the body, the ikat garments channel the divinity of these motifs to imbue the flesh with a power and grace much like that found in the aura of temples.

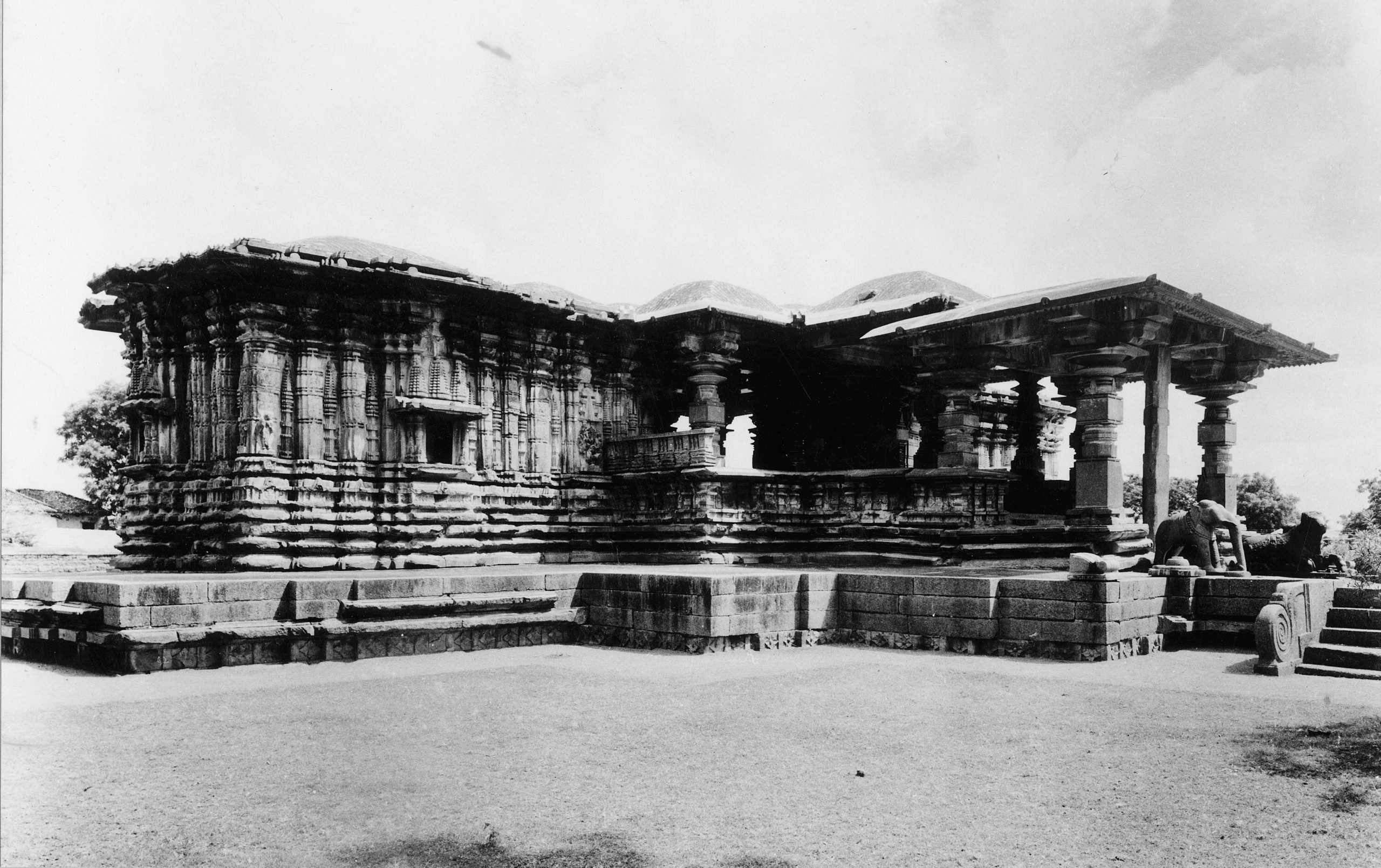

To fully understand the significance of this motif, however, we must take a more abstract view of the temple by examining its layout rather than ornamentation. Although this may seem unintuitive, by paying close attention to the shape of the temple and its boundaries, we are in actuality looking at the shape of sacred space and the forms it takes. To demonstrate this, we will zoom out from the lattice at Hanamkonda pictured above, and consider the plan of the complex as a whole.

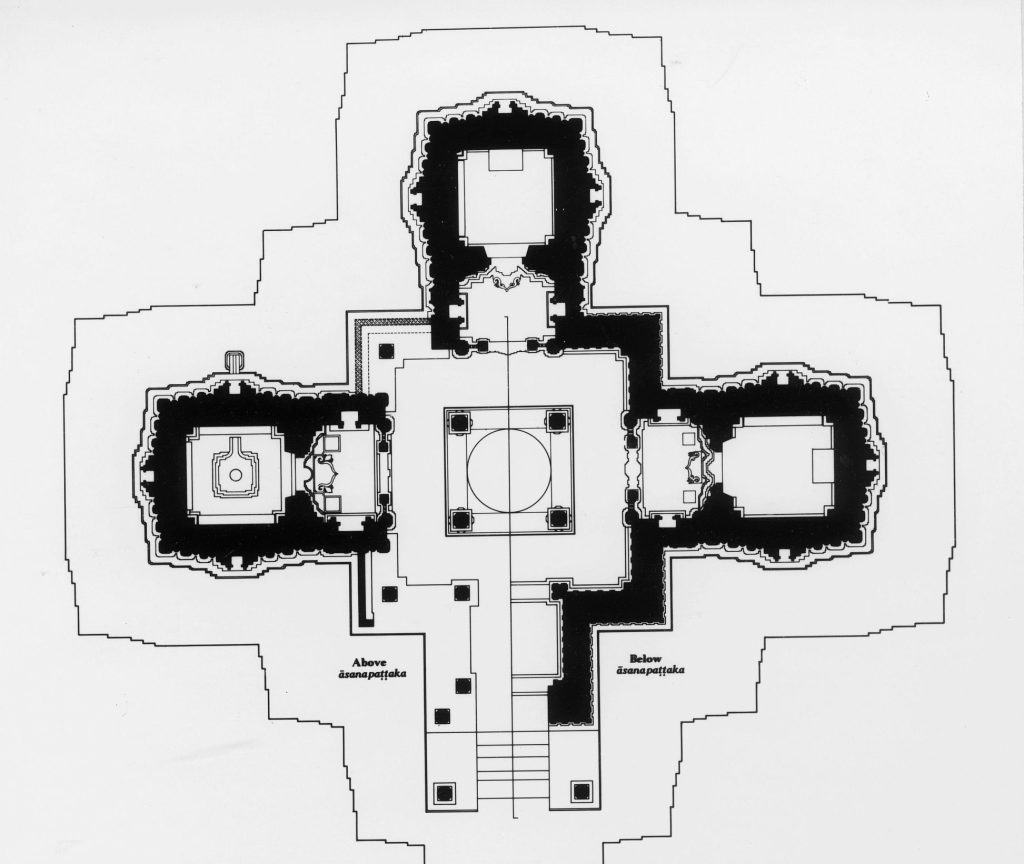

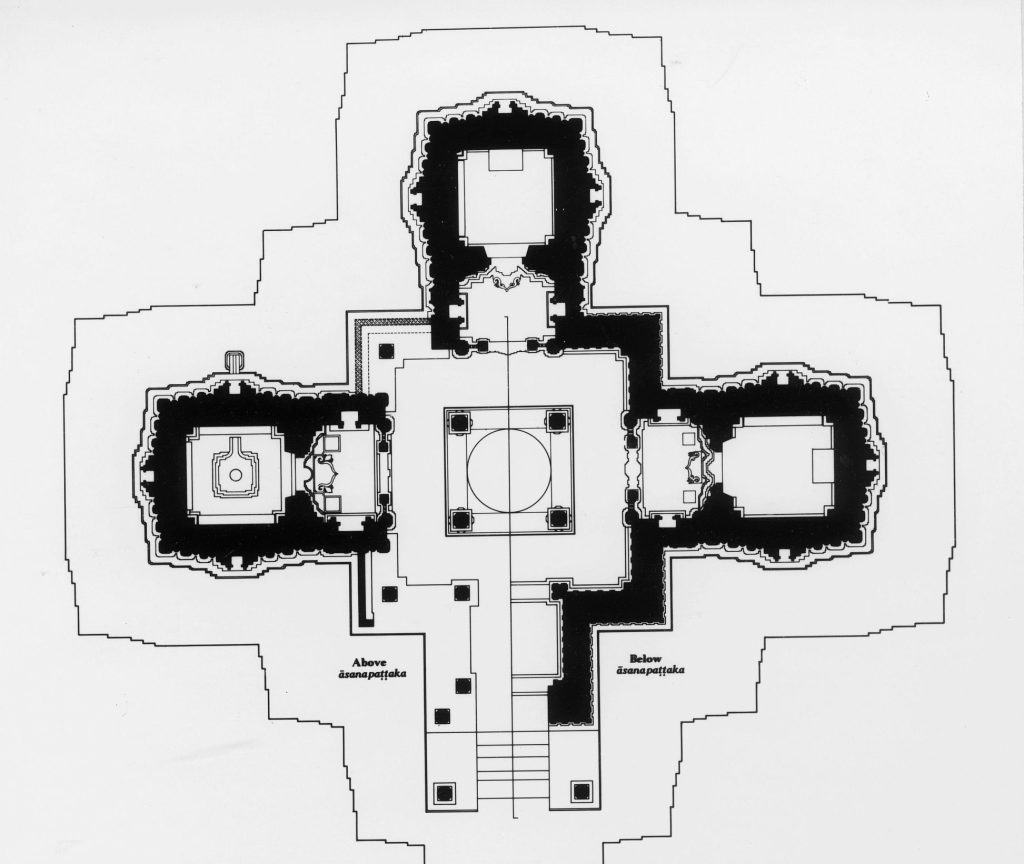

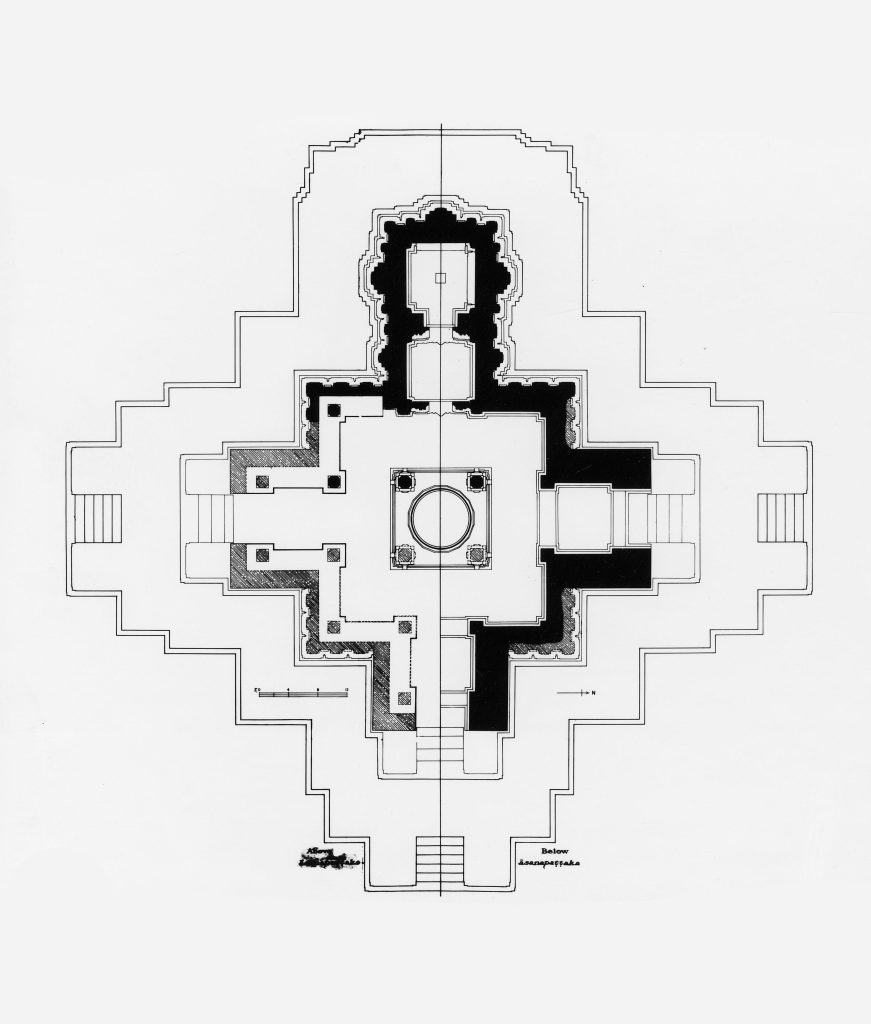

The Thousand Pillar Temple (Veyistambhalagudi) is a trikuta temple, meaning it houses three principal shrines that each contain a murti, or image, for worship. These three shrines are situated around a square mandapa, or pillared hall, from which they protrude to the North, East, and West. In the center of the mandapa is a raised, circular platform that would be used for dancing and other performances. To complete the symmetry of the space, a mukhamandapa, or entry-porch, extends to the South, serving as the singular entrance to the temple. Put together, this produces a shape that is remarkably similar to the sukarnaka jāla that is seen on the entrance to each of the individual shrines.

Thus, the sakarnaka jala is not an incidental pattern, but a method of imparting auspiciousness and power by recapitulating the shape of the temple throughout itself. Quite simply, as temples are sacred places, their form itself is in some ways divine and finds representation in countless aspects of Indian art. As such, the geometric designs of the Telia and similar ikat garments are covered in condensed symbols of sacred space, situating the body within as always being in the presence and protection of the divine. Though the design is simple, the intentionality and meaning behind it is made clear when one realizes that the pattern of the Telia is nearly identical to the layout of the temple, down to the circular form in the center.

It is true, however, that while the sukarnaka is an iconic pattern observed across several mediums, it is also quite simple. How, then, do we know that this is an intentional shape and not incidental ornamentation? To answer this question, we must turn to the philosophy of temple building so as to understand what makes this particular pattern auspicious. When describing the characteristics of a venerable temple in the treatise on the arts, the Visnudharmottara, the sage Markandeya states that “a temple should be made as to have 64 padas [equal parts],” the measurements of which are determined by the relationship between smaller units to the temple as a whole. That is to say, there are strict rules to define the size and shape of temple layouts. Geometric qualities such as symmetry, proportionality, and repetitive form are then important characteristics for the construction of an auspicious temple. With this in mind, it is no surprise that we see many examples of temples with a nearly identical layout and more textiles imitating it.

Further, the celebration of precise, geometric form is not unique to the temple, but instead a fundamental guiding philosophy within Indian aesthetics. Their power and auspiciousness is founded both on their implicit beauty, as well as on their connection with the sacred mandalas and yantras. Though rather esoteric, the essential idea underlying both of these concepts is that they impart some sort of divine grace or power through the intentional arrangement of geometric shapes in predetermined patterns. Through their proportionality, intersections, and form, they acquire a very real power that can be imparted upon their surroundings.

So strong is this belief that it is common practice in South India to create designs outside one’s home using rice flour in a practice called kolam. Every morning at the break of dawn, women clean the entrance to their homes and anoint the ground with auspicious patterns. Coiling loops, sharp edges, and intersecting lines are arranged according to a grid of dots. In doing so, it is thought that one may invite fortune and prosperity into one’s home, attracting the grace of the goddess Lakshmi while inviting harmony with the animals who feed off of the rice. Though in a much more domestic context, this practice shares many qualities with the sukarnaka jalas observed in Hanamkonda and other temples: both imbue thresholds with auspiciousness and power utilizing similar geometric designs.

As both the formal qualities and symbolism of the geometric designs are consistent across their many representations, we can extend this understanding to include their occurrence in textiles with confidence. The geometries, sometimes simple and othertimes not, are a method of imparting divinity and protection to the thing that they adorn. It may be illuminating to consider, however, the spatial relationship as well. If they’re always present on the thresholds to the spaces they protect, how might we apply this to their presence in textiles? Perhaps clothes can be considered as a kind of threshold that lies between the inner self and outer world. Just as stone is dressed with sacred geometry to imbue it with the grace of the divine, so too may flesh be ornamented and transformed into a vessel for the sacred.