Vaishnavi Kambadur

Human hair and its long history in India and South Asia are often taken for granted. Taking paintings and photographs as a starting point, in We, All Share the Same Hair, you can:

※ Learn about popular myths, legends, cultural and political events through human hair.

※ Explore artworks that question our long-held habits, beliefs, and perceptions of hair practices.

※ Analyze artists and their interpretation of people who share a close yet unspoken relationship with their hair.

Hair — An Extension of Our Bodies?

We encounter hair every day — it is one of the most intimate parts of our body. Although we groom, display, protect, collect, and discard it, the presence or absence of hair offers us many choices. However, are these choices given to everyone? Are they bound by cultural and social norms? Do they inform how we identify ourselves and our bodies?

T.S. Satyan, Untitled, late 20th century, Silver gelatin print, Gifted by the TS Satyan Family Trust, Courtesy of the Museum of Art & Photography, Bengaluru, PHY.10344

The stage between oiling and braiding hair is rarely captured. In some cultures of South Asia, long, black and thick hair is associated with youth, hygiene and, modesty. Typically, mothers oil their child’s hair to nourish, preserve and, nurture it.

T.S. Satyan photographs a young girl with black, wavy hair that almost covers half of her body. T.S. Satyan was a photojournalist for newspapers and magazines. He grew up in a family with 14 siblings. The seriousness of his photographs can be seen in his documentation of children in South Asia particularly when he exhibited at the United Nations headquarters in New York City during the only International Year of the Child (1979).

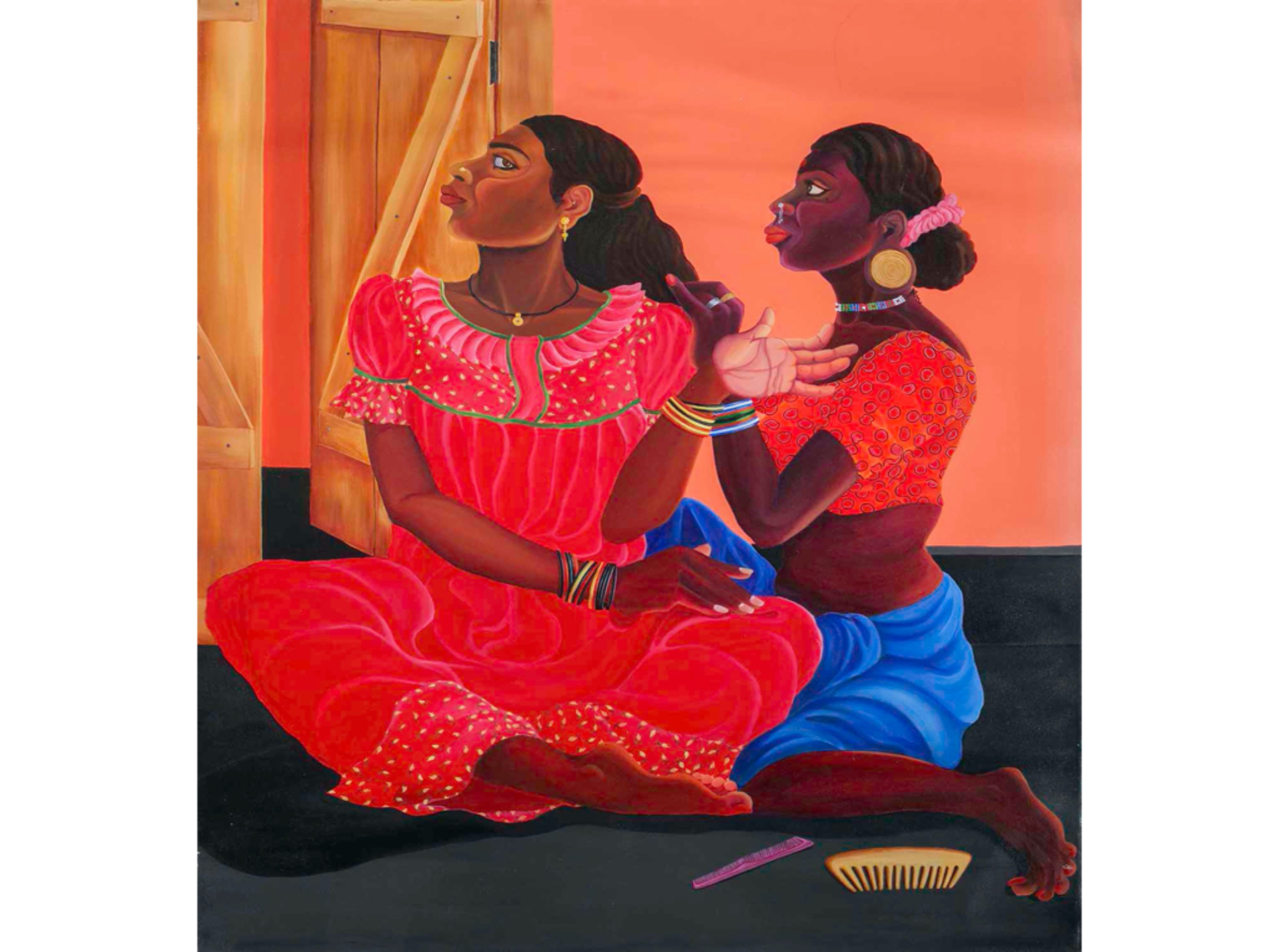

Sunil Laal T.R., Mid-day, 2008, Acrylic on canvas, Courtesy of the Museum of Art & Photography, Bengaluru, MAC.01537.

