The Making of a Pilgrimage: Locations of the Buddha’s Life is a journey through four pivotal sites tied to the life and legacy of the Buddha – Lumbini, where the Buddha was born; Bodhgaya, where he found enlightenment; Sarnath, where he shared his teachings for the first time; and Kushinagar, where his life ended. These sacred sites are more than markers of historical significance; they are living places of transformation, continuously shaped by faith and community. The concluding section, Pilgrimage and Community, explores the enduring tradition of Buddhist pilgrimage, the role of modern monasteries, and community bonds formed through shared experiences, or offering of votive stupas and collecting mementos.

This exhibition is presented through the lens of Professor Frederick Asher (1941–2021), a leading scholar in South Asian art and architecture. Professor Asher devoted much of his career to studying Eastern India, documenting these sites as both sacred and social spaces. His extensive photographic archive, generously gifted to the Center for Art and Archaeology before his passing, captures the profound transformations of these places over decades. Through his images, we glimpse the dynamic histories of these sites – not just as destinations for worship but as living records of change, resilience, and devotion. His unique perspective combines meticulous academic research with a deep appreciation for the spiritual significance of these spaces.

This exhibition invites visitors to reflect on the evolving narratives of these sites and to consider their importance not only in the Buddha’s time but also in the context of modern faith, community, and heritage.

Lumbini: Where Pilgrimage Begins

Lumbini, the place where the Buddha was born, has a rich story that spans thousands of years. It began as a simple garden where Queen Maya Devi gave birth to the Buddha, making the land sacred. Many years later, Emperor Asoka visited Lumbini and, by placing a stone pillar there, confirmed it as an important site while also helping to establish monastic life. Over time, the site was forgotten, but in the 19th century, archaeologists rediscovered it, bringing its history back to life. Today, Lumbini is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, where ancient ruins and modern monasteries come together, and people from around the world visit to experience its deep spiritual significance.

Birth of Buddha

Legend tells that The Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, was born in Lumbini, a serene grove near the foothills of the Himalayas, to Queen Maya Devi, who had a special dream of a white elephant before his birth, symbolizing his greatness. As the story goes, he was born under a sal tree, and as soon as he was born, he took seven steps, with lotus flowers blooming under his feet. He then declared his unique purpose in the world. Celestial beings celebrated his birth with flowers and music, marking it as a moment of great importance. Today, Lumbini is a revered pilgrimage site for Buddhists worldwide.

Secrets from the Sacred Ground

The Maya Devi Temple at Lumbini marks the sacred site where Queen Maya Devi is believed to have given birth to Siddhartha Gautama, who later became the Buddha. The ruins date back to the 3rd century BCE, from the time of Emperor Ashoka, and include remnants of ancient stupas, monasteries, and a sacred pool where Maya Devi is said to have bathed before the birth. The site, with its historical and spiritual significance, was rediscovered by archaeologists in 1895.

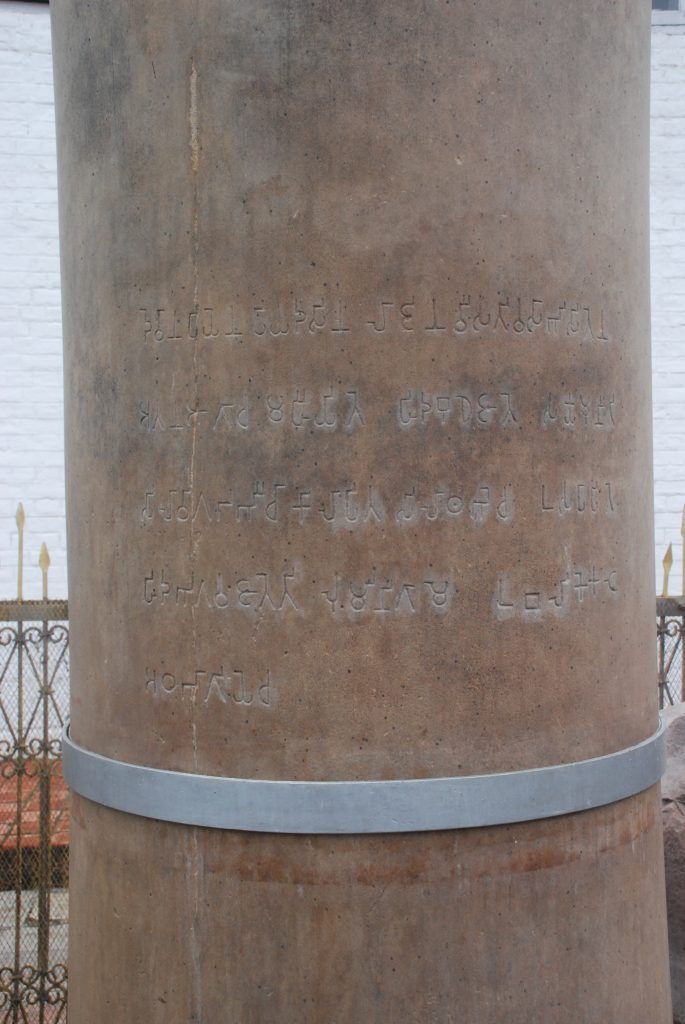

Ashoka's Legacy: A Monumental Link to Buddha's Birth

Ashoka’s Pillar at Lumbini, is a key artifact marking the birthplace of Buddha. The pillar, inscribed with an edict by Emperor Ashoka, was discovered by Dr. Fiihrer in the Nepalese Terai region, north of Gorakhpur. The inscription on the pillar confirms that Ashoka visited the site and erected the pillar to commemorate the Buddha’s birth. It reads: “King Piyadasi [Ashoka], beloved of the gods, having been anointed twenty years, himself came and worshipped, saying, ‘Here Buddha Shakyamuni was born’… and he caused a stone pillar to be erected, which declares, ‘Here the worshipful one was born.'”

The site, referred to as Lummini in the edict, matches the present-day location of Lumbini. The pillar is in its original position and was mentioned by the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang, who visited in 636 CE.

Bodhgaya: Pilgrim’s Awakening

Bodhgaya in Bihar is one of the most significant pilgrimage sites for Buddhists around the world. It is where Prince Siddhartha Gautama attained enlightenment under the Bodhi tree, becoming the Buddha, over 2,500 years ago. The site is marked by the Mahabodhi Temple complex, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which includes the sacred Bodhi tree and an ancient temple with intricate carvings depicting scenes from the Buddha’s life. Bodhgaya attracts visitors for its deep spiritual significance, serene atmosphere, and its role as a key center of Buddhist meditation and learning.

The Mahabodhi Temple: A Journey Through History

The Mahabodhi Temple, the main monument at Bodhgaya, marks the site of the Buddha’s enlightenment under the Bodhi tree, believed to be a descendant of the original tree. A shrine, likely constructed during the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE, initially enclosed the tree. Over the years, the temple underwent multiple renovations, with significant changes occurring during the Kushan period (1st-3rd centuries) and later during the Gupta period (5th-6th centuries). This expansion may have been influenced by Sri Lankan monks who settled at Bodhgaya. Despite being a precursor to the present temple, the original structure was modified in later periods, particularly during the Pala period (9th-11th centuries), when numerous stone sculptures were added. Following the Pala period, Buddhism in India declined, partially due to invasions and the loss of royal patronage, leading to the Mahabodhi temple’s deterioration.

Repairs by a Burmese mission in 1305 sparked debate over whether the temple was entirely rebuilt, though it is more likely that restoration occurred. Today, the temple stands at approximately 48.7 meters high, with a base of 14.6 × 14.3 meters. The large seated Buddha image inside, in the bhumisparsha mudra, dates back to the Pala period. The temple’s preservation is notable, particularly compared to other brick temples in eastern India. The gallery below showcases artifacts and examples from different phases of architecture and art related to the Mahabodhi Temple.

-

- The Mahabodhi Temple, Bodhgaya, Gaya, Bihar, Kushan, Gupta, Modern, 400-525 CE & 1800-1899 CE – Significant restoration, Brick, Frederick M. Asher, FA_00093

-

- Buddha in niche of Mahabodhi Temple, Bodhgaya, Gaya, Bihar, Pala Period, 900-999 CE, Black Stone, Frederick M. Asher, FA_00109

-

- Buddha in the sanctum of Mahabodhi Temple, Bodhgaya, Gaya, Bihar, Pala Period, 800-999 CE, Black Stone, Frederick M. Asher, FA_00111

-

- Lotus Flower, Ratnachakrama (Jewel Walk), Mahabodhi Temple, Bodhgaya, Gaya, Bihar, 600-699 CE, Frederick M. Asher, FA_00153

-

- Buddhapad, Pancha Pandava Annapurna, Mahabodhi Temple Complex, Bodhgaya, Gaya, Bihar, 1800-1899 CE, Basalt, Frederick M. Asher, FA_00134

-

- Lower Portion of a Pillar Shaft, Mahabodhi Temple Complex, Bodhgaya, Gaya, Bihar, c. 268-232 BCE, Sandstone, Frederick M. Asher, FA_00103

-

- Crowned Buddha, Mahabodhi Temple Complex, Bodhgaya, Gaya, Bihar, Pala Period, 800-1099 CE, Stone, Frederick M. Asher, FA_00188

-

- Buddha in bhumiparsha mudra, Mahabodhi Temple Complex, Bodhgaya, Gaya, Bihar, Pala Period, 800-1099 CE?, Stone, Frederick M. Asher, FA_00190

-

- Votive Stupas, Mahabodhi Temple Complex, Bodhgaya, Gaya, Bihar, Pala Period, 800-1099 CE, Frederick M. Asher, FA_00185

The Railing

The main temple, the bodhighara, was enhanced by a stone railing during the Shunga dynasty (185-72 BCE). It is currently displayed in the Bodhgaya Museum as an archaeological artifact for tourists rather than being utilized for worship. This change impacts the way the circumambulation ritual is conducted. In its place, the Archaeological Survey of India has installed concrete replicas of the original railing. This section provides a glimpse of the original Shunga railing now on display at the museum.

-

- Railing Pillar, Shunga Period, 100-1 BCE, Archaeological Museum, Bodhgaya, Gaya, Bihar, Red Sandstone, Frederick M. Asher, FA_00210

-

- Railing Pillar, Shunga Period, 100-1 BCE, Archaeological Museum, Bodhgaya, Gaya, Bihar, Red Sandstone, Frederick M. Asher, FA_00222

-

- Railing Pillar, Shunga Period, 100-1 BCE, Archaeological Museum, Bodhgaya, Gaya, Bihar, Red Sandstone, Frederick M. Asher, FA_00229

-

- Railing Pillar, Shunga Period, 100-1 BCE, Archaeological Museum, Bodhgaya, Gaya, Bihar, Red Sandstone, Frederick M. Asher, FA_00244

The Seat of Enlightenment

The Diamond Throne, known as Vajrasana, is a sacred site where Siddhartha Gautama achieved enlightenment beneath the Bodhi Tree. This ancient stone platform that probably dates to the time of Ashoka (3rd cent BCE), sits on a brick case. The top surface of the slab is decorated with repeated pairs of geese pecking at the base of acanthus. The brick base used to have stucco niches with kneeling pot-bellied figures supporting an entablature. The throne is now covered with a saffron cloth and shielded with a newly made canopy. As a pivotal landmark in Buddhist history, the Diamond Throne continues to inspire pilgrims and visitors alike, serving as a reminder of the transformative power of meditation and the path to enlightenment.

The Seven Weeks of Enlightenment

In the weeks immediately after his enlightenment, the Buddha remained at Bodhgaya. Each week, the Buddha is said to have focused on or achieved significant spiritual insights. The seven weeks are associated with specific events and locations around the Bodhi Tree.

First Week: Attaining Enlightenment under the Bodhi Tree

After his enlightenment, the Buddha meditated for a week under the Bodhi tree at Bodhgaya, where the current pipal tree is considered the fifth incarnation of the original.

Second Week: Gazing at the Bodhi Tree at Animeshalochana Chaitya-Tara Temple

After his week under the Bodhi tree, the Buddha spent another week at Animeshalochana, gazing at the tree for seven days without blinking.

Third Week: Contemplation in a Jewel Walk (Ratnachakrama)

During the third week post-enlightenment, the Buddha walked, causing eighteen flowers to bloom. This is marked by a raised platform with footprints and pillar bases. Pilgrims place flowers on these footprints, like practices at the Vishnupad temple.

Fourth Week: Walking Meditation at Ratnaghar Chaitya

The Buddha’s contemplative event is now associated with the Tara Devi Temple, likely built in the sixth or seventh century. Initially recognized as Tara Devi’s temple by Buchanan-Hamilton, it has a figure misidentified as Tara; the current image is believed to be Bodhisattva Manjushri.

Fifth Week: Under the Ajapala Nigrodha Tree

The Buddha meditated under a banyan tree, where he was tested by Mara’s daughters, representing temptation.

Sixth Week: At the Muchilinda Lake

The sixth week is associated with a lake protected by the Naga king Muchilinda, currently located south of the Mahabodhi Temple.

Seventh Week: At the Rajayatana Tree

The Buddha meditated under the Rajayatana tree during his final week at Bodhgaya, receiving offerings from merchants Tapussa and Bhallika, who became his first followers.

This photo gallery invites you to journey through the monuments linked to the Buddha’s first seven weeks of enlightenment: the Bodhi Tree, Animeshalochana Chaitya, Ratanachakrama, Ratanaghar Chaitya, Ajapala Nigrodha Tree, Muchilinda Lake, and the Rajayatana Tree.

Bodhi Tree

The sacred fig tree under which Siddhartha Gautama attained enlightenment.

Animeshalochana Chaitya

Where the Buddha meditated gazing at the Bodhi Tree without blinking.

Ratnachakrama

Where the Buddha walked eighteen paces back and forth and his steps have been marked by raised lotus stones.

Ratnaghar Chaitya

Where Buddha meditated on the northeast side of the complex near the enclosure.

Ajapala Nigrodha Tree

Nature’s role in the Buddha’s teaching

Muchilinda Lake

Where Buddha meditated, a serpent king protected him from a storm.

Rajayatana Tree

Two merchants, Tapussa and Bhallika, approached the Buddha and offered him honey and rice cakes and became his first lay disciples.

Bodhgaya Sculptures

Bodhgaya is renowned for its stone sculptures. However, there is a 400–year gap in sculptural evidence after the stone railing was constructed around the late second or early first century BCE. This is likely due to the use of perishable

materials, such as stucco, rather than a halt in artistic production. One prominent sculpture from around 383/84 CE is a seated Buddha in red sandstone. Other key works from this period include standing Buddha figures and stucco pieces.

Sculptural activity remained minimal until the Pala dynasty in the 8th century, when Bodhgaya experienced a resurgence in stone sculpture production. Although direct patronage from Pala kings is scarce, the stability of their rule allowed for a flourishing of religious and artistic practices. Inscriptions and pilgrim offerings further highlight Bodhgaya’s importance as a pilgrimage site, with foreign pilgrims’ accounts and Buddhist creed inscriptions enriching its history. Miniature stupas and votive plaques were also common finds. Some Buddhist figures have even been reinterpreted in Hindu contexts, such as a

statue of Avalokiteshvara that was once worshiped as Shiva. These images give a peek into the Pala period sculptures found at Bodhgaya.

Sarnath: Pilgrimage of Dhamma

Sarnath, known as the site of the Buddha’s first sermon, was originally called Mrigadava or Rishipatana. Its identity emerged through oral tradition, and Emperor Ashoka marked it with a lion pillar in the 3rd century BCE, establishing its importance as a pilgrimage site. While initially the name referred to the Dhamek Stupa, it later included a broader archaeological area with monastic remains. Sarnath’s architectural and sculptural evidence highlights its patronage from Ashoka, the Kushans, and the Gupta dynasty, although most artifacts are sculptural. Ashoka’s contributions significantly promoted Buddhism and solidified the site’s relevance. Despite lacking bronze sculptures and a scriptorium, which raises questions about its role, Sarnath’s unique historical and cultural significance leads to discussions about whether it functioned as an unified monastic complex or a collection of distinct monasteries.

The Discovery of Sarnath

The site of Sarnath is identified as the place where Gautama Buddha delivered his first sermon. Sarnath’s history was interrupted after the 12th century, with few Buddhists remaining in India. While other pilgrimage sites like Bodhgaya were visited, Sarnath, was largely neglected. Rediscovered in the late 18th century, British figures like Jonathan Duncan and Alexander Cunningham initiated excavations, with Cunningham focusing on key artifacts like a Buddha image and reliquary. His work, though not always adhering to scientific methods, revealed important sculptures and inscriptions, with local informants aiding his search. Cunningham and his colleague, Markham Kittoe, contributed to significant findings, including statues, a hospital structure, and the Chaukhandi Stupa, though much of the site had been damaged by fire. Later excavations by figures like F.O. Oertel and Sir John Marshall uncovered the famous Ashoka pillar capital, inscriptions, and sculptures, shedding light on the site’s religious and historical significance. Excavations at Sarnath reveal that the oldest levels date to the Maurya period to the reign of Ashoka along with stupas from Gupta and Pala periods. Despite its destruction in the 11th or 12th century, Sarnath remains a key religious and tourist destination, with the Sarnath Archaeological Museum preserving many of its treasures.

The Excavated Site: Unveiling The Layers of a Historic Monastic Centre

Sarnath is a complex archaeological site with a rich history, though its layout and significance may be undervalued by visitors unfamiliar with its role as a lively monastic center. The excavated area covers about 60,000 square meters and primarily consists of building foundations without a clear orientation. The components of Sarnath should be viewed as interconnected rather than isolated, representing layers of construction focused on building rather than function.

The earliest monuments at Sarnath date back to the 3rd century BCE during Emperor Ashoka’s reign, who funded significant structures. Ashoka likely transformed Sarnath from a pilgrimage site into a residential monastery. The Main Shrine, believed to have begun in the fourth or fifth century, coexisted with Ashoka’s pillar, which conveyed edicts to the monastic community. The Ashokan pillar, unearthed in 1904-05, serves as an emblem marking the Buddha’s first sermon, and its message emphasized unity among monks.

The Dharmarajika Stupa, attributed to Ashoka, currently exists only as a circular base. Evidence linking it to Ashoka is tenuous, primarily based on an inscription dating to 1026. The Chaukhandi Stupa, located south of the site, is often dated to the 4th or 5th century and has a Mughal association as well. The Main Shrine or Mulgandhakuti Vihara is a prominent structure believed to be where the Buddha meditated, with its name derived from Xuanzang’s account. The Panchayatana temple, notable for its architectural remnants, lies between the Dharmarajika and Dhamek stupas.

Monastic dwellings at Sarnath lack the systematic arrangement found in other sites, with structures primarily along the periphery. Excavations reveal that these monasteries underwent multiple phases of construction, indicating a rich but complex history. Although many dwellings are identifiable only by their foundations, artifacts like pottery shards suggest the daily lives of monks and nuns, despite ongoing reconstruction obscuring their original forms.

Dhamek Stupa: The Sacred Site of Buddha's Enlightenment

The Dhamek Stupa is a monumental symbol of the Buddha’s teachings, marking the site where he delivered his first sermon after enlightenment. Situated at the easternmost portion of the excavated area, the stupa has a lower section made of stone and an upper part of brick, likely originally faced with stone. Its design includes eight arched projections with niches that once held sculptures of Buddha images, emphasizing its sacred significance. Its impressive architecture and rich history make it a vital pilgrimage site, drawing people from around the world to connect with the enduring legacy of Buddhist teachings.

Sculptural Splendour of Sarnath

At Sarnath, sculptural works were primarily produced in response to major projects like temple construction or stupa restoration. Notably, the polished Ashoka’s Pillar and the capital with four lions, discovered during the 1904-05 excavations, are prominent examples. By the seventh century, when Xuanzang visited, Sarnath likely housed Sammitiya monks, with separate monastic dwellings for different sects, such as Sarvastivadin monks on one side and Sammitiya monks on the other.

Monks were the direct patrons of these sculptures, but merchants and merchant guilds also played a role by providing funding for shrines and stupa expansions. The increased production of sculptures may have been driven by surplus capital from Indian Ocean trade. Excavations have revealed fragments and reliefs that indicate an evolution of early Buddhist art, showcasing influences from earlier periods and local artistic practices. The representation of key events in the Buddha’s life through sculptures illustrates a narrative of pilgrimage and devotion. Royal patronage in the 11th century by figures like Mahipala and Queen Kumaradevi underscores Sarnath’s continued cultural significance, linking it to broader artistic developments in the region.

The gallery showcases major sculptures from Sarnath now preserved at the Archaeological Museum, Sarnath.

-

- Lion Capital, Archaeological Museum, Sarnath, UP, Maryan Period, 299-200 BCE, Chunar Sandstone, 214 cm (H), Frederick M. Asher, FA_00274

-

- Bodhisattva dedicated by Monk Bala in 113 CE, Archaeological Museum, Sarnath, UP, Kushan Period, Red Sandstone, 290 cm (H), Frederick M. Asher, FA_00292

-

- Umbrella originally placed over the head of the Bodhisattva dedicated by Monk Bala, Archaeological Museum, Sarnath, UP, Kushan Period, Red Sandstone, 3 m (dia), Frederick M. Asher, FA_00303

-

- Bodhisattva, Archaeological Museum, Sarnath, UP, Kushan Period, 1-199 CE, Chunar Sandstone, 180 cm (H), Frederick M. Asher, FA_00334

-

- Buddha, Archaeological Museum, Sarnath, UP, Gupta Period, 476-477 CE, Chunar Sandstone, 207 cm (H), Frederick M. Asher, FA_00321

-

- Bodhisattva, Archaeological Museum, Sarnath, UP, Kushan Period, 1-199 CE, Chunar Sandstone, 180 cm (H), Frederick M. Asher, FA_00312

-

- Buddha, Patron: Monk Abhayamitra, Archaeological Museum, Sarnath, UP, Gupta Period, 474 CE, Chunar Sandstone, 120.6 cm (H), Frederick M. Asher, FA_00345

-

- Buddha, Patron: Monk Abhayamitra, Archaeological Museum, Sarnath, UP, Gupta Period, 476-477 CE, Chunar Sandstone, 193 cm (H), Frederick M. Asher, FA_00324

-

- Buddha seated in dharmacakramudra, Archaeological Museum, Sarnath, UP, Gupta Period, 400-499 CE, Chunar Sandstone, 161 x 79 cm, Frederick M. Asher FA_00338

-

- Buddha in abhayamudra, Archaeological Museum, Sarnath, UP, Gupta Period, 400-499 CE, Chunar Sandstone, 178 x 44 cm, Frederick M. Asher, FA_00328

-

- Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, Archaeological Museum, Sarnath, UP, 600-799 CE, Chunar Sandstone, 83 x 124 cm, Frederick M. Asher, FA_00380

-

- Buddha’s First Sermon, Archaeological Museum, Sarnath, UP, 800-899 CE, Chunar Sandstone, 118 x 78 cm, Frederick M. Asher, FA_00423

Kushinagar: Final Steps of the Pilgrimage

Kushinagar, the capital of the Mallas, is one of Buddhism’s most sacred sites, where the Buddha attained Parinirvana. After a period of decline, Kushinagar flourished again during the Maurya and Gupta periods, marked by the construction of numerous stupas and monasteries. Chinese pilgrims Fa-Hien, Xuanzang, and I-Tsing documented the site’s grandeur in the 5th to 8th centuries. Excavations led by archaeologist A.C.L. Carlleyle in 1876 and the Archaeological Survey of India between 1904–1912 uncovered key structures like the main stupa, Nirvana temple, and monasteries, along with artifacts such as clay seals, coins, and terracotta figurines, reflecting its rich history from the Mauryan to the 10th century CE.

Parinirvana Stupa and Temple

The Parinirvana Stupa in Kushinagar is the site believed to be where Gautama Buddha attained Parinirvana, or final liberation, in 487 BCE. To honour this sacred place, Maurya King Ashoka built stupas here around 260 BCE, and the site was further expanded during the Kushan and Gupta empires. In 1876–77, Carlleyle uncovered the remains of the Mahanirvana Stupa and a 6.1 meter statue of the reclining Buddha. Carved from a single sandstone block, the statue shows Buddha lying on his right side, symbolizing the sunset of his life, with his right hand under his head as a cushion. An inscription identifies it as a religious gift from a devotee named Haribal, and today, the statue is enshrined in the Mahanirvana Temple, situated next to the stupa.

Further excavations in 1910 revealed artifacts, including coins from rulers Jai Gupta and Kumar Gupta. In 1956, marking the 2500th Buddha Jayanti, the temple and stupa were restored to their present form. The main stupa, with its circular base and dome, stands 19.81 meters tall and remains a central point of devotion in Buddhist heritage.

Rambhar Stupa: The Sacred Site of Buddha's Cremation

Rambhar Stupa is considered the site of the Buddha’s cremation. Buddhist texts refer to it as Makutabandhana Chaitya, an important spot marking the end of the Buddha’s earthly journey. Excavations in 1910 and 1956 revealed a massive circular drum, measuring 34.14 meters in diameter, resting on a circular plinth with multiple terraces. Around the main stupa, smaller structures and votive stupas are also found. Artifacts like clay seals and decorative bricks were also discovered, highlighting the site’s historical and spiritual significance.

Matha Kuar Shrine

The Matha Kuar Shrine in Kushinagar, located about 400 yards from the Parinirvana Stupa, features a 3.05 meter–tall Buddha statue carved from blue stone from Gaya, Bihar. Depicting the Buddha in the bhumisparsha mudra, it symbolizes the moment before his Enlightenment. The statue, believed to date to the 10th or 11th century, is thought to mark the site of the Buddha’s last sermon. Discovered by Carlleyle in 1876 and restored after being broken, it was installed in the temple in 1927.

Pilgrimage and Community: A Shared Journey

Votive stupas are small structure offerings made by individuals or communities. While their exact purpose remains uncertain due to the absence of inscriptions, they probably served as symbols of devotion and connection to the sacred. Pilgrims dedicated these miniature stupas after visiting key sites in the Buddha’s life, or on behalf of those unable to make the pilgrimage themselves. The examples from Bodhgaya and Sarnath were likely offered to connect with Buddha’s lineage.

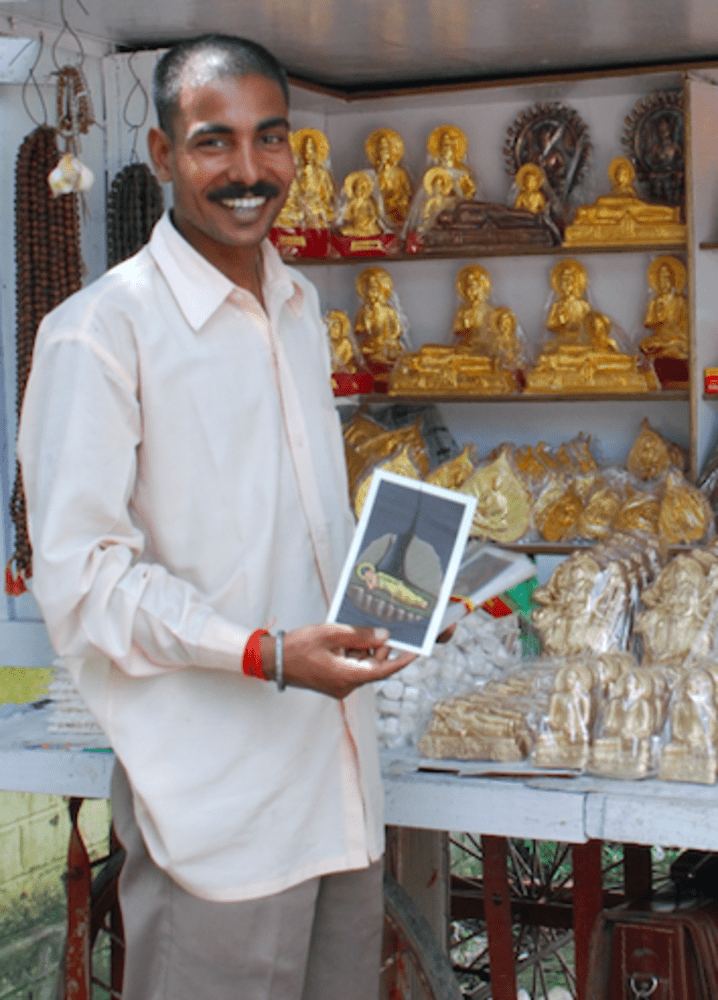

Souvenirs of sacred sites and Buddha, sold at these pilgrimage sites, have become a common way for devotees and tourists to take home a piece of spiritual connection.

The commercialization of these items, while providing local artisans with livelihood opportunities, also reflects the blending of spirituality with consumerism. The merging of Buddhist iconography with pop culture reveals the widespread cultural appropriation of sacred imagery. Despite this, these items serve as reminders of the enduring global significance of these sacred sites.

Bodhgaya, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is the most enduring pilgrimage site connected to the Buddha’s life, attracting international visitors and housing monasteries from countries like China, Myanmar, Sri Lanka etc. In Lumbini too, international monasteries represent diverse Buddhist traditions and architectural styles, creating a vibrant community that offers meditation retreats, monastic spaces, and cultural events. These monasteries contribute to the area’s active role in fostering spiritual practice and cultural exchange. Similarly, Sarnath, the site of the Buddha’s first sermon, experienced a revival in the 19th century, leading to the establishment of monasteries by Buddhists from Burma, Japan, and other nations. Anagarika Dharmapala, a Sri Lankan monk, played a key role in revitalizing Sarnath by founding the Maha Bodhi Society and constructing the Mulagandhakuti Vihara in 1931. Together, these monasteries across Bodhgaya, Lumbini, and Sarnath serve as living centers of Buddhist heritage and international dialogue.

Further Reading

Asher, Frederick M. Bodhgaya: The Site of the Buddha’s Enlightenment. Oxford University Press, 2008. New Delhi.

Asher, Frederick M. Sarnath: A Critical History of the Place Where Buddhism Began. Getty Publications, 2020. India.

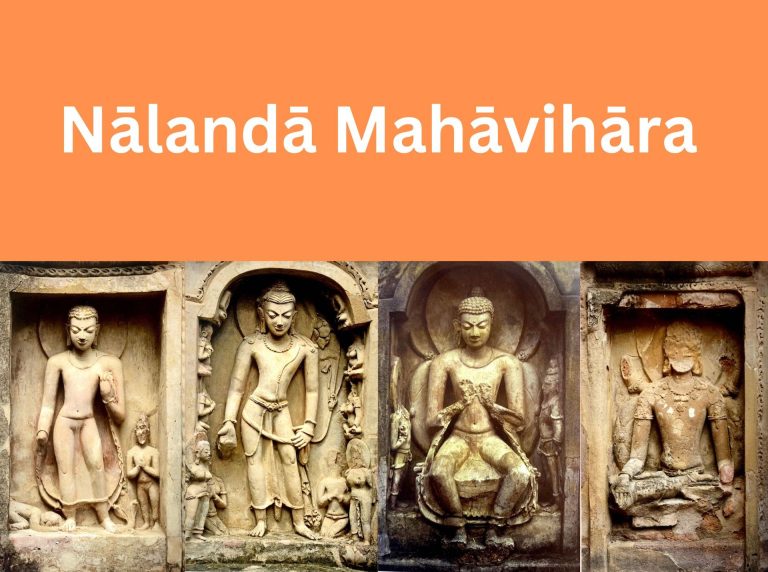

Exhibition ‘Situating the Great Monastery of Nalanda Through the Asher Archive‘ by Jamphel Shonu, Digital India Learning (DIL) 2023 Fellow

This exhibition has beed curated and designed by Stuti Gandhi, Senior Research Associate at the Center for Art & Archaeology, American Institute of Indian Studies.