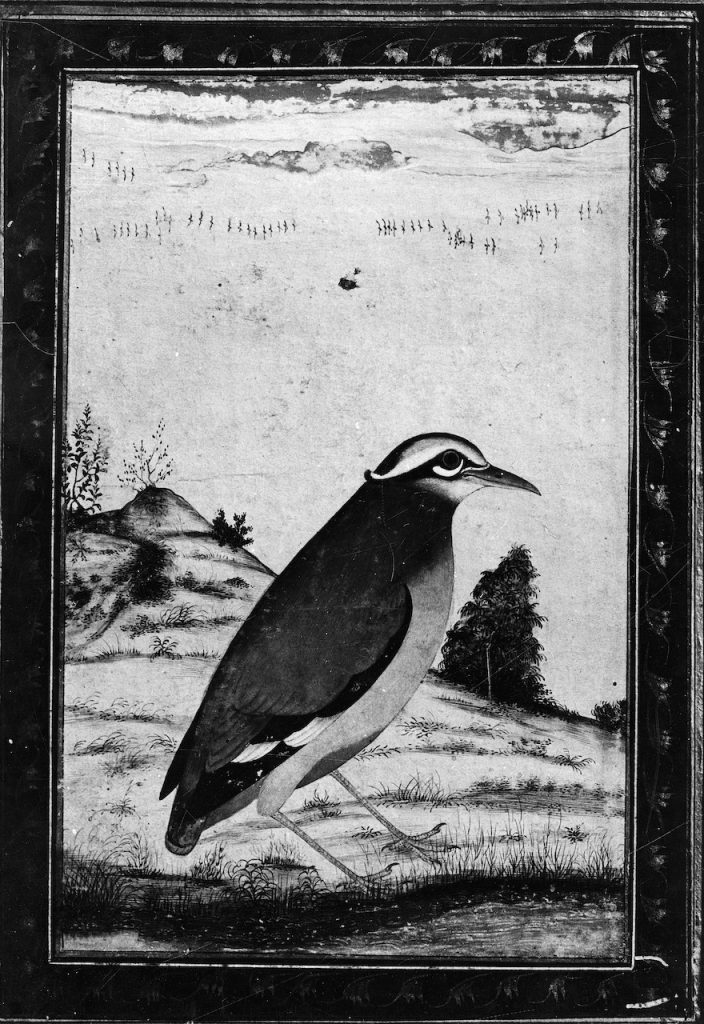

White-breasted kingfisher, around 1625, 6.5 x 6 inches, Sir Cowasji Jehangir Collection. Karl Khandalavala and Moti Chandra, Miniatures and Sculptures from the Collections of the Late Sir Cowasji Jahangir, Bart (Mumbai: Board of Trustees of the Prince of Wales Museum, 1965), 29.

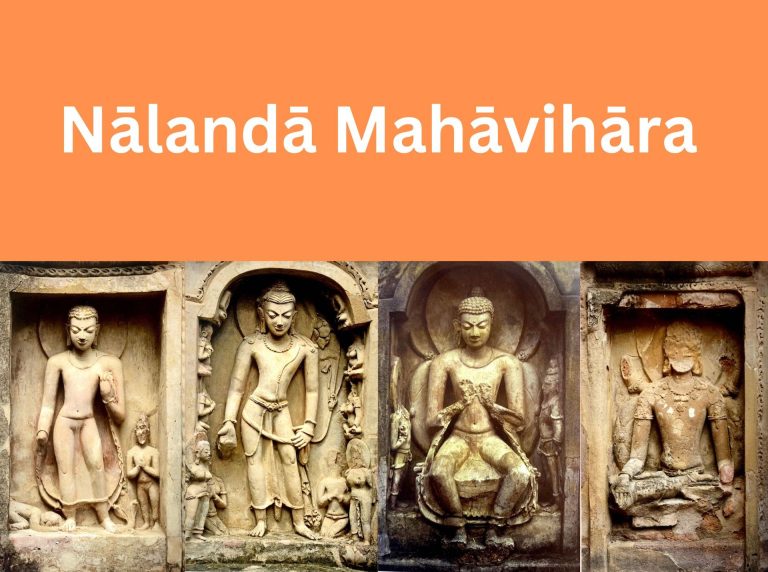

A digital exhibition curated from the the Center for Art and Archaeology's photo archive of Jahangiri folios. The project is a culmination of the Digital India Learning Student Fellowship awarded to Ankush Arora, Graduate Student, Syracuse University.

Jahangir (b. 1569, r. 1605-27), the fourth Mughal emperor in the Indian subcontinent, was known for his deep fascination for the natural world, which he carefully described in his autobiography, The Jahangirnama. Different species of flowers, plants, mammals, and birds attracted his attention, and he ordered his artists to paint their portraits in the most realistic manner possible. Jahangir inherited his passion for the natural world from Babur, the Mughal empire’s founder, and his own father, Akbar, whose biographies contain vivid descriptions and illustrations of plants, animals, and birds. Paintings from the reigns of Jahangir’s predecessors heralded a new chapter in Indian art as artists received royal patronage to portray wildlife and natural phenomenon. But it was during Jahangir’s period that the genre of natural history paintings takes shape because of the artists’ emphasis on portraying plants, animals, and birds with great accuracy, and individual characteristics.

This exhibition brings together a collection of early seventeenth-century paintings from Jahangir’s period, which reflect his abiding interest in the nonhuman, and his keen observation of their physical features and behaviour. Divided into three parts, the exhibition presents ten portraits of birds, mammals, plants, and flowers. These portraits relate to anecdotes in Jahangirnama, in which the emperor enthusiastically writes about the beauty and strangeness of animals that he received as rare gifts, including a falcon from Persia, and a zebra from Ethiopia. The portraits reflect the Mughals’ attempt to understand the natural world through the emperor’s scientific observation and through the artists’ paintbrush.

Documented specimens of painted folios belong to the collections of the National Museum, Delhi; Sir Cowasji Jehangir Collection, Mumbai; Salar Jung Museum, Hyderabad; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Exhibition showcases rare works of folios that have not been published

Center for Art and Archaeology's Photo Archive of Jahangir Folios

Some of these portraits were executed by major painters of the royal court, such as Ustad Mansur and Manohar, among the most famous Mughal artists of flora and fauna

Collection opens up research avenues to identify artists, styles and techniques, authenticity of works, years of production, issues of provenances and species of animals and plants

Mughal Emperor Jahangir and the Nonhuman

What emerges from the exhibition is a representation of nature as seen by human beings. The first is the emperor Jahangir, who observed and collected the animals and birds as his prized possessions. The second were the artists who drew their portraits, and accommodated his ideas while creatively working on the king’s perceptions about the natural world.

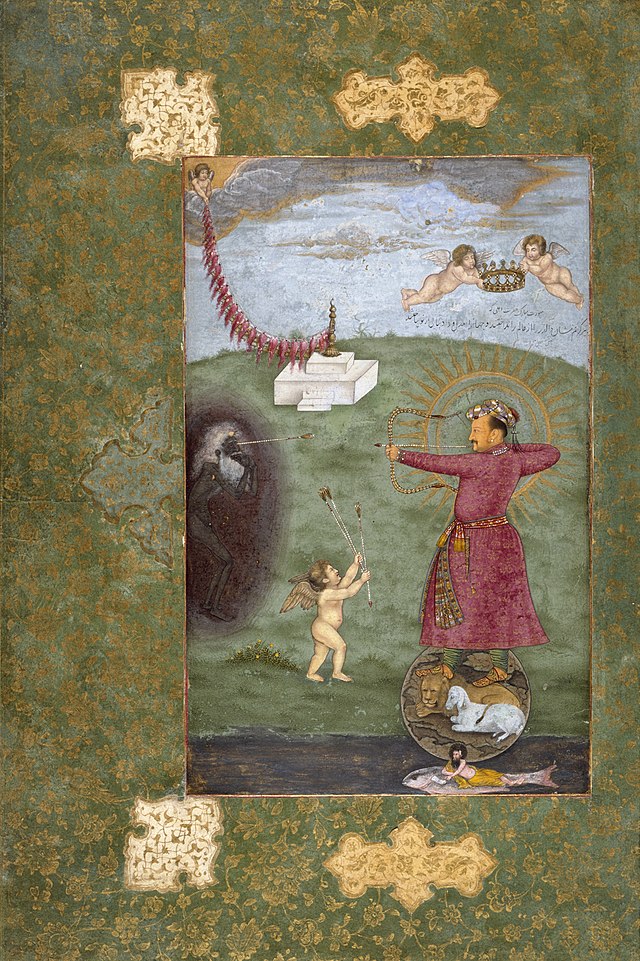

A powerful example of the emperor’s command over the nonhumans is the image of him standing atop a globe, with the animal kingdom living under his feet. The emperor is presented as the ruler of a just and orderly universe, which includes animals, both domesticated and wild, living together in harmony.

How do we view this image and the other portraits in our era of unprecedented extinction of animal, plant, and other nonhuman species because of excessive human activity? Viewed at a time of the climate crisis, the exhibition asks questions and issues about the impact of the human beings’ enormous extraction of natural resources on the survival of the world’s biodiversity. Some of the endangered species include the lesser flamingo bird and the mouflon sheep, whose portraits are part of the exhibition.

Can we re-imagine nature without human alteration, such as the erosion of forests, and the hunting of wild animals? Can we also re-think the relationship between humans and nonhumans, which is more equitable? The exhibition ponders over these questions, with the intention of looking afresh at the Jahangiri folios from the perspective of environmental balance, and preserving human-nonhuman inter-relational aesthetics and associations.

Jahangir’s abiding preoccupation with the natural world situates his work within the realm of the nonhuman, a term that has gained currency as a subject of research since the late twentieth century. The nonhuman can be defined in terms of animals, organic and geophysical systems, affectivity, bodies, materiality, and technologies. Three reasons demand attention toward the nonhuman. The first is the need to challenge human exceptionalism in the age of the Anthropocene, the current era of climate change where human beings have played the dominant role in significantly altering the environment. The second is that most twenty-first century problems, such as climate change, drought, and famine, involve an engagement with the nonhuman. Thirdly, there is a growing recognition that nonhumans function independently of “human will, belief, and desires,” and are seen as sentient beings, with agency and subjectivity. The project draws upon these ideas, and the analysis of each of the ten objects, in some way or the other, alludes to the “nonhuman turn” by focusing on the moods, feelings, and materiality of the plants and animals, and their relationship with humans.

Read more: Grusin, Richard, ed. The Nonhuman Turn. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Birds

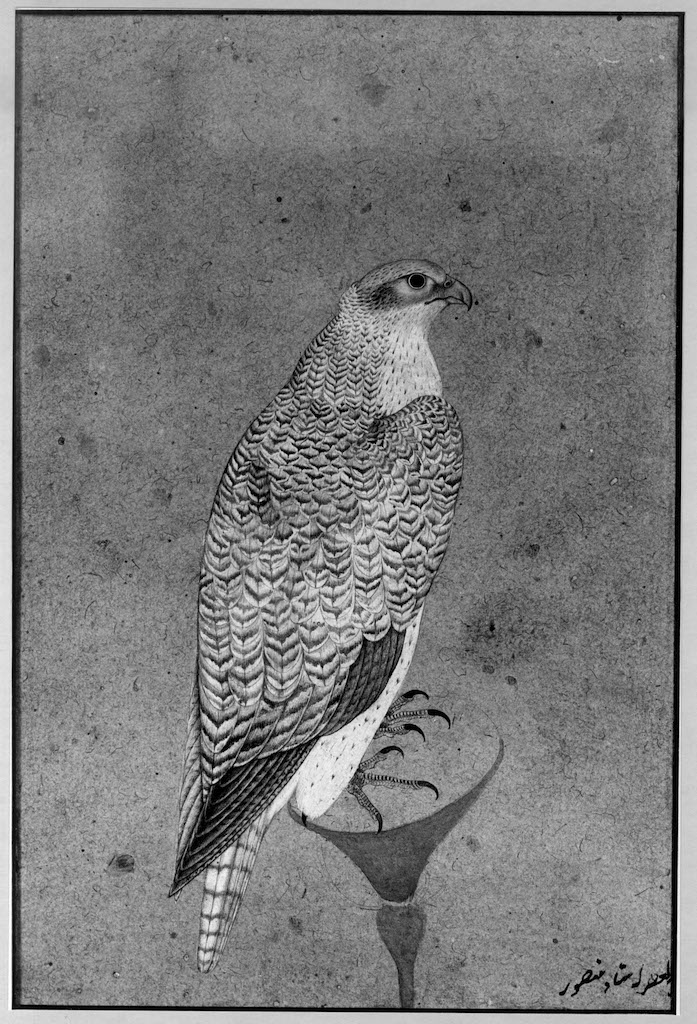

Falconry, the ancient sport of training falcons, hawks, and other birds to hunt animals, was the Mughals’ favourite distraction. Jahangir was also fond of hunting birds, such as falcons and hawks, an interest that he frequently writes about in his memoir. The falcon, often presented as a gift to the Mughal king, was a popular subject of folios during the Jahangir period.

A few of them have been attributed to the royal artist Ustad Mansur, including a folio from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The work relates to Jahangir’s description of the falcon, which he received from the Iranian emperor Shah Abbas in the early seventeenth century. Although the falcon had survived a vicious attack by a cat, it did not prevent Jahangir from noticing its physical beauty, as described below in the emperor’s words.

“What can I write of the beauty of this bird’s colour? It had black markings, and every feather on its wings, back, and sides was beautiful. Since it was rather unusual, I ordered Master Mansur the painter, who has been entitled Nadirul’asr [Rarity of the Age], to draw its likeness to be kept.”

True to Jahangir’s description, the falcon’s feathers have been painted with fine detailing and realism, which is a characteristic style of Mansur’s paintings of animals and birds. The bird’s piercing eye and a razor-sharp beak transform one of Jahangir’s favourite birds into a regal presence. The falcon has been identified as gyrfalcon, a species of falcon that is one of the fastest animals on earth. The image corresponds to its status as an important bird because it was part of the emperor’s hunting expeditions. The falcon received special attention at the Mughal court because it was mostly accompanied by its caretaker, the falconer, who was responsible for training the bird.

The inscription, at the bottom right of the work’s corner, reads in Persian: “Work of Nadir u’l ‘Asr Ustad Mansur.” The Devanagari script, seen at the bottom-left of the work in the MFA collection, remains undeciphered and requires translation.

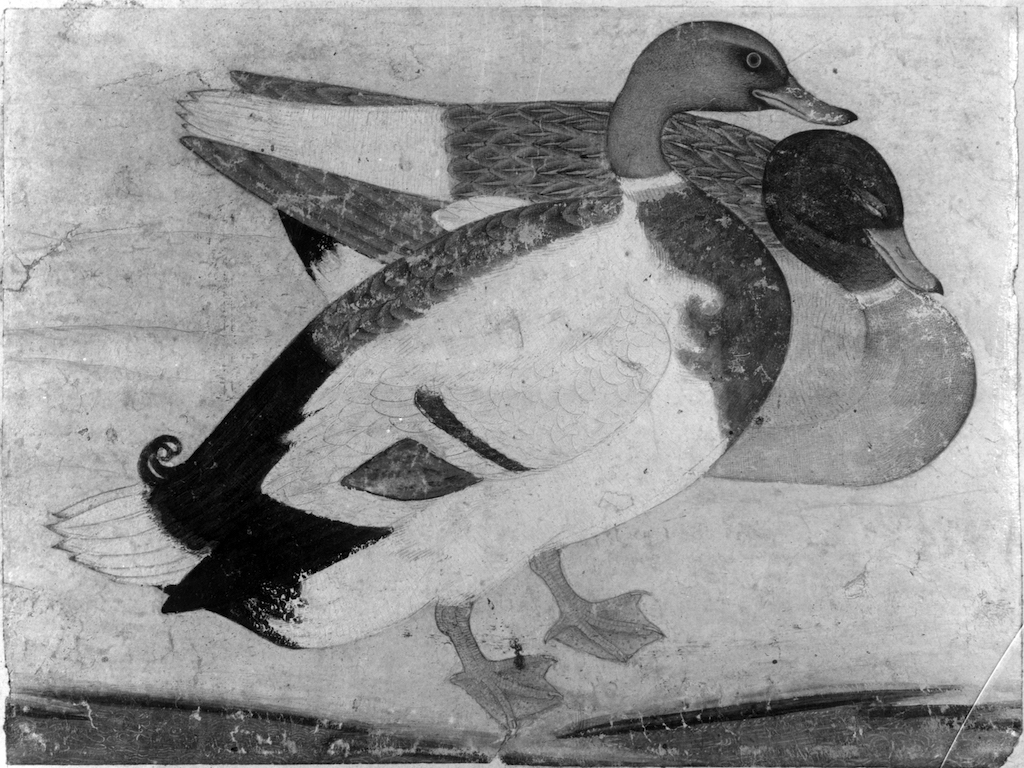

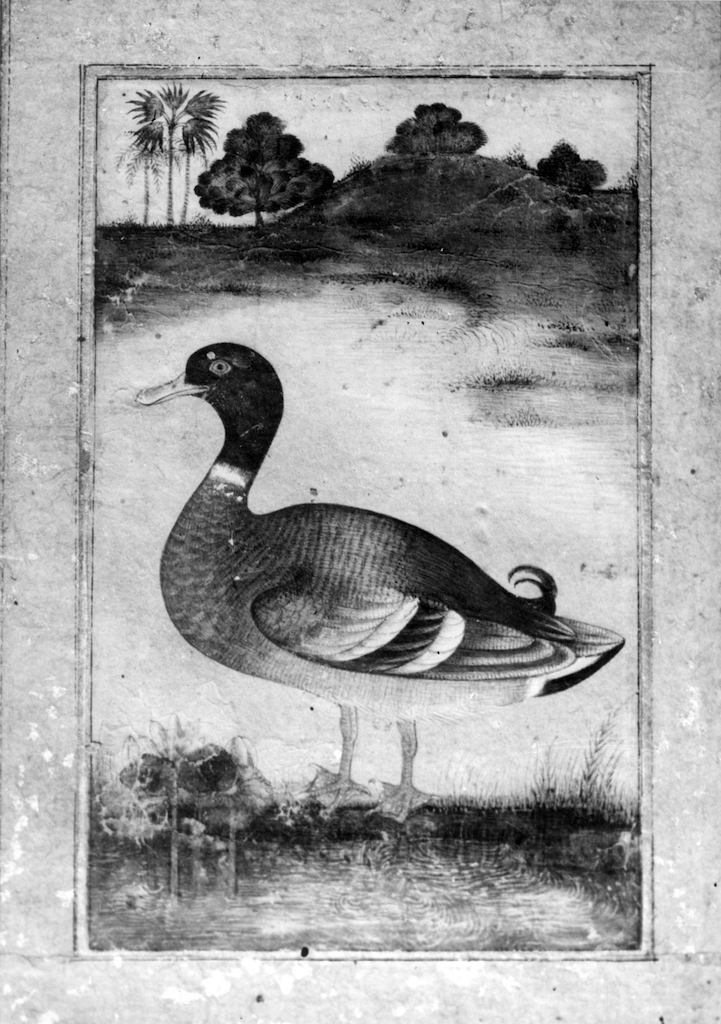

Jahangir's words from Kashmir: At every spring, a duck puts its beak to drink — like golden scissors cutting silk

Based on the account in Jahangirnama, the duck was a frequently hunted bird, especially during the emperor’s four-month stay in Ajmer, when one thousand two hundred ducks were hunted. The documented folios from the CA&A collection belong to the 1620s, when Jahangir visited Kashmir. During his visit, the emperor carefully recorded details of the land’s topography, its agricultural largesse, fruits, animals, and birds, such as chickens and ducks. He spotted the duck during his travels in Kashmir, and described its presence, in a garden, in poetic language.

The foliage in the two paintings suggests the proximity of the ducks near their habitat of a water body, recalling Jehangir’s descriptions of the ducks in the lakes of Kashmir. The line drawing in the Museum of Fine Arts’ work, also attributed to Ustad Mansur, resembles the fine detailing of the feathers of the falcon, executed by the same artist. The brownish neck of the duck, which is in the front, indicates that it is a female mallard, but its curved feathers are characteristic of its male counterpart. The other duck’s green neck is also characteristic of a male mallard, as these pictures show. The work shows a likeness to the real bird as the artist has paid attention to the duck’s colours of maroon-brown, blue, green, and white. It looks like the artist has combined male and female characteristics in the same bird.

The duck’s prevalence in Indian topography also speaks to the bird’s presence in Indian art, such as the wall paintings of Ajanta caves in Maharashtra, the murals dating from the sixth to the eighth centuries. Other references include the work of well-known artists Abanindranath Tagore and Ramkinkar Baij. Tagore initiated the Bengal School of Art that contributed artistically to the Indian National Movement in the twentieth century. Baij was a modernist, who spent his creative life in the university town of Santiniketan, near present-day Kolkata, India.

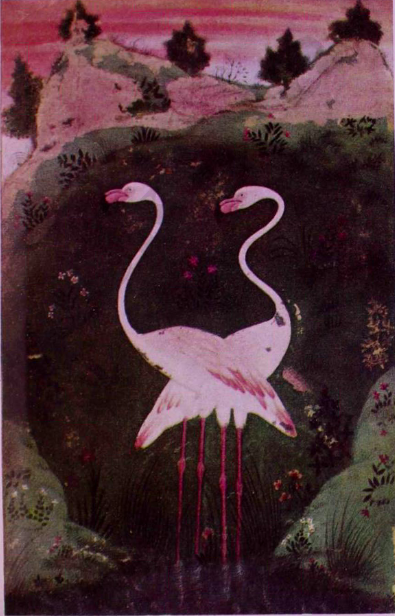

Jahangirnama does not mention a pair of flamingoes in a pool, but the folio’s landscape evokes a similar topography of hills and vegetation seen in the portrait of a single mallard wild duck. Both the works were executed around the same time in the 1620s, and belong to Sir Cowasji Jehangir Collection, which is named after the well-known patron of Indian art (1879-1962).

The bird’s species is the endangered lesser flamingo, which is found in parts of western India (Gujarat and Rajasthan), apart from Pakistan, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, West Africa, and Southern Africa.

The artist has paid attention to the bird’s pink-maroon bill and legs, spotted feathers, and sharp eyes, which suggest that the work is an authentic study of the flamingo.

A lyricism characterizes this work because of the way the flamingos have balanced their bodies on slender legs, and the way their swirling necks indicate movement. The artist has used a similar combination of pink and maroon to highlight the sky, and its possible reflection over the hills below, creating an ambience of sunset.

Jahangir makes no mention of the white-breasted kingfisher in his biography, but the bird is found in parts of South Asia, including India, and it is also found in Israel, Iraq, Egypt, Europe, Thailand, and Sumatra. As Jahangirnama does not include a reference to the bird, it is difficult to guess whether the bird in the Coswaji collection was sighted in India or gifted to Jahangir from foreign dignitaries visiting the Mughal court.

Yet, an observation by Karl Khandalavala and Moti Chandra that the work’s deep yellow background signifies the “intensity of Indian sunlight” suggests that the bird captured in this image may have been sighted locally. At the bottom of the work, sunflowers and a thin patch of grass indicate the kingfisher’s presence in its natural surroundings, perhaps in its own habitats of forests, ponds, gardens, fields, mangroves, beaches, or swamps. Right above the deep yellow are a few strips of pale blue and orange, recalling the dramatic blending of colours during sunset. The artist has minutely depicted a flock of birds by creating short and vertical markings at the top of the work. The birds flying over the sky, like a string of thread, are also seen in the Indian pitta’s portrait in this exhibition.

The kingfisher’s green feathers, with spots of blue, a maroon-brown body, and an elongated bill show that the artist has depicted the subject with great resemblance to the real bird. The work stands out among the flora and fauna studies from the Jahangir period because of a bright colour palette, and a simple but prominent border on all sides of the painting.

This portrait of a bird shows an Indian pitta, which is found in most parts of the country, and in other countries of South Asia, such as Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Bhutan. The bird is also referred to as Navrang, or nine colors, because of its green shoulder, blue feathers, a brown crown, a bright red vent (underparts), and pink feet. When compared with the Indian pitta’s photographs, the portrait, belonging to the Cowasji Collection, is a realistic portrayal of the bird.

Although a coloured photograph of the pitta’s study is not available, the varying contrasts highlight the bird’s colours on the crown, the feathers, the shoulders, and the vent. In the work, the landscape of trees, plants, and wild vegetation also gives an idea about the bird’s habitat, which is a forest where shrubs, herbs, seedlings, and saplings typically grow, and appear to do so without human agency.

In the works discussed here, birds stand out in the natural landscape or against a neutral background, with no or little human presence. These folios leave us with the impression that the sole objective was the nonhuman creatures, who have been painted as portraits of a kind, and as intense studies. When carefully scrutinized, perhaps with a magnifying glass, the portraits reveal emotional content which is infused in their body stance, along with physiological details, much like the human portraits in Mughal painting. The concluding section of the exhibition dwells upon the subjectivity of birds, and reimagines them as creatures of their lands, imbued with a vibrancy of colour and body movement, and gifted with unique sounds.

Indian, Persian, European Influences on Mughal Painting

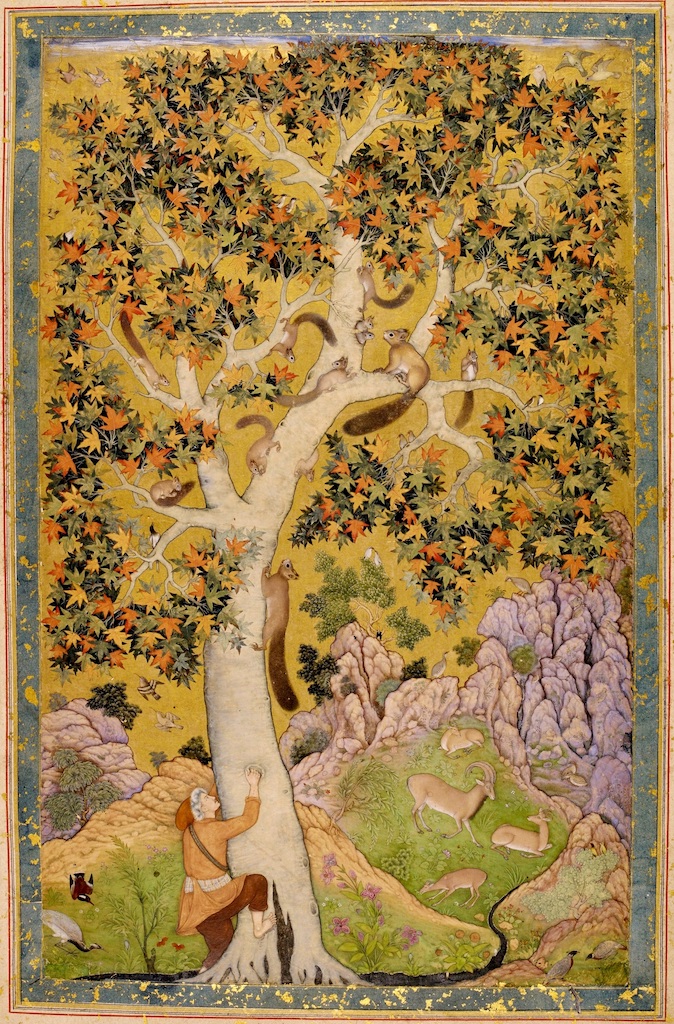

A multitude of styles contributed to the vocabulary of the portraits of animals, birds, and plants during the Mughal period. The illustrations in Baburnama and Akbarnama show that the Mughal artists portrayed wildlife with realism, with a sense of movement and individuality. This realistic style departed from the Persian influence of depicting nonhumans as less natural and more mythical. The European technique of the shading and modelling of figures contributed to the naturalistic quality of these paintings, a style that peaked during Jahangir’s period.

An acute emphasis on the physical features of the subjects, including scientific accuracy of their anatomical parts and their myriad colours, characterized the content of Jahangiri paintings. The influence of European botanical illustrations and engravings of plants and animals have also been noted in these paintings.

Many of these portraits hint at the mood of animals and birds, giving a unique psychological stance to these subjects. This emotionalizing of the nonhumans recalls the ancient Indian tradition of treating the natural world with reverence and empathy.

The Art of the Book: Mughal Manuscript Painting

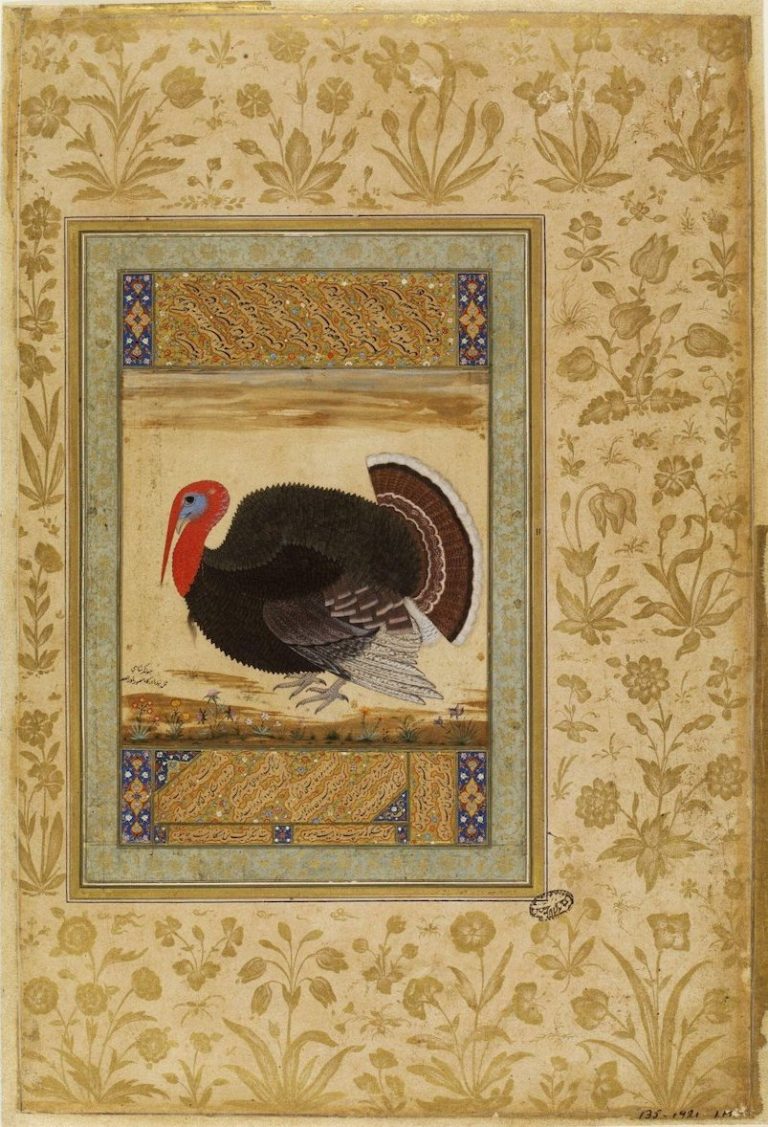

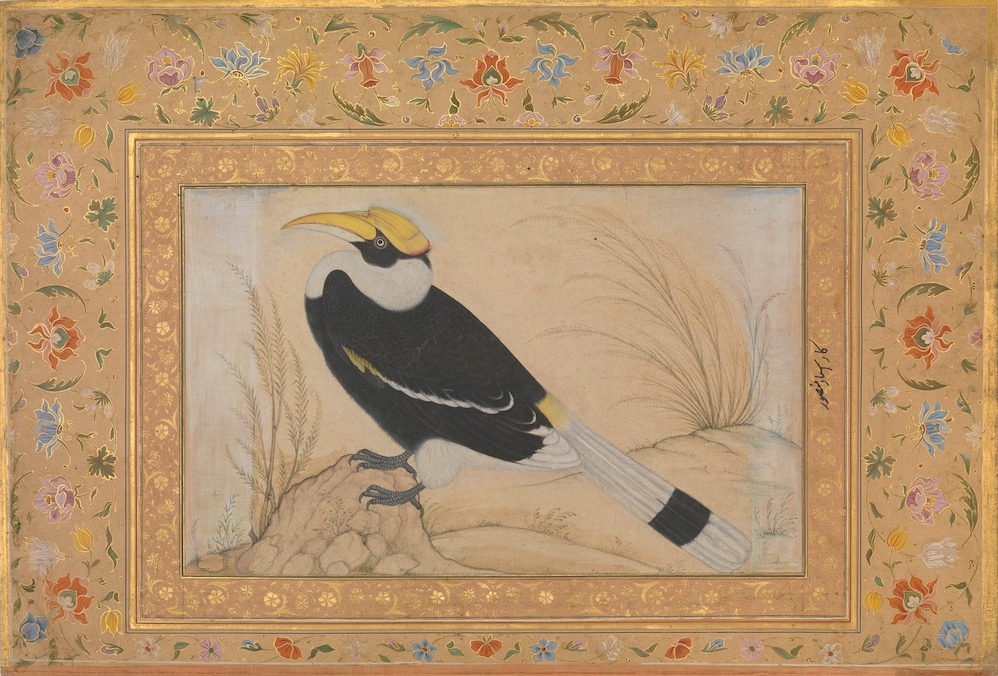

Great Hornbill, Mansur, Folio from the Shah Jahan Album, recto: around 1540; verso: around 1615–20, Purchase, Rogers Fund and The Kevorkian Foundation Gift, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1955, 55.121.10.1

The painted folios are individual pages with a miniature painting because of their small format. The medium of the Mughal painted images was watercolour, and artists largely used the gouache technique. These paintings were bound as royal albums, and the art of binding an album or muraqqa demanded experts in the technique, an art form that was greatly appreciated in the cultural milieu. Mostly, an ornamental border of calligraphic inscriptions, and/or flora and fauna surrounded the pictures, and the reverse of the folio often displayed calligraphy.

The animal and bird studies of Jahangir’s period were added in the muraqqas of later period, and we see these portraits in albums attributed to the emperor Shah Jahan’s patronage. The albums belong to the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City; the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin; and Victoria and Albert Museum, London, among other institutions.

Mammals

Elephant - Jahangir's Royal Animal

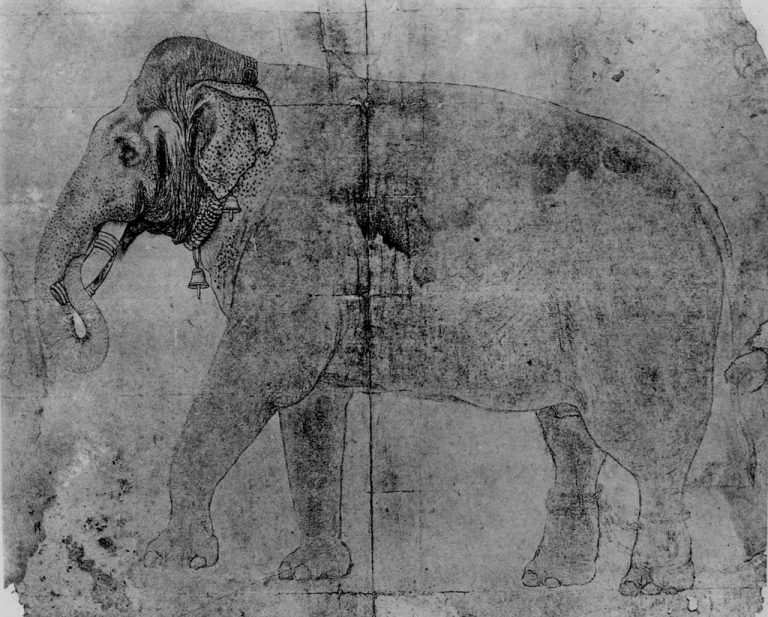

Jahangirnama is full of references to elephants, who were hunted, exchanged as gifts at the Mughal court, made to participate in fights with each other, and were seen in royal processions. Jahangir inherited his love for elephants from his predecessors: his great great-grandfather Babur, the founder of the Mughal empire, and his father, Akbar, who recorded adventures of the large mammal in their memoirs.

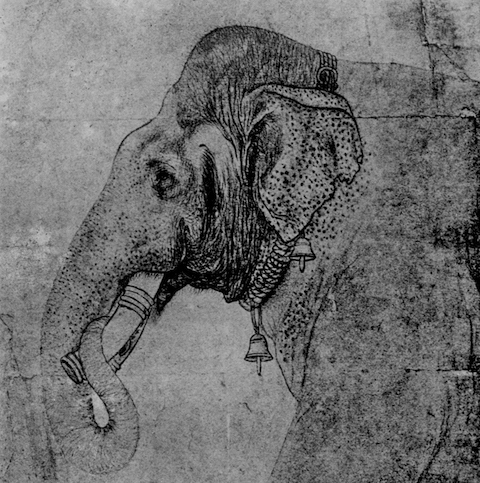

This drawing from the Museum of Fine Arts speaks of the great reverence that the elephant received during the Mughal period. Jahangir’s memoir shows that the animal commanded a high price and was included in the royal court, such as the imperial elephant Ratan Ganj. The work is one of the few known portraits of elephants executed during Jahangir’s period. The elephant occupies the entire composition, which makes it appear legendary or larger-than-life, a presentation that is quite true to its image in Mughal history.

The elephant is bejeweled around the tusk and the neck, which means that it may have belonged to the royal stable. Although the elephant is tied to a stake, its foreleg indicates movement, and an eagerness to move despite being tied down to a spot.

The portrait imparts a sense of vitality and rigour to the elephant, in line with Jahangir’s descriptions of the animal as a wild and difficult-to-tame creature. Of all the studies in the exhibition, the portrait stands apart because of its minimal use of colours, and the absence of a border.

Although the drawing has not been attributed to an artist, the application of ink suggests that the maker was adept at portraying an animal with realism. The carefully drawn outline of the elephant’s body speaks of the artist’s control of hand. The portrait emphasizes the animal’s flapping ears, the density of freckles around the face, and its long trunk that curls around the tusk.

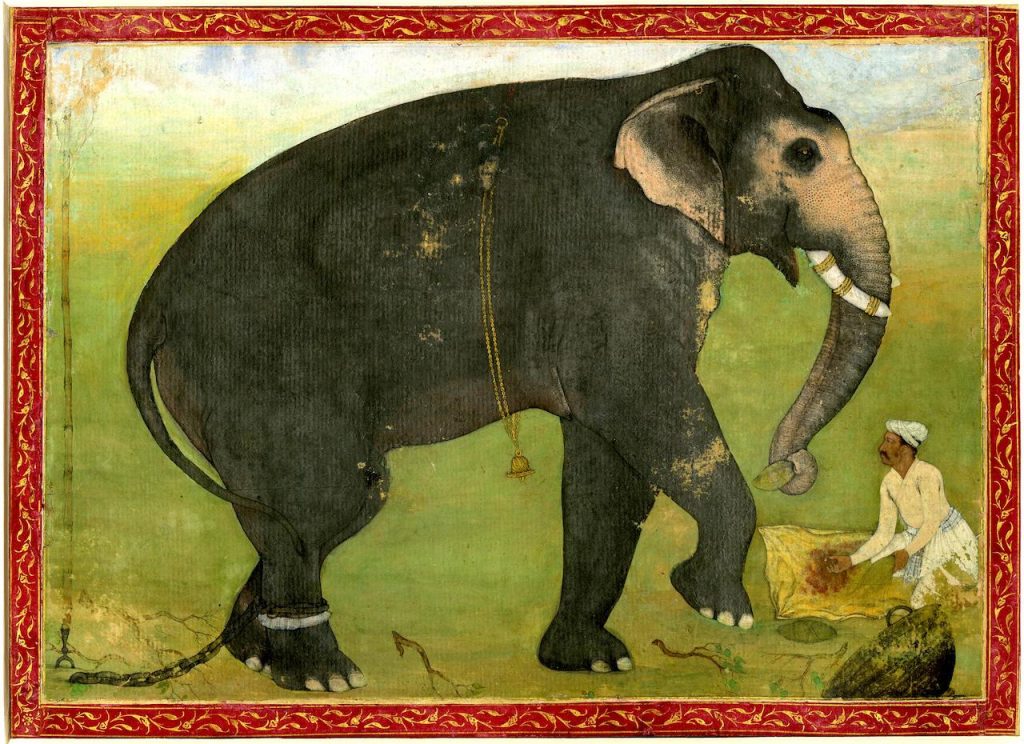

Compared to this portrait, another work from the Jahangir’s period enhances the elephant’s magnificence by portraying the royal animal’s body in deep green-blue tones. The elephant is portrayed against a bright green background, which is framed by a red floral border. The presence of the caretaker, or a mahout, recalls the attention given to the animal at the Mughal court. The elephant’s jeweled body looms large over the image, while the turbaned mahout is significantly smaller in size.

These portraits reflect the elephant’s prevalence in India history and culture, as seen in the image of the Hindu deity Ganesha, in religious festivals and pageants, and in battles led by kings since the ancient times. In the arts, the sculptures carved at the Mamallapuram group of monuments in Kerala, and on the walls of the Ajanta caves are examples of the iconic status of the elephant in Indian iconography.

Zebra - A Wild Ass

When Jahangir was presented a zebra for the first time, he found the animal “extremely strange” because its stripes resembled a tiger’s. Many thought that the zebra’s black and white stripes were unreal as it seemed to them that the patterns were painted on the animal’s body. Brought to India for the first time from Ethiopia in 1621, the zebra was presented as a rare gift to the Iranian emperor Shah Abbas I, with whom Jahangir often exchanged animals.

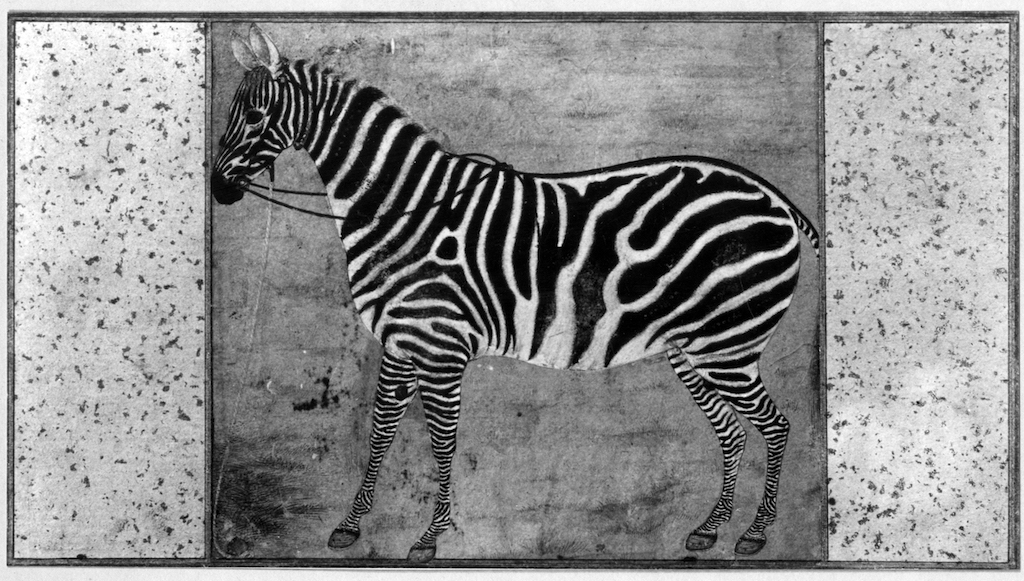

This work belongs to the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, and has been attributed to Mansur. The work is characteristic of the artist’s precise and realistic studies of the animal form. He has paid careful attention to painting the zebra’s stripes, which reflects Jahangir’s acute observation of the animal’s physical features. In comparison, the zebra’s muzzle has been portrayed with less detailing. The border has been painted over the zebra’s tail, and around its feet. The border also touches the ears, muzzle, and the stake to which the zebra is tied to. The presence of faint smudges in the background, especially in the bottom half of the work, indicate that an inscription would have been merged into the pale brown colour.

These observations point to the possibility that the work might have been re-worked. Yet, the work stands out for the zebra’s realistic portrayal. Another noteworthy feature of the work is its gold-sprinkled borders, a common form of margin decoration during Mughal period.

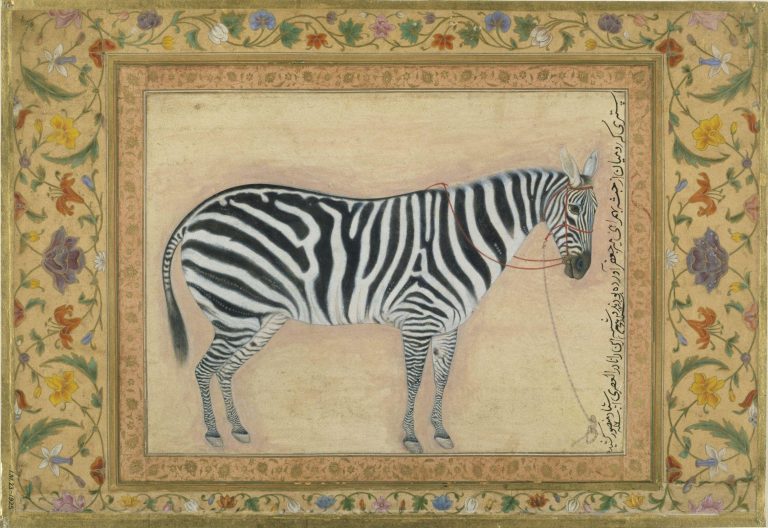

A more complete version of the zebra belongs to the collection of the Victoria and Albert (V&A) Museum, London. Executed around the same time as the MFA study, the stripes in the V&A work are more prominent. The muzzle has been more clearly depicted as the nostril is visible. Two stylized borders of floral patterns give ample room for the zebra’s portrait to stand out.

Seen alongside each other, both the works appear to be nearly identical in the portrayal of the zebra. The V&A work may have been the main one because of its perfectness in achieving a realistic and accurate depiction of the zebra. Jahangir’s inscription lends more value to the work as it was possibly the first study of the zebra commissioned by him. The previous study of the zebra, from the Museum of Fine Arts collection, might have been copied from the V&A work.

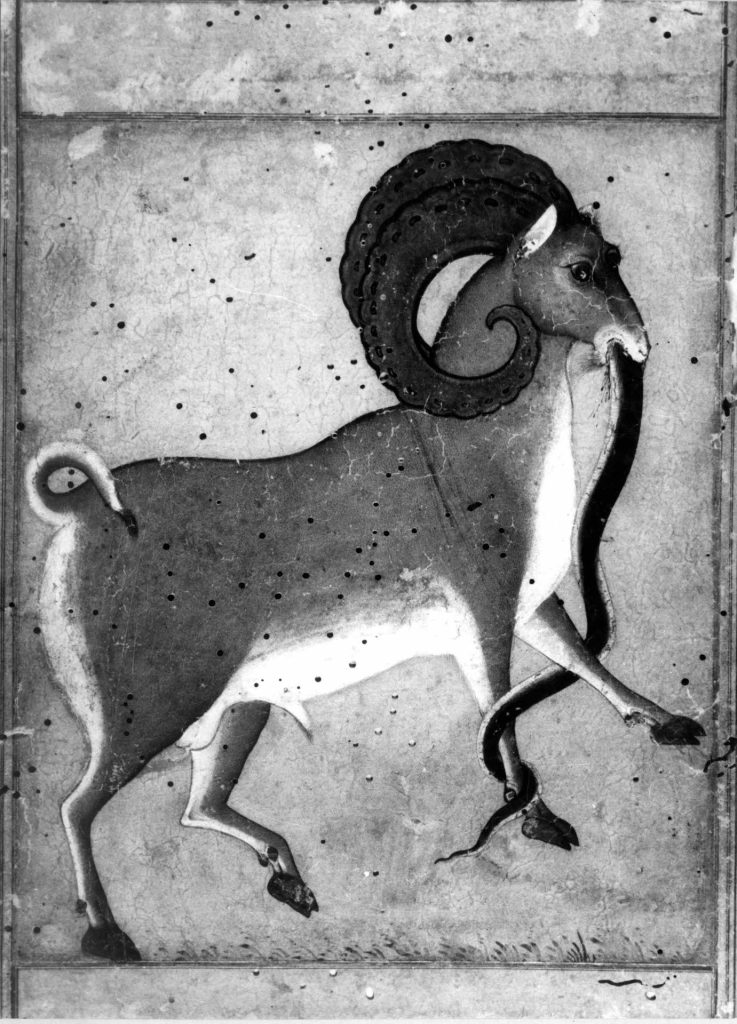

This study has been identified as “Markhor with a snake” from the collection of the Salar Jung Museum in Hyderabad. But the animal resembles a mouflon, a wild sheep with curved horns, and a brown-black body, with white underparts. The endangered animal is found in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cyprus, Iraq, Iran, and Turkey.

The work, executed in the early seventeenth century, has not been attributed to an artist. But the maker has achieved a great resemblance to the real animal by precisely depicting the mouflon’s large body. Special attention has been given to the sheep’s horns, which sharply curve from its head and end in a curl near its face. A pattern of dotted lines is visible on the horns, which have a coarse surface. The artist has attempted to show a sense of movement as the sheep swallows a snake. A closer look at the work reveals drops of blood falling from the mouflon’s mouth as a result of the sheep eating a snake. The movement suggests the sheep must have been leaping up from the ground to catch the snake, which is typical of the animal’s ferocity and masculine energy.

This is a male mouflon because it has large horns and a thin tuft of hair below the jaw. An unidentified script, likely in Persian, is inscribed at the bottom right corner of the work.

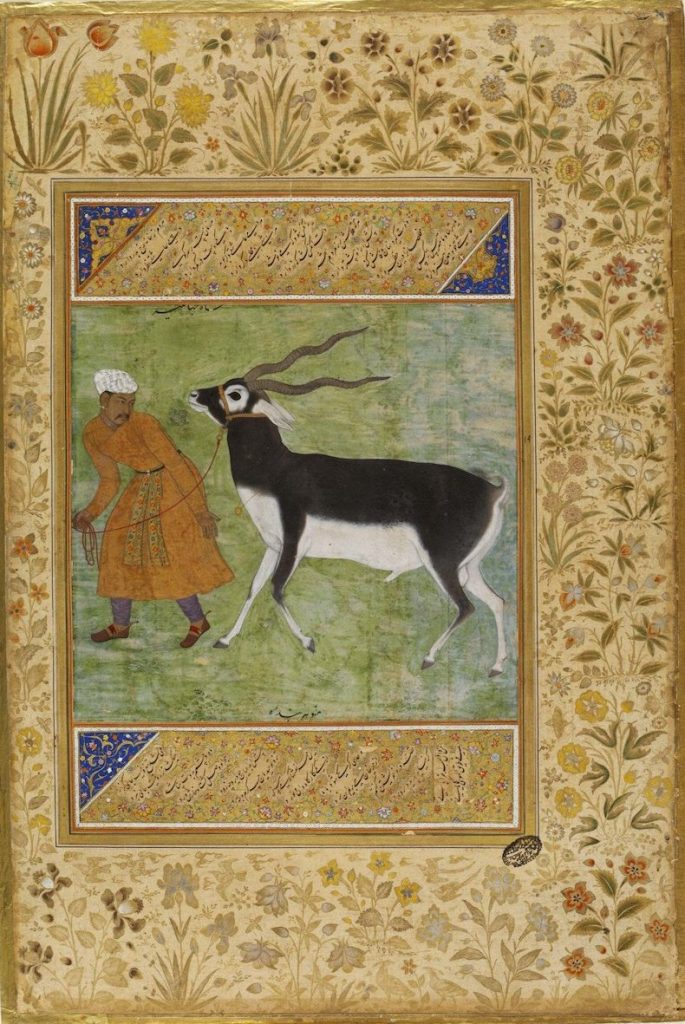

No similar work of the mouflon has been found so far. The closest we can get, in terms of style or visual language, is a work by Manohar, in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. The use of colour in the mouflon’s image has a resemblance to images of the blackbuck by the Mughal artist Manohar, who also worked in Jahangir’s studio. The darker shading of the goat’s upper body and white underparts in the blackbuck image recalls the portrayal of mouflon’s physical features. A sense of animated energy marks the blackbuck work, which is also present in mouflon’s image. The similarity in styles suggests the possibility of Manohar’s influence on the artist of the mouflon’s portrait.

Red roses, violets, and narcissi grow wild; there are fields after fields of all kinds of flowers in Kashmir - Jahangirnama

Narcissus is one of the many flowers mentioned by Jahangir from his travels in Kashmir, which he referred to as a “perennial garden.” According to the emperor, Ustad Mansur drew more than a hundred pictures of the Kashmir flowers, but only a handful of his works are known. Most notable among them is a painting of tulips with a butterfly and a dragonfly hovering over the flowers.

Besides Mansur, Mohammad Nadir of Samarkand was the other seventeenth-century Mughal painter of flower studies. His portrait of a yellow narcissus gives an indication of the style adopted by the two artists in their flower portraits. Executed in the 1620s, a period that coincided with Jahangir’s Kashmir visit, the work presents a frontal view of the narcissus. A stalk rises above the ground, and its leaves swirl around the stem in gentle movements. The artist has also emphasized the iridescent orange of the petals, which are also in a state of movement. The sharp curves of the leaves and the petals indicate that the flower may have been wilting when it was viewed by the artist.

What is absent in the narcissus’ image is the corona, the flower’s central part that nestles between the petals like a crown. The narcissus’ swirling leaves and petals indicate wild growth, corresponding to Jahangir’s sighting of the flower in the gardens of Kashmir, along with roses, violets, tulips, and jasmine. The hovering butterfly creates an illusion of depth and space around the narcissus, which is painted over a bright orange reminiscent of twilight.

The focus on movement, growth, and botanical details in the Mughal flower studies has been compared with illustrations of plants in European scientific books. The image also shows a clear influence of Mansur’s paintings in which butterflies, birds, and insects are seen fluttering over the flowers.

Sights and Sounds from the Natural World

Sound credit of white-throated kingfisher’s call: Ramit Singal / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML86078991)

The birds in Jahangiri folios either give a faint suggestion of their habitat or remove the natural surroundings completely. In the end, we share pictures and sounds of the birds represented in the Mughal paintings, with the intention of looking at the natural world through the animal’s subjectivity. The material, from the collection of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, USA, shows the birds in their natural habitat, and includes sounds clips of bird calls. As you will see, the hyperlinked information below makes the birds come alive in ways different from the Jahangir folios.

Gyrfalcon Mallard Duck Lesser Flamingo

White-throated kingfisher Indian pitta

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank the team of Center for Art and Archaeology for their guidance and support to realise the project: Dr. Vandana Sinha, Director; Sushil Sharma, Assistant Director; Stuti Gandhi, Senior Research Associate, and Sayed Ehtesham Rizvi, Librarian, among other members of CA&A. This project would have not been possible without the mentorship of Prof. Nuzhat Kazmi, Head of Department, Art History and Art Appreciation, Jamia Milia Islamia University, New Delhi.

Curator’s Bio

Ankush Arora is a graduate student in the M.A. Art History program at Syracuse University, New York state, USA. His research interests focus on artistic representations of humans and nonhumans from an interdisciplinary perspective. Prior to graduate school, Ankush worked as an arts journalist and gallery manager in New Delhi, and published articles and essays on modern and contemporary South Asian art. He received a degree in B.A. (Hons.) English from Hindu College, University of Delhi, and a post-graduate diploma in journalism from the Indian Institute of Mass Communication, New Delhi. On Instagram, he posts as @_muraqqa_.