Grooming of hair is a personal experience that women entrust women to fulfill. In India, ‘mid-days’ entail women grooming each other’s hair, making this routine practice sacred and special.

Hair nurtures a bond between humans. The artist Sunil Laal T.R. uses painting to shed light on the Paniyar communities in Kerala. He fulfills his responsibility to society by presenting the changing lives of indigenous people. In addition, here, he explores how the grooming of hair influences the movement of a person’s body.

Details of Mid-day

This elaborate depiction of hair rituals, in which one person’s hair is bound in a bun while another person’s hair is in half knot, illustrates the many ways in which women wear their hair. Also, we can see various styles of combs on the floor, a comb for wet hair and a fine toothed one for parting hair.

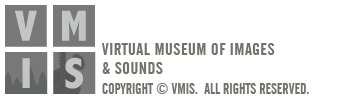

Krishna Adorning Radha’s Hair, ca. 1815-20, India, Punjab Hills, Kangra region Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection, Gift of Paul Mellon, Courtesy of Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 68.8.82

Hair grooming also engages with playfulness and sensuality. In this painting, we see the prince Krishna with his long hair controlled with a peacock-headed crown, and Radha, the princess whose long hair merges with her embroidered headcover.

Notice how Krishna’s hand almost caresses Radha’s flowing and lightly braided hair with a beautiful string of pearls. The play of hair in spaces like forests, gardens, and palaces portrays Krishna and Radha’s many moods like sorrow, jealousy, and joy. The Kangra artist depicts Radha’s “raven-like” long black hair in the same tone as her embroidered headcover while concealing and revealing the princess’s hair.

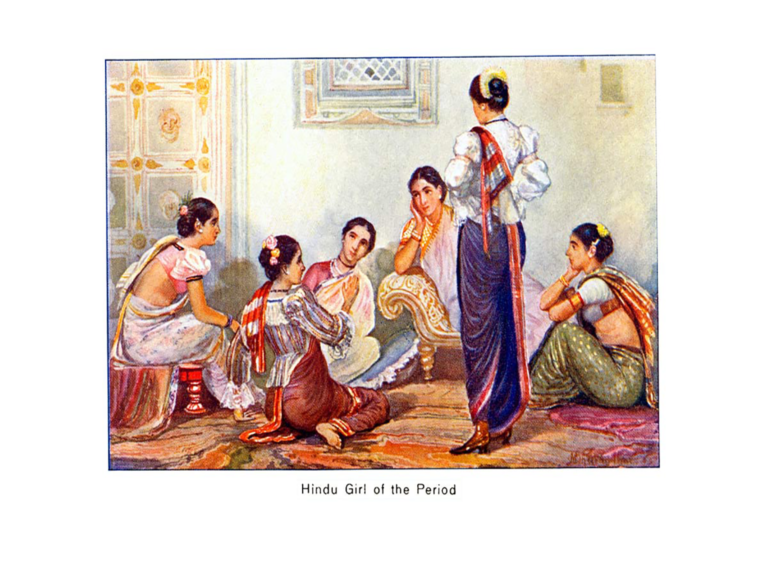

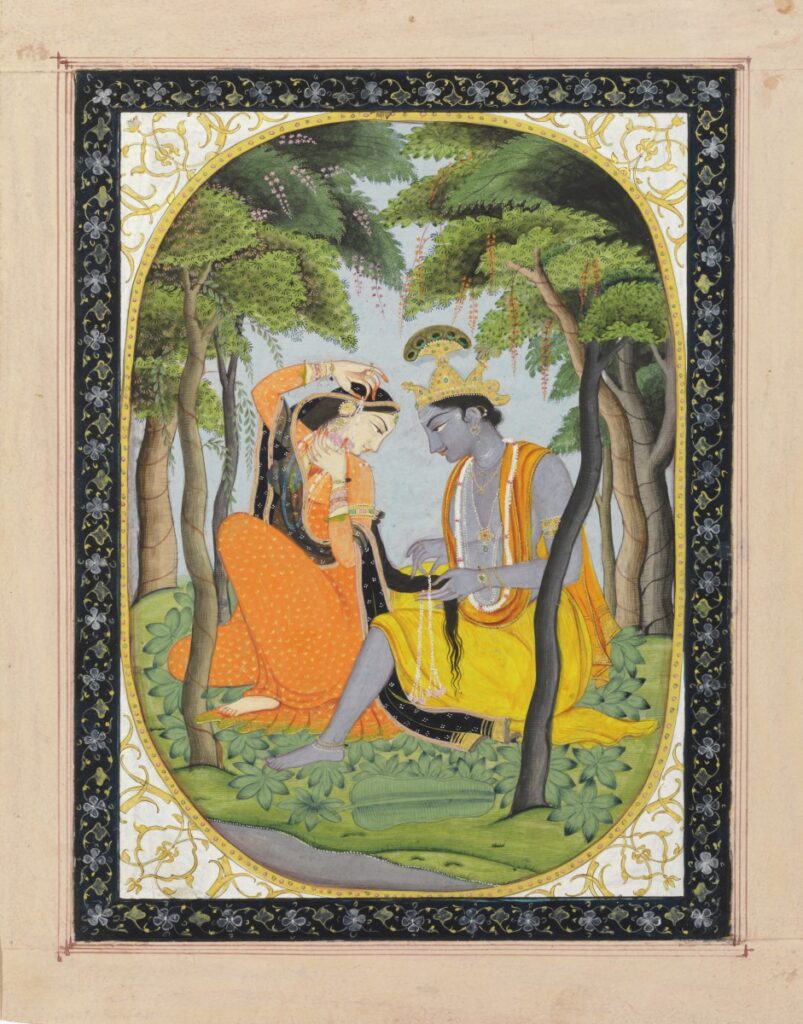

Draupadi Vastraharan, 19th century, 1898, India, Ravi Varma Press, Oleograph, From the Collection of Hemamalini and Ganesh Shivaswamy – The Ganesh Shivaswamy Foundation, Bengaluru

Touching or pulling of hair is not always consensual. In the popular Hindu legend Mahabharata, the central character Draupadi lets down her hair to show the humiliation she feels when her five husbands gamble away her sanctity in a game of dice. Her courageous act defies cultural modesty and provokes Dusshasana to pull her hair in public.

In folk legends of Tamil cults, Draupadi is worshipped for her loose hair, that secretly symbolizes menstruation. Even today, many women leave their hair unwashed to follow this unsaid routine. Think about a time when you knowingly or unknowingly used hair to express something to people around you.

Unveiling Hair’s Potential

Hair is powerful when its potential is challenged across centuries. Can hair act as armor for our body? Do control and lack of hair have different social meanings? What is the role of adornment in hair practices?

Thota Vaikuntam, Untitled, Watercolor on paper, Courtesy of the Museum of Art & Photography, Bengaluru, MAC.02902

In India and South Asia, hair is typically tamed and controlled using hair accessories. Although the accessories look aesthetically appealing, their function is to ensure that hair stays in its place.

Artist Thota Vaikuntham paints the lives of people around him and is particularly inspired by his mother. Most of the women in his paintings have their hair in a bun, adorned by fragrant jasmine flowers and gold jewelry.

Goddess with Weapons in Her Hair, 2nd century B.C., North India, Copper alloy, Samuel Eilenberg Collection, Gift of Samuel Eilenberg, in honor of Steven Kossak, 1987, Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987.142.289

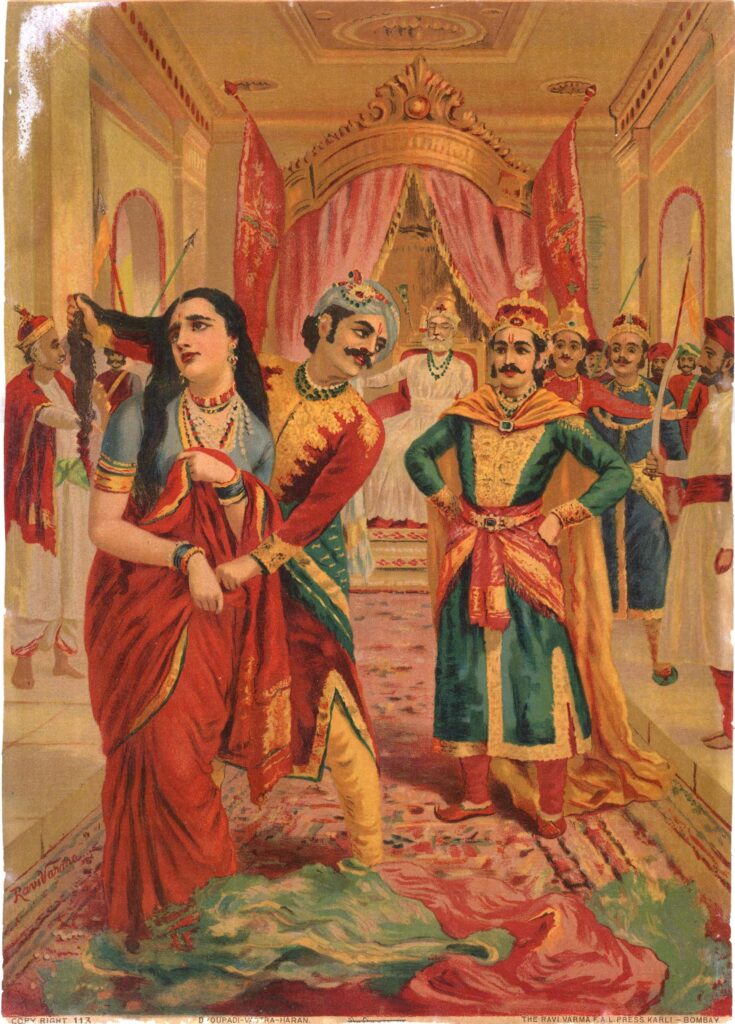

Jayashree Chakravarty, Untitled, 1992, India, Oil on canvas Courtesy of the Museum of Art & Photography, Bengaluru, MAC.00619

Goddess with Blue Hair

Untamed Hair can uncover unseen meanings. Even though the artwork (on the left) represents goddess Durga, her blue hair and pose (lalitasana) indicate that she might be god Shiva, the protector of the earth. Click here to read about Shiva’s powerful locks in The Descent of Ganga or Gangavataran.

Goddess with Weapons in her Hair

Untamed hair is often feared; we see this in this goddess from the 2nd century BC. Isn’t it fascinating that arrows and axes are radiating from hair? This mysterious figure, an early goddess, teaches us that women are powerful and can control their choices.

We often use our bodies to shield ourselves. Did you ever wonder about using hair, also a part of our bodies, as a shield?

Anoli Perera, I Let My Hair Loose: Protest Series, 2010, Sri Lanka, Photo Print, From the Collection of Anushri Jain and Amit Kumar Jain, Courtesy of the Museum of Art & Photography, Bengaluru, PHY.12126 to PHY.12130, Click on the images for more details

Hair has endless functions. In Sri Lanka, artist Anoli Perera creates photo-performances inspired by her childhood memories. She recalls old photographs in her grandmother’s home and how the women in these photographs show no emotion. Unlike the women in the old photographs, women in the photo-performances defy us from viewing their faces. Instead, we uncover layers of hair in every direction. These layers of hair have layers of meanings that manifest in the form of protest. Read more here.

What is real hair? Who owns this hair? The hair Perera uses is not her own, but someone else’s – it is a wig made of donated or collected hair.

Deepa Mehta on Water (2005), Courtesy of TIFF Originals, Published in 2017, Click on the image to watch the video

Donating hair is not always a personal choice. In the early 19th century, when child marriage was still practiced, widowed girls would be sent to a home in Banaras, on the banks of river Ganges. They would be stripped of any colorful belongings and their heads would be shaved.

Widowed women didn’t have rights to any worldly pleasures — they were forced to renounce their life along with their hair. Click here (Widows, Education and Social Change in Twentieth Century Banaras, 1991) to understand how these rituals changed over time.

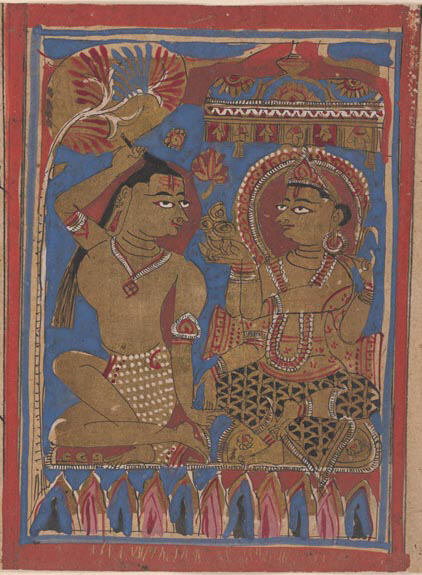

Mahavira Plucks Out His Hair, Detail of Folio from a Kalpasutra Manuscript 15th century, India, Gujarat, Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, Rogers Fund, 1955, Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 55.121.38.17

In Jainism, Mahavira’s pulling his hair was an important ritual of renunciation. Sitting below an Asoka tree in a forest, pulling out clumps of hair initiated his life as an ascetic, leaving behind all the human desires. This hair is carefully collected and preserved to ascertain his new life.

This manuscript from the 15th century teaches us that plucking and preserving hair was an important ritual in Jainism and early Buddhism. Notice how calm Mahavira’s face is while he endures the intense pain. The god next to Mahavira, Kuvera, places his hands forward to collect the sacred hair.

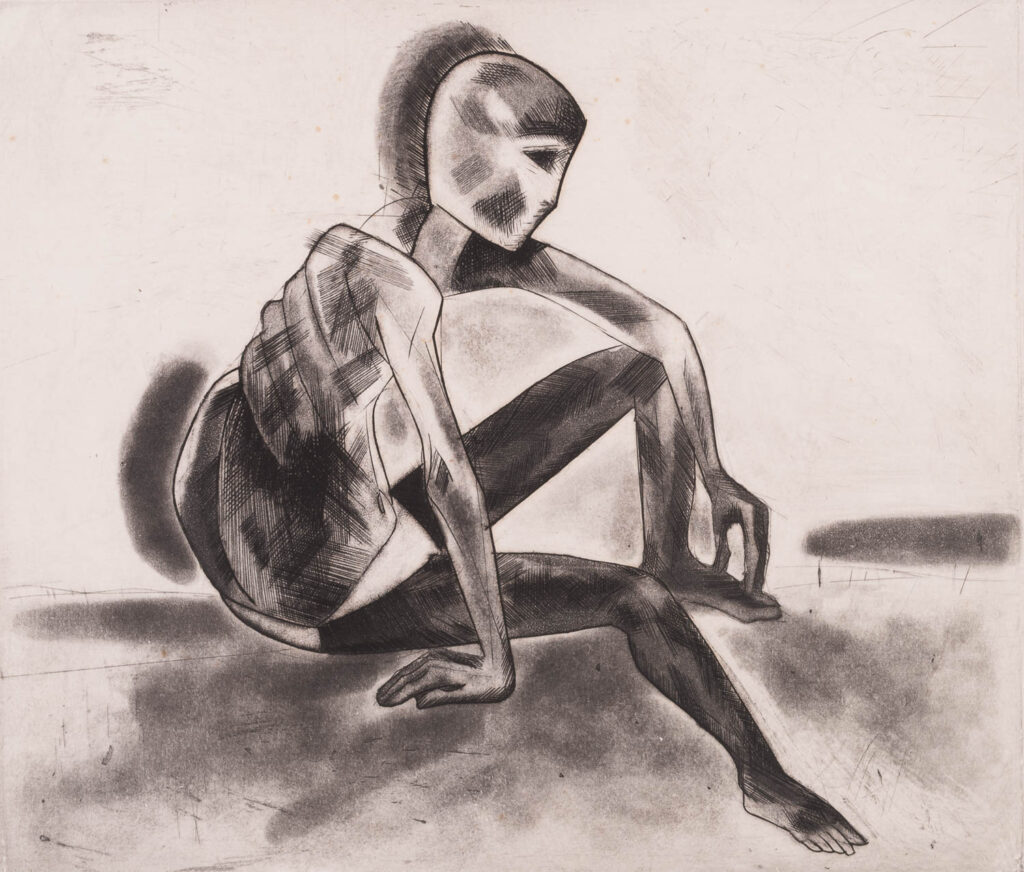

Somnath Hore, Untitled, 1978, Etching, Courtesy of the Museum of Art & Photography, Bengaluru, MAC.01995

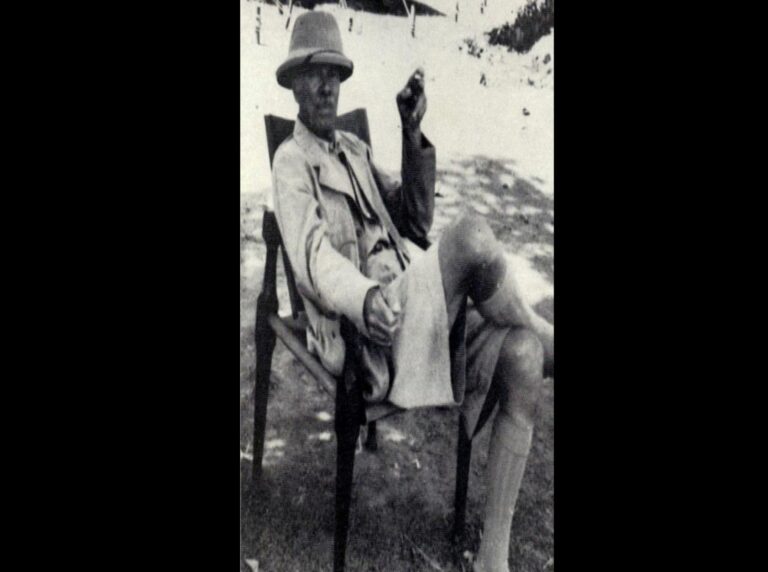

Shaving rituals are common in South Asia — they are often practiced after the death of a family member or during the birth of a baby. Conversely, the loss of hair because of illness and poverty is rarely discussed.

Somnath Hore depicts a person from his memories of the Bengal famine of 1943, an unfortunate and painful event in the mid-20th century. The lack of hair on the figure’s head, body, and face indicates the powerlessness of those marginalized by the famine.

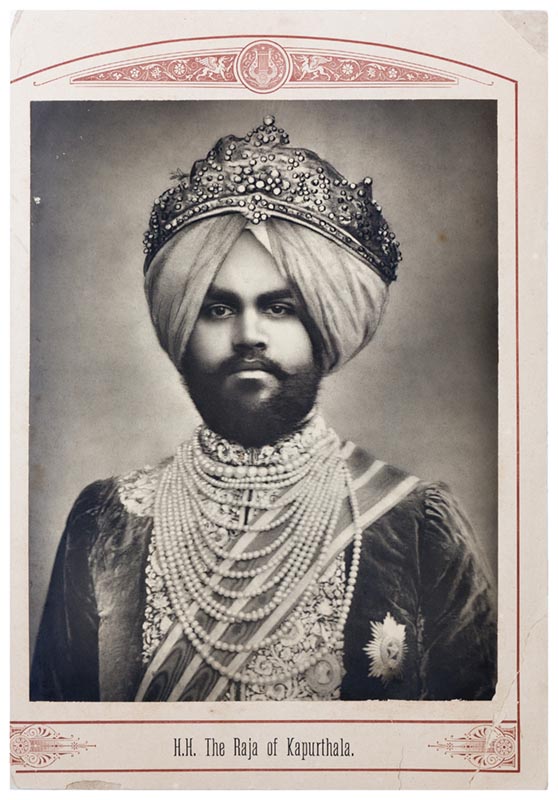

Lala Deen Dayal, H.H. The Raja of Kapurthala, 18th century, India, Albumen print, Courtesy of the Museum of Art & Photography, Bengaluru, PHY.00086

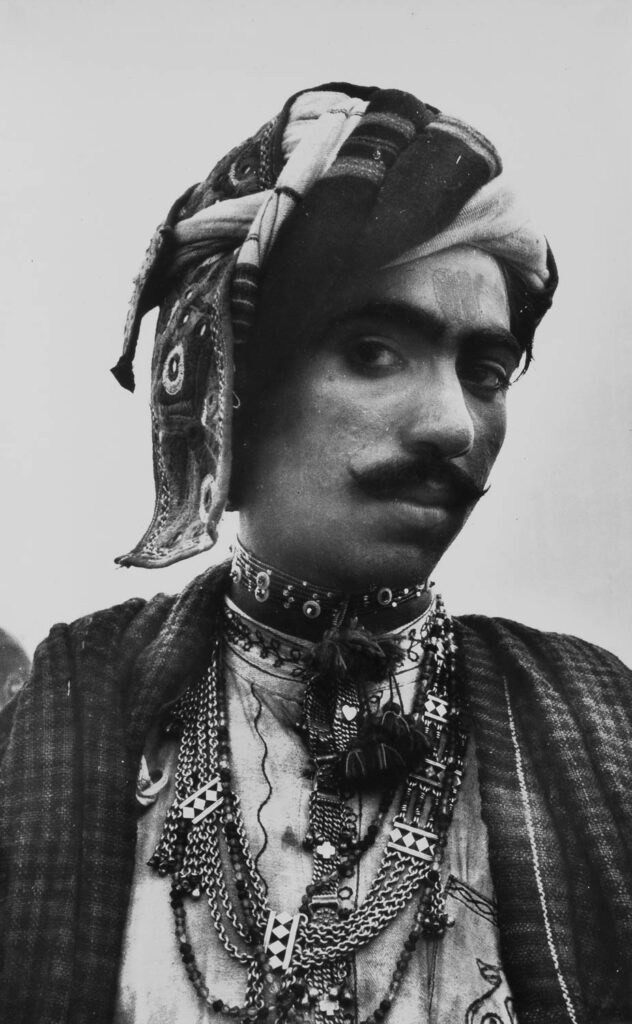

Jyoti Bhatt, ‘Rabari’, 1958, India, Gujarat, Saurashtra, Silver gelatin print, Courtesy of the Museum of Art & Photography, Bengaluru, PHY.06902

Hair grows and falls; it lives a life of its’ own. Hair accessories are equally powerful.

Here we see aspects of control in the form of a draped turban, we also see the eyebrows and moustache groomed upward, indicating the man’s masculinity.

The Turban with a Crown

H.H. The Raja of Kapurthala’s portrait shows us that turbans not only highlight a person’s religious identity but also present as a visible marker of power. Watch more about his reign here.

The Turban with Rabari Embroidery

The portrait documented by Jyoti Bhatt expresses how the pastoral and shepherd Rabaris of Gujarat dress. The intricate mirror embroidery on the draped turban and jewelry indicate his community’s identity. Read more about his work in Gujarat here.

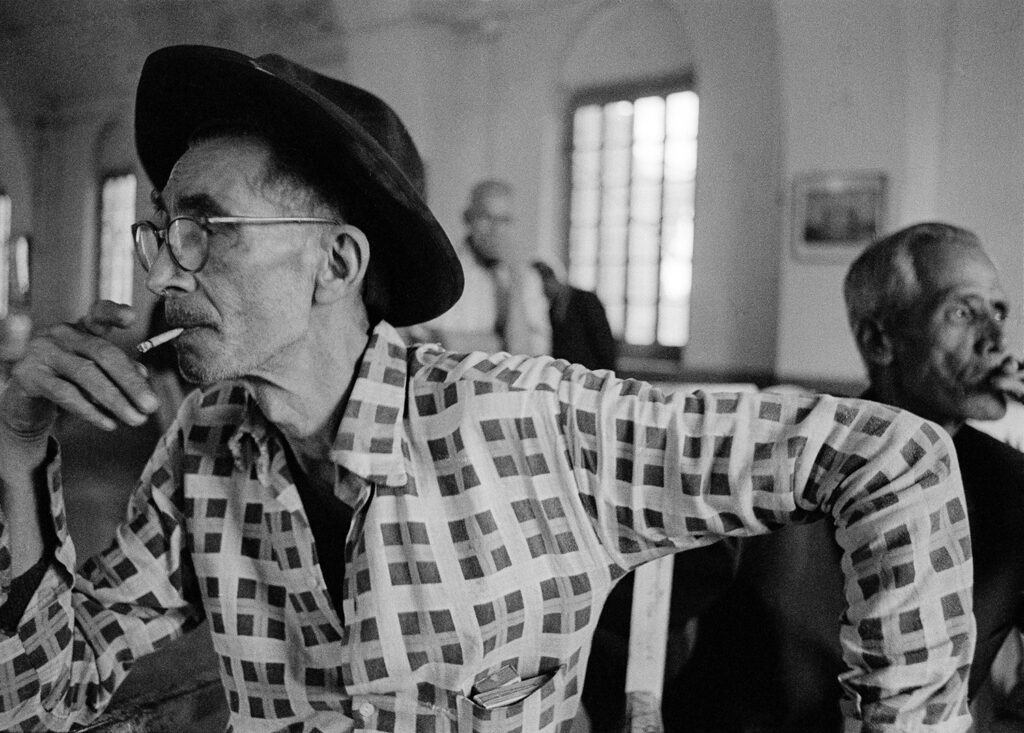

Mr. Carpenter, 1981, Tollygunge, Calcutta, Karan Kapoor, Silver gelatin print, Gift of Karan Kapoor, Courtesy of the Museum of Art & Photography, Bengaluru, PHY.07557

Karan Kapoor documents the disappearing nostalgia of hats, tiaras, and colonial styles by capturing Mr. Carpenter in a home for the elderly in Tollygunge, Calcutta. The photographer records their ways of life inherited from both British and Indian origins.

The Homburg Hat finds its origins in Saarland, Germany. Known as the Eden hat in Saville Row, London, the hat might have arrived in India with the East India Company. Do you think fashioning hair is nostalgic?

Does Hair Create or Destroy Barriers?

Hair exchanges many hands in the form of talismans and wigs. In this exchange, hair, in artistic practice, questions long-held cultural barriers.

Sheela Gowda, Behold, 2009, Purchased with funds provided by the South Asia Acquisitions Committee 2014, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T14118, Courtesy, and Copyright: (c) Sheela Gowda / Photo (c) Tate, Sheela Gowda – ‘Art Is About How You Look At Things’ | Tate Shots

This installation, Behold, highlights the “control and vulnerability” of human hair outside the body. The artist Sheela Gowda explores the origins of these talismans, which she notices on her trips to the streets of Bengaluru.

Sheela Gowda’s process of translating hair in a museum space presents a new way to view it as an artistic medium — to be manipulated after it detaches from the body. The braided natural fiber resembles knotted cotton yarns.

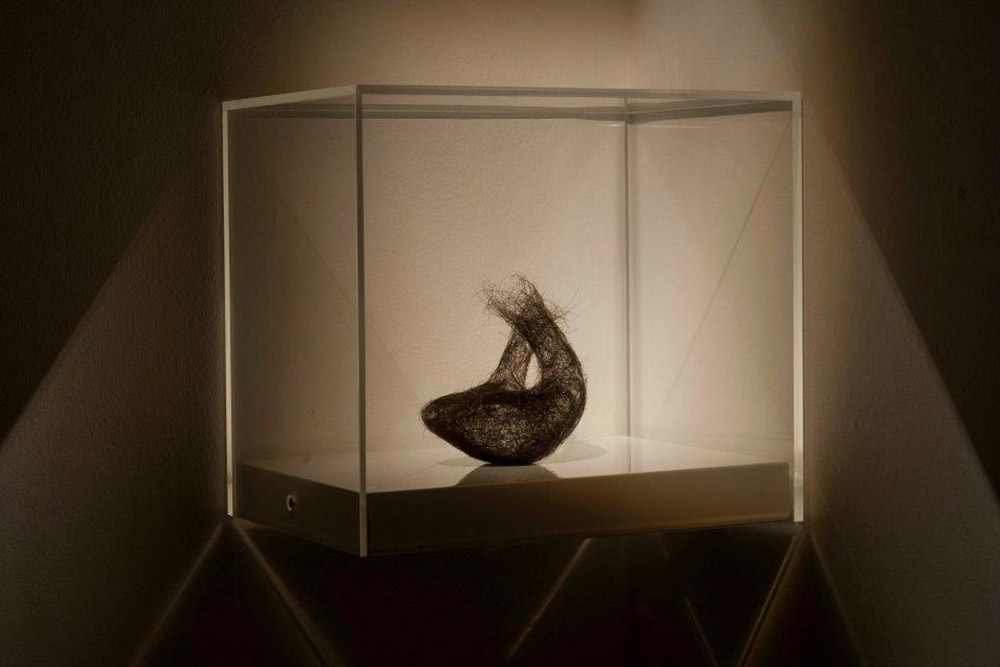

Ali Kazim, Untitled Heart, 2010, Pakistan, human hair, hair spray, Perspex box, Courtesy of Ali Kazim

We trust hairstylists and barbers to cut our hair. Similarly, in many parts of South Asia like Pakistan, people sell or donate their hair to traders who go door to door in search of hair. This hair is then sent to many parts of the world to make wigs. The artist Ali Kazim explores the process of collecting hair as a starting point to expose many layers of what it means to create art today.

Hair evokes many feelings; it can be disgusting and yet attractive. Ali Kazim merges these expressions in his hair sculptures. Kazim turns the human heart inside out with a perfectly placed web of interlaced textures. Do hints of transparency and opaqueness in this hair sculpture help you relate to your own body?

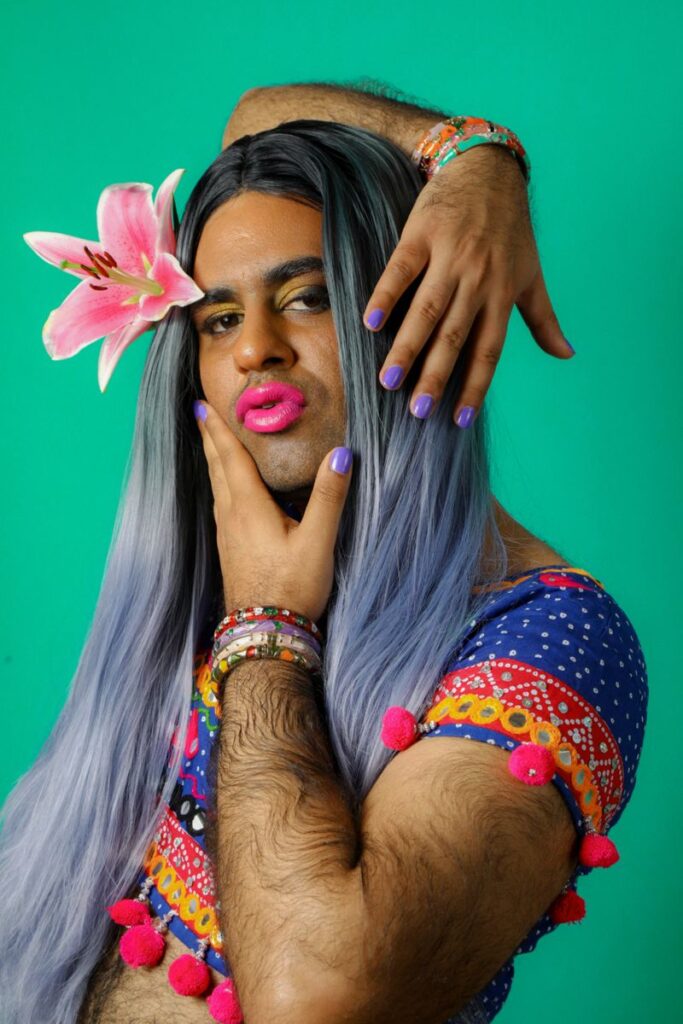

Hair challenges cultural anxieties. Alok V Menon and Brian Vu use photography to shed light on the issues around society’s perception of hair. Who gets to control how much hair is visible on our body?

Alok V Menon states that, “When I told my family, I was trans, one of their initial reactions was, ‘But you’re so hairy! It’s going to be so difficult to remove all your hair to be a woman, so you should just give up.’ They were zeroing in on my body hair as the barrier for me to be seen as feminine. (trans body hair — ALOK)“

Ketaki Sheth, Yesha and Niddhi, 1998, Silver gelatin print, Courtesy of Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru and Ketaki Sheth, PHY.01784

We saw that hair can be used to express human emotions. These emotions are negotiated in the form of hair exchanges from close friends to strangers. If you look closely, every artist in this exhibition works with personal memories to communicate their relationship with hair.

Hair has always held a special place for me. Leaving my hair loose on a Sunday afternoon after a hair wash has been one of my fondest memories.

Bibliography

Balakrishnan, Usha. “The Nizam’s Jewels | Treasures of India”. Live History India, December 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DgdvUTDyzB4.

Chong, Elaine, and Menon, Alok V. “’ Perhaps life would be easier if I shaved, but why?’,” BBC. 22 May 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-48149985.

Hiltebeitel, Alf, and Barbara D. Miller. Hair: Its Power and Meaning in Asian Cultures. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998.

Kumar, Vijeta. “Wild Hair and Mad Dalit Women.” Rum Lola Rum, 14 April 2018. https://www.firstpost.com/long-reads/of-wild-hair-and-mad-dalit-women-4433381.html.

Sheth, Ketaki. Twinspotting: Photographs of Patel Twins in Britain and India. Stockport, England: Dewi Lewis, 2000.

Tarlo, Emma. Entanglement: The Secret Lives of Hair. London: Oneworld, 2017.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Alani Gaunt and Yael Bame for proof-reading the content of the exhibition. I also thank Deborah Strauss and Dr. Arnika Ahldag for reviewing the exhibition storyline and sharing their personal experiences with hair. The exhibition wouldn’t look the same without Vineesh Amin’s meticulous feedback on the layout.

I am grateful to the AIIS team for their technical guidance throughout the workshop. I would also like to offer thanks to all the artists, museums, and institutions who provided open access to their collections. I would like to particularly thank the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), Bengaluru; my co-workers Amelia Droza and Priya Latha for sharing the gift documents; Rucha Vibhute for providing the cataloging information, and Prachi Gupta for her invaluable knowledge of MAP’s photography collection.

Special thanks to Dr. Madhuvanti Ghose for her encouraging words and exceptional curatorial advice.

Featured Image: Sunil Laal T.R., Mid-day, 2008, Acrylic on canvas, Courtesy of the Museum of Art & Photography, Bengaluru, MAC.01537.

Accessibility: Color access tool, Courtesy of http://colorsafe.co/, and Color Contrast Analyzer

©We All Share the Same Hair; Vaishnavi Kambadur is an Assistant Curator at the Museum of Art & Photography, Bengaluru. She conducts research related to the craft collection, permanent exhibitions, and special exhibitions. Kambadur holds a MA in Fashion Studies from Parsons School of Design, The New School, New York, and a Bachelor’s degree in Knitwear Design from the National Institute of Fashion Technology, New Delhi